Twenty years have passed since Ugyen Gyatso, one

of the best of our native explorers, corrected, inadequately

enough, but to the best of his ability, the

traditional delusion as to the shape of the Sacred Lake

of Tibet. Travelling in disguise and almost by

stealth, his opportunities were limited, but his map of

the Yam-dok tso was the first improvement upon

D ’Anville’s 1735 design, and it is probable that to this

day the common conception of this strange sheet of

water is that originated by the Jesuit-taught Lamas of

1717, and repeated without any great variation by every

atlas down to 1884. But the Yam-dok tso is by no means

a symmetrical ring of water surrounding a similar ring

of land. Lieutenant-Colonel Waddell uses the happy

expression “ scorpionoid ” to describe its real shape.

It is not, perhaps, surprising that our ignorance of

what is undoubtedly the most interesting inland sea

of Asia should have been so profound. Its claim to

sacred isolation has been respected far more than that

of Lhasa itself. For every one who has ever set eyes on

the Yam-dok tso, four or five foreigners have seen Lhasa.

Indeed, we do not certainly know that before this ex-

pedition any Europeans except Manning and della

Penna s company had ever passed along the margin

of the long, narrow waters which mean so much to the

superstitious Tibetan peasant, and from Manning, the

incurious, we learn little indeed, except that the water

is bad— a wholly misleading statement, for though the

taste is somewhat alkaline, neither salt nor entirely

fresh, it is wholesome and clean.*

The Tibetans themselves, besides the name Yam-

* Lakes with no outlet inevitably become salt in the lapse of centuries. The Yam-

dok tso must have had some point of escape— probably the Rongchu-at a comparatively

recent period.

dok tso, or “ high grazing lake,” use another, “ Yu-tso,”

or the “ Turquoise Lake,” and it is impossible to

describe more exactly the exquisite shade of blue-green

which colours the waters under even the most

brilliant azure skies. Near inshore the innumerable

ripples are, indeed, blown in over the white-sanded

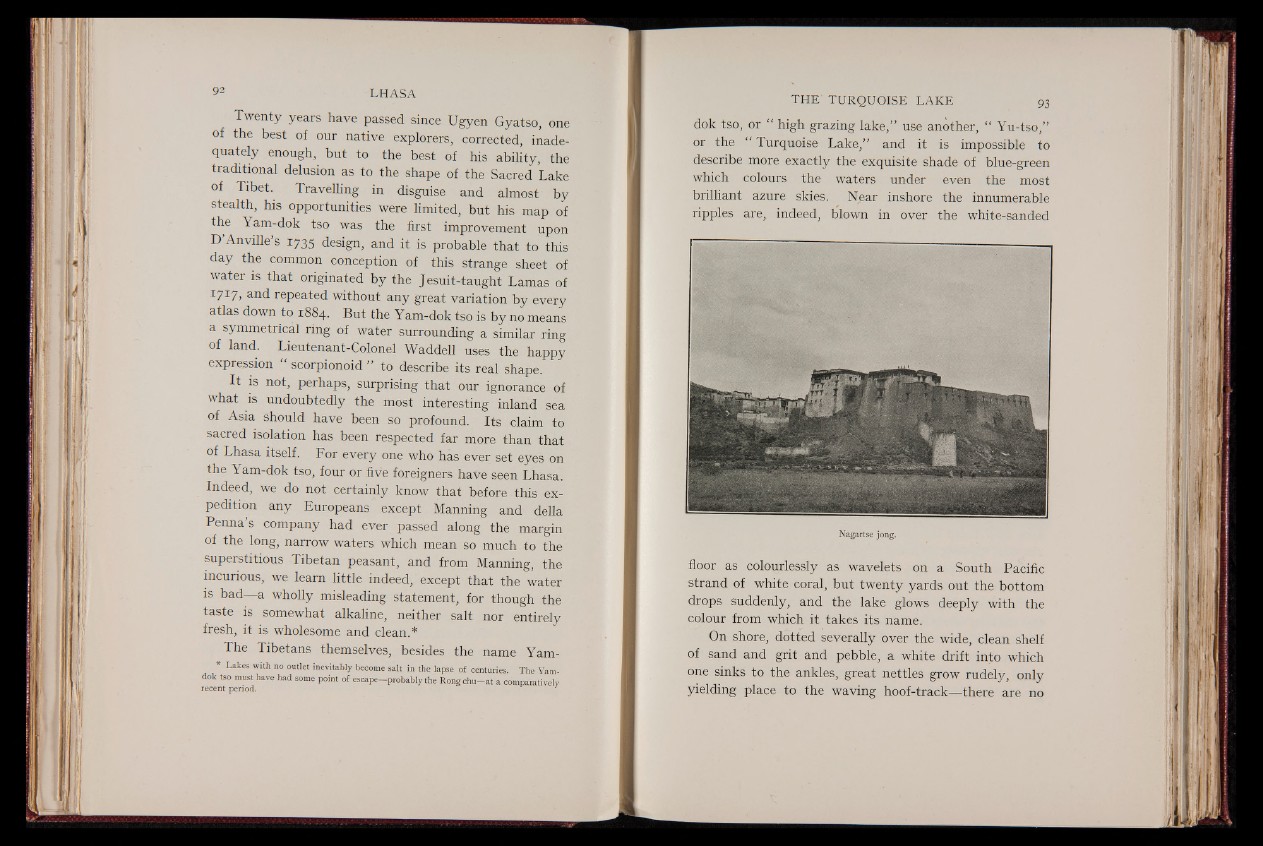

Nagartse jong.

floor as colourlessly as wavelets on a South Pacific

strand of white coral, but twenty yards out the bottom

drops suddenly, and the lake glows deeply with the

colour from which it takes its name.

On shore, dotted severally over the wide, clean shelf

of sand and grit and pebble, a white drift into which

one sinks to the ankles, great nettles grow rudely, only

yielding place to the waving hoof-track— there are no