tions, fields and houses all the way up to where the

wind-blown buttresses of sand blanket the hollow scarp

of the southern hills. Far away in the distance beyond,

the town the plain still stretches, always the same

marshy expanse jagged and indented by the spurs of

the encircling hills; six miles away it closes in to the

east at the point to which the curving thread of the high

road to China makes its uncertain way, banked high

across the morass.

Just where the dun town encroaches upon the greenery

you may see clearly the famous Yutok Sampa or Turquoise

roofed bridge. To the right is the Amban’s

house, almost completely hidden in its trees, and on

the other side of the Jo-kang’s gilded canopies, far away

to the left, rise the steep, unbeautiful walls of the Meru

gompa, the last house in Lhasa to the north-east; to

the west of it, amid the greenery of its plantations,

flash the golden ridge-poles of Ramo-che, after the Jo-

kang itself the most sacred of all temples in Tibet. But,

believe me, when you have marked these historic points

the eye will helplessly revert again to the Potala ; it is

a new glory added to the known architecture of the

world.

Nothing in Lhasa, excepting always the interior of

the Jo-kang, comes up to this magnificent prelude. If

a traveller knows that the cathedral doors are hopelessly

shut to him, his wisest course would be to sit a day or

two upon this spur of Chagpo-ri and then depart,

making no further trial of the town ; for he will never

catch again that spell of almost awed thanksgiving that

there should be so beautiful a sight hidden among these

icy and inaccessible mountain crests, and that it should

have been given to him to be one of the few to see it.

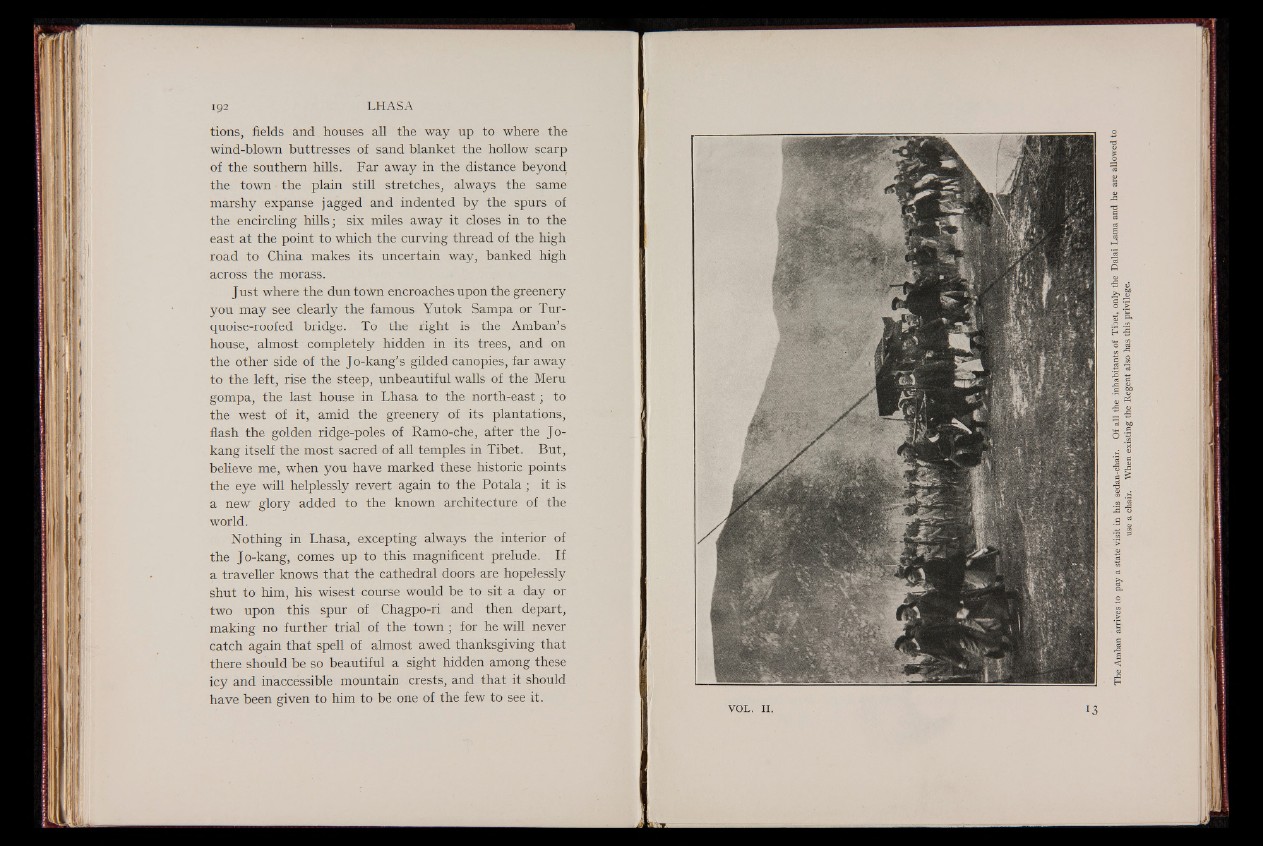

chair. When existing the Regent also has this privilege.