monstrous representation of a flayed human skin, were

opened for us and we went inside into the temple itself.

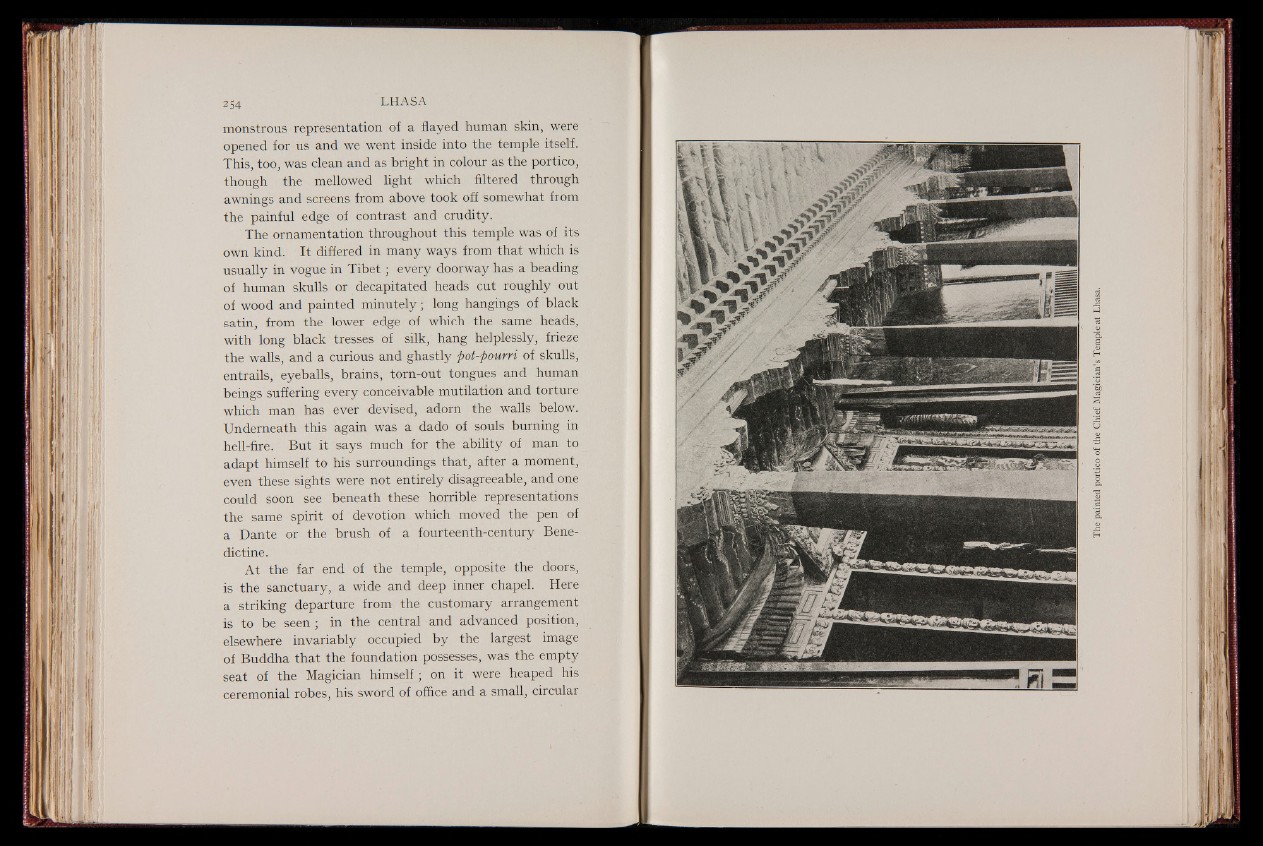

This, too, was clean and as bright in colour as the portico,

though the mellowed light which filtered through

awnings and screens from above took off somewhat from

the painful edge of contrast and crudity.

The ornamentation throughout this temple was of its

own kind. It differed in many ways from that which is

usually in vogue in T ib e t ; every doorway has a beading

of human skulls or decapitated heads cut roughly out

of wood and painted minutely ; long hangings of black

satin, from the lower edge of which the same heads,

with long black tresses of silk, hang helplessly, frieze

the walls, and a curious and ghastly pot-pourri of skulls,

entrails, eyeballs, brains, torn-out tongues and human

beings suffering every conceivable mutilation and torture

which man has ever devised, adorn the walls below.

Underneath this again was a dado of souls burning in

hell-fire. But it says much for the ability of man to

adapt himself to his surroundings that, after a moment,

even these sights were not entirely disagreeable, and one

could soon see beneath these horrible representations

the same spirit of devotion which moved the pen of

a Dante or the brush of a fourteenth-century Benedictine.

At the far end of the temple, opposite the doors,

is the sanctuary, a wide and deep inner chapel. Here

a striking departure from the customary arrangement

is to be seen ; in the central and advanced position,

elsewhere invariably occupied by the largest image

of Buddha that the foundation possesses, was the empty

seat of the Magician himself ; on it were heaped his

ceremonial robes, his sword of office and a small, circular