fortunate; he was then as a child attached to Penam

monastery, twenty miles west of Gyantse, and his

life was made so miserable there by the brutality of

the lamas that, while still a boy, he ran away and went

to Lhasa. He must have been a boy of character and

audacity, for such insubordination as that is almost

inconceivable in a lamaic acolyte. Arrived in Lhasa, he

attached himself to a doctor, and after some years of

apprenticeship he came to practise in this village of

Jang-kor-yang-tse. Three years ago, tired of the small

scope which this little village afforded him in his profession,

he had intended to return to Lhasa. The

lamas, with whom he was on the friendliest terms

were m despair at the thought of losing his services!

In Tibet there are ways and means unknown to western

nations, and as the succession of incarnations in this

gompa happened then to be in abeyance, a hurried

despatch was sent to Lhasa, with the result that our

friend was, to his own intense amazement, hailed, in

his twenty-fourth year, as the long-lost successor of

the Bodisats of Jang-kor-yang-tse. Sitting cross-legged

on his little dais in front of the square latticed windows

which kept the bright heads of hollyhocks from falling

into the room, he told us his story, and I confess I

wondered at the time whether he were not, even then

yearning for his old life of less sanctity and greater

freedom. He explained that he had intended to pay

a visit of courtesy to Colonel Younghusband, but had

been restrained through fear of the Lhasan Government.

Turning to O’Connor, he asked, with unaffected simplicity.

Tell me, under which government am I ? Are the

English or the Tibetans lords of this valley ? ”

During the interview a dozen of the senior lamas

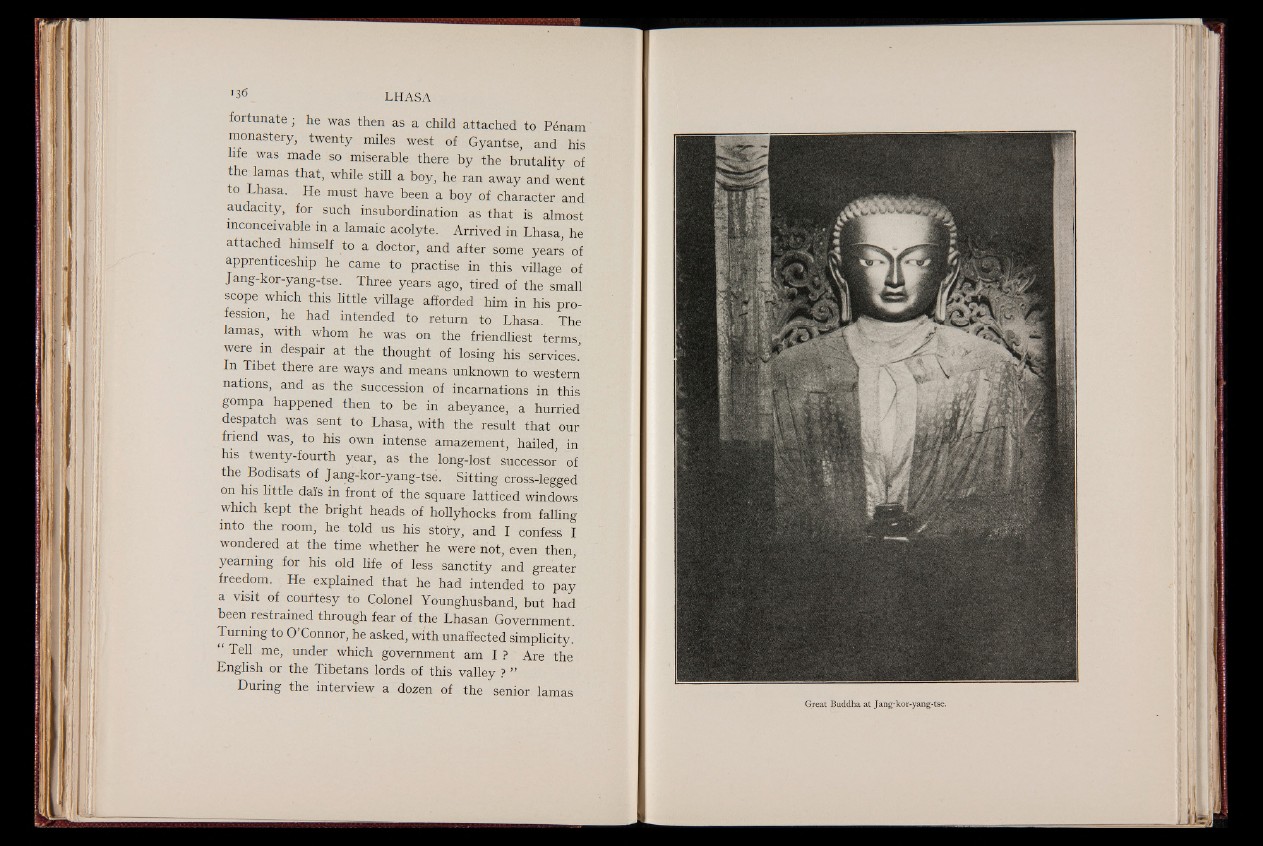

Great Buddha at Jang-kor-yang-tse.