then fluffed out on either side and fall down over the

shoulders. It is one of the most becoming ways of doing

the hair that I have ever seen, and for a certain type

the entire dress of a woman of Lhasa would be a not

unbecoming costume for a fancy dress ball at home.

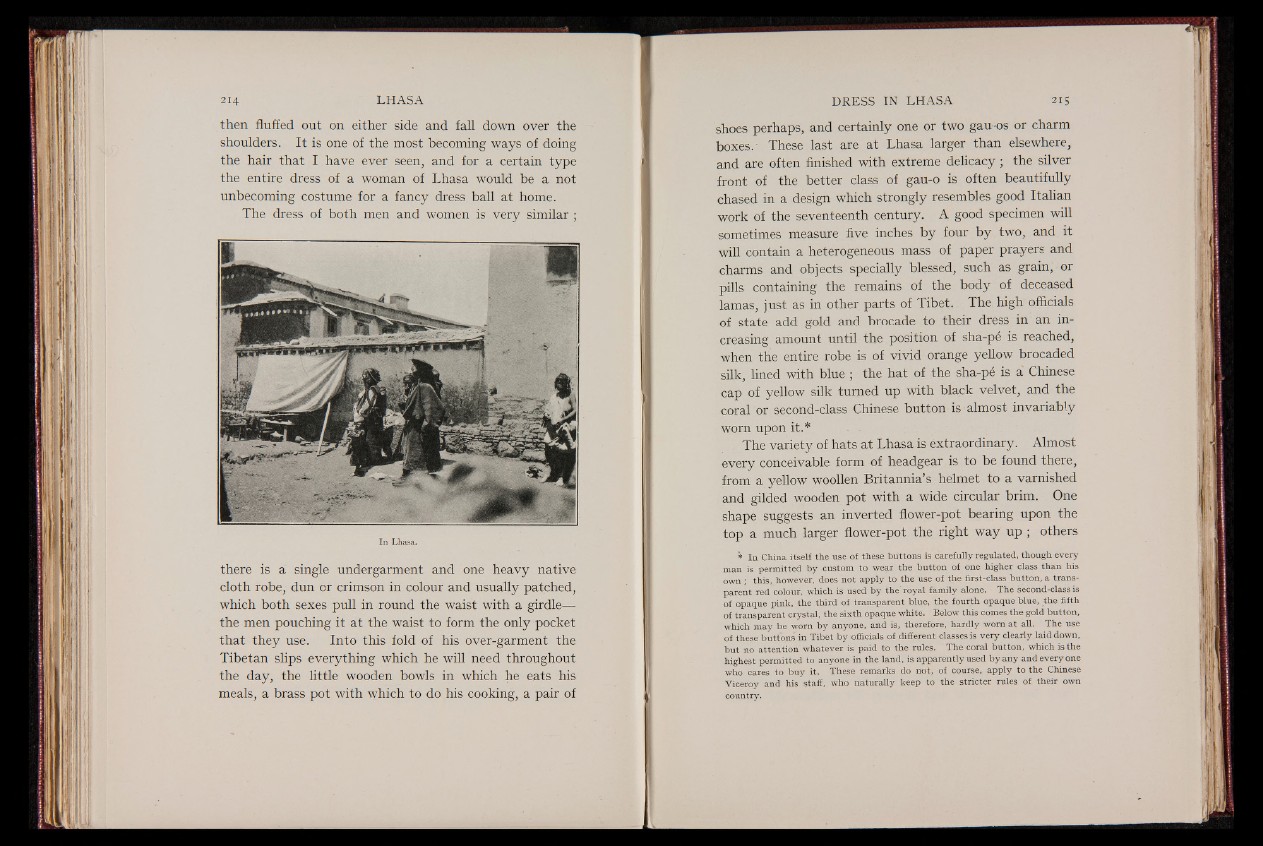

The dress of both men and women is very similar ;

In Lhasa.

there is a single undergarment and one heavy native

cloth robe, dun or crimson in colour and usually patched,

which both sexes pull in round the waist with a girdle—

the men pouching it at the waist to form the only pocket

that they use. Into this fold of his over-garment the

Tibetan slips everything which he will need throughout

the day, the little wooden bowls in which he eats his

meals, a brass pot with which to do his cooking, a pair of

shoes perhaps, and certainly one or two gau os or charm

boxes. These last are at Lhasa larger than elsewhere,

and are often finished with extreme delicacy ; the silver

front of the better class of gau-o is often beautifully

chased in a design which strongly resembles good Italian

work of the seventeenth century. A good specimen will

sometimes measure five inches by four by two, and it

will contain a heterogeneous mass of paper prayers and

charms and objects specially blessed, such as grain, or

pills containing the remains of the body of deceased

lamas, just as in other parts of Tibet. The high officials

of state add gold and brocade to their dress in an increasing

amount until the position of sha-pe is reached,

when tlie entire robe is of vivid orange yellow brocaded

silk, lined with blue ; the hat of the sha-pe is a! Chinese

cap of yellow silk turned up with black velvet, and the

coral or second-class Chinese button is almost invariably

worn upon it.*

The variety of hats at Lhasa is extraordinary. Almost

every conceivable form of headgear is to be found there,

from a yellow woollen Britannia’s helmet to a varnished

and gilded wooden pot with a wide circular brim. One

shape suggests an inverted flower-pot bearing upon the

top a much larger flower-pot the right way up ; others

* In China itself the use of these buttons is carefully regulated, though every

man is permitted b y custom, to wear the button of one higher class than his

own ; this, however, does not apply to the use of the first-class button, a transparent

red colour, which is used b y the royal family alone. The second-class is

of opaque pink, the third of transparent blue, the fourth opaque blue, the fifth

of transparent crystal, the sixth opaque white. Below this comes the gold button,

which may be worn b y anyone, and is, therefore, hardly worn a t all. The use

of these buttonsf in Tibet b y officials of different classes is very clearly laid down,

but no attention whatever is paid to the rules. The coral button, which is the

highest permitted to anyone in the land, is apparently used b y any and every one

who cares to buy it. These remarks do not, of course, apply to the Chinese

Viceroy and his staff, who naturally keep to the stricter rules of their own

country.