W ß

■

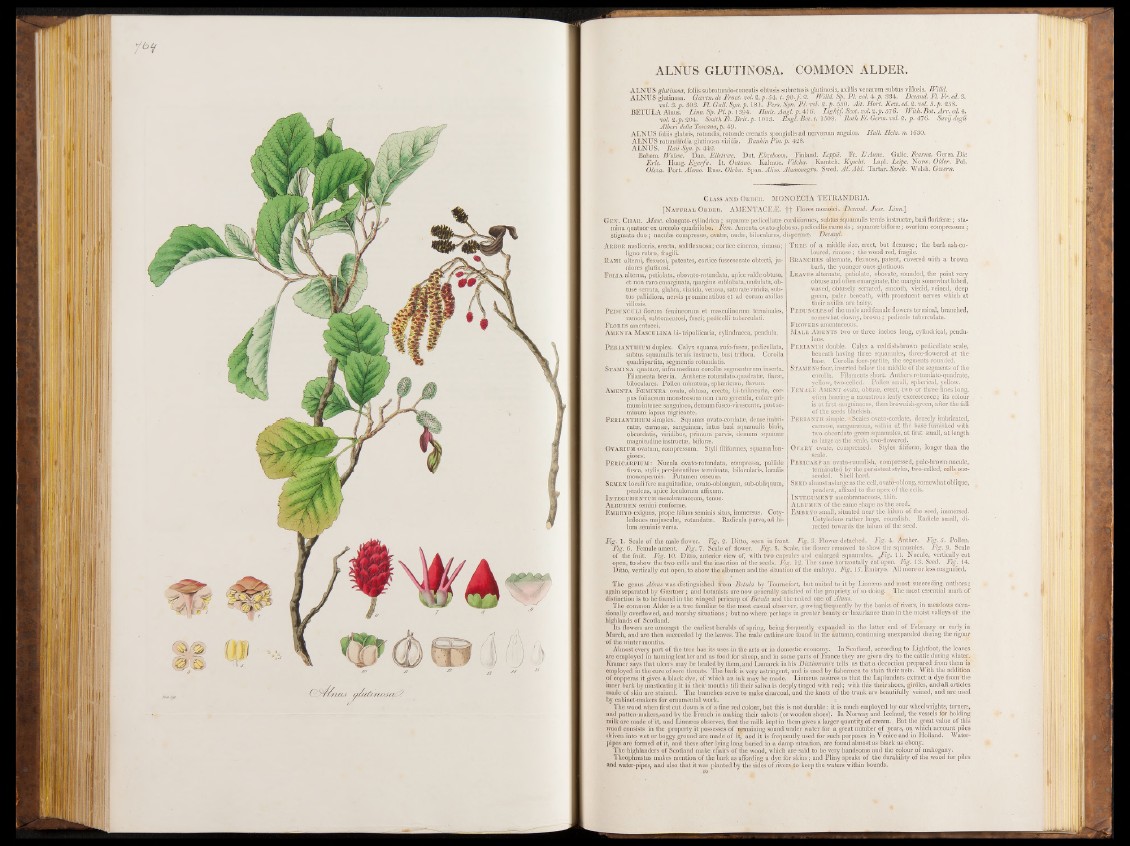

ALNÜS GLUTINOSA. COMMON ALDER,

ALNUS glutinosa, foliis subrotundo-cuneatis obtusis subretusis glutinosis, axillis venarum subtus villosis. fVilld.

ALNUS glutinosa. G a r tn . de Fruct. vol. 2. p.54t. t. 90. /■ 2. IVilld. Sp. PL vol. 4. p. 334. Decand. Fl. F r. ed. 3>

m l 3. p. 803. Fl. G'all. Syn. p. 181. Pers. Syn. PI. vol. 2. p. 550. A it. Hort. Kern. ed. 2. ml. 5.p. 258.

BETULA Ainus. Linn. Sp. PI. p. 1394. Huds. Angl. p. 4 J 6. Lig h t/. Scot. vol. 2 .p. 576. W ith . Bot. A rr. ed. 4.

vol. 2 2 0 4 . Smith Fl. B r it. p. 1013. Engl. Bot. t. 1508. ' Roth Fl. Germ. vol. 2. p. 476. Savij degli

Alberi della Tóscana^p. 4@. _

ALNUS foliis glabris, rotundis, rotunde crenatis spongiolis ad nervorum angulos. Hall. Helv. n. 1630.

ALNUS rotundifolia glutinosa viridis. Bauhin Pin. p. 428.

ALNUS. R a iiS y n .p . 442. _ f .

Bohem. Wolsse. Dan. Elletrae. Dut. Ebzeboom. Finland. Leppa. Fr. L ’Aune. Galic. Feama. Germ. Hie

Erle. Hung. Egerfa. It. Oniano. Kalmuc. Vilcha. Kamtch. Kyscht. Lapl. Leipe. Norw. Older. Pol.

Olszcty. Port. Alemo. Russ. Olcha. Span. Aliso. Alamonegro. Swed. Al. A hl. Tartar. Serek. Welsh. Gztiern■>

Class and Order. MONOECIA T E TRANDRIA.

[N atural Order. AMENTACEÆ. f t Flores’ monoicn Hecand. Juss. Linn.']

Gen. Ciiar. Masc. elongato-cylindrica ; squamæ pedicellate cordiformes, subtus squamulis ternisinstructæ, basi floriferæ ; stamina

quatuor ex urceolo quadrilobo. Fern. Amenta ovato-globosa, pedicellis famosis ; squama bifloras ; ovarium compressum ;

stigmata duo ; nuculæ compressas, ovatæ, nudæ, biloculares,‘dispersas. Hecand.

Arbor mediocris, erecta, sedflexuosa; cortice cinereo, rirnoso;

ligno rubro, fragili.

Rami alterni, ftexuosi, patentes, corlice fuscescente obtecti, juniores

glutinosi.

Folia alterna, petiolata, obovato-rotundata, apice valde obtusa,

et non raro emarginata, ipargine sublobata, undulata, ob-

" tuse serrata, glabra, viscida, venosa, saturate viridia, sub-

tiis pallidiora, nervis prominenlibus et ad eorum axillas

villosis.

Pedunculi florum femineorum et masculinorum terminales,

ramosi, subtomentosi, fusci ; pedicelli tuberculati.

Flores amentacei.

Amenta Masculina bi-tripollicaria, cylindracea, pendula.

Perianthium duplex. Calyx squama rufo-fusca, pedicellata,

subtus squamulis ternis inslructa, basi triflora. Corolla

quadripartita, segmentis rotundatis.

Stamina quatuor, infra medium corollas segmentorum inserta.

Filamenta brévia- Antheræ rotundato-quadratæ, flavæ,

biloculares. Pollen minutum, sphæricum, flavum.

Amenta Foeminea ovata, obtusa, erecta, bi-trilinearia, corpus

foliaceum monstrosum non raro gerentia, colore pri-

mum intense sanguineo, demum fusco-virescente, post se-

minum lapsus nigricante.

PERIANTHIUM simplex. Squamæ ovato-cordatæ, dense imbricate,

carnosæ, sanguineæ, intus basi squamulis binis,

obcordatis, viridibus, primum parvis, demum squamæ

magnitudineinstructæ, bifloræ.

Ovarium ovatum, compressum. Styli filiformes, squama lon-

giores:

P èRICARPIUM : Nucula ovato-rotundata, compressa, pallide

fusca, stylis persistentibus terminata, bilocularis, loculis

monos permis. Putamen osseum.

Semen loculi fere magnitudine, ovato-oblongum, sub-obliquum,

pendens, apice loculorum affixum.

Integumentüm membranaceum, tenue.

Albumen semini conforme.

Embryo exiguus, prope hilum seminis situs, immersus. Coty-

ledones majusculæ, r'otundatæ. Radicula parva, ad hilum

seminis versa.

T ree of a middle size, erect, but flexuose; the bark ash-coloured,'

rimose ; the wood red, fragile.

Branches alternate, flexuose, patent, covered with, a brown

. bark, the younger ones glutinous.

Leaves alternate, petiolate, obovate, rounded, the point very

obtuse and often emarginate, the margin somewhat lobed,

waved, obtusely serrated, smooth, viscid, veined, deep

green, paler .beneath, with prominent nerves which at

their axilla; are hairy.

Peduncles of the male and female flowers terminal, branched,

somewhat downy, brown; pedicels tuberculate.

.Flowers amentaceous.

Male Aments two or three inches long, cylindrical, pendulous.

..

Perianth double. Calyx a reddish-brown pedicellate scale,

beneath having three squamules, three-flowered a t the

base. Corolla four-partite, the segments rounded.

Stamens four, inserted below the middle of the segments of the

corolla. Filaments short. Anthers rotundato-quadrate,

yellow, two-celled. Pollen small, spherical, yellow.

Female Ament ovate, obtuse, erect, two or three lines long,

often bearing a monstrous leafy excrescence; its colour,

is at first sanguineous, then brownish-green, after the fall

of the seeds blackish.

Perianth simple. »Scales ovato-cordate, densely imbricated,

camose, sanguineous, within at the base fiirnished with

two obcordate green squamules, at first small, at length

as large as the scale, two-flowered.

Ovary ovate, compressed. Styles filiform, longer than the

scale.

Pericarp an ovato-roundish, compressed, pale-brown nucule,

terminated by the persistent styles, two-celled, cells one-

seeded. Shell hard.

Seed almost aslarge as the cell, ovato-oblong, somewhat oblique,

pendent, affixed to the apex of the cells.

Integument membranaceous, thin.

Albumen of the same shape as the seed.

E mbryo small, situated near the hilum of the seed, immersed.

Cotyledons rather large, roundish. Radicle small, directed

towards the hilum of the seed.

Fig. I. Scale of the male flower. Fig. 2. Ditto, seen in front. Fig. 3. Flower detached. Fig. 4. Anther. Fig. 5. Pollen.

Fig. 6. Female ament. Fig. 7. Scale of flower. Fig. 8. Scale, the flower removed to show the squamules. Fig. 9- Scale

of the fruit. Fig. 10. Ditto, anterior view of, with two capsules and enlarged squamules, 0Fig. 11. Nucule, vertically cut

open, to show the two cells and the insertion of the seeds. Fig. 12. The same horizontally cut open. Fig. 13. Seed. Fig. 14.

. Ditto, vertically cut open, to show the albumen and the situation of the embryo. Fig. 15. Embryo. All more or less magnified.

The genus Alnus was distinguished from Betula by Tournefort, but united to it by Linna?us and most succeeding authors;

again separated by Gtertner; and botanists are now generally satisfied of the propriety of so doing.. The most essential mark of

distinction is to be found in the winged pericarp of Betula and the naked one of Alnus.

The common Alder is a tree familiar to the most casual observer, growing frequently by the banks of rivers, in meadows occasionally

overflowed, and marshy situations; but no where perhaps in greater beauty or luxuriance than in the moist valleys of the

highlands of Scotland.

Its flowers are amongst the earliest heralds of spring, being frequently expanded in the latter end of February or early in

March, and are then succeeded by the leaves. The male catkins are found in the autumn, continuing unexpanded during the rigour

of the.winter months.

Almost every part o f the tree has its uses in the arts or in domestic economy. In Scotland, according to Lightfoot, the leaves

are employed in tanning leather and as food for sheep, and in some parts of France they are given dry to the cattle during winter.

Kramer says that ulcers may be healed by them, and Lamarck in his Hictionnaire tells us that a decoction prepared from them is

employed in the cure of sore throats. The bark is very astringent, and is used by fishermen to stain their nets. With the addition

of copperas it gives a black dye, of which an ink may be made.. Linnteus assures us that the Laplanders,extract a dye from^the

inner bark by masticating it in their mouths till their saliva is deeply tinged with re d ; with this their shoes, girdles, and all articles

made of skin are stained. The branches serve to make charcoal, and the knots of the trunk are beautifully veined, and are used

by cabinet-makers for ornamental work.

The wood when first cut down is of a fine red colour, but this is not durable: it is much employed by our wheelwrights, turners,

and patten-makers,»and by the French in making their sabots (or wooden shoes). In Norway and Iceland, the vessels for holding

milk are made of it, and Linnaeus observes, that the milk kept in them gives a larger quantity of cream.. But the great value of this

wood consists in the property it possesses of remaining sound under water for a great number of years, on which account piles

driven into wet or boggy ground are made of it, and it is frequently used for such purposes in Venice and in Holland. Water-

pipes are formed of it, and these after lying long buried in a damp situation, are found almost as black as ebony.

The highlanders of Scotland make chairs of the wood, which are said to be very handsome and the colour of mahogany.

Theophrastus makes mention of the bark as affording a dye for skins; and Pliny speaks of the durability of the wood tor piles

and water-pipes, and also that it was planted by the sides of rivers Jo keep the waters within bounds.

flo> , «