horns of cattle.* These men exact high fees for disposing

ceremonially of dead bodies. The limbs and

trunk of the deceased person are hacked apart and

exposed on low flat stones until they are consumed by the

clogs, pigs and vultures with which Lhasa swarms. The

flesh of the pigs is highly esteemed in Lhasa, and indeed

to the taste it is as good as most pork ; but after you

have seen the Ragyaba quarter and heard the story of

the manner in which the Tibetans dispose of their dead,

you will be little inclined to eat it again.

Chandra Das reports that these Ragyabas are recognised

by the authorities as a tribe of refuge for all the

rascals in the country, whose place of origin cannot be

ascertained ; he also mentions a curious legend that if a

day passes without a burial, if the word may be used,

ill-fortune is certain to overtake Lhasa, f Recruited

from such sources, accustomed to live among surroundings

more disgusting by far than those of the Australian

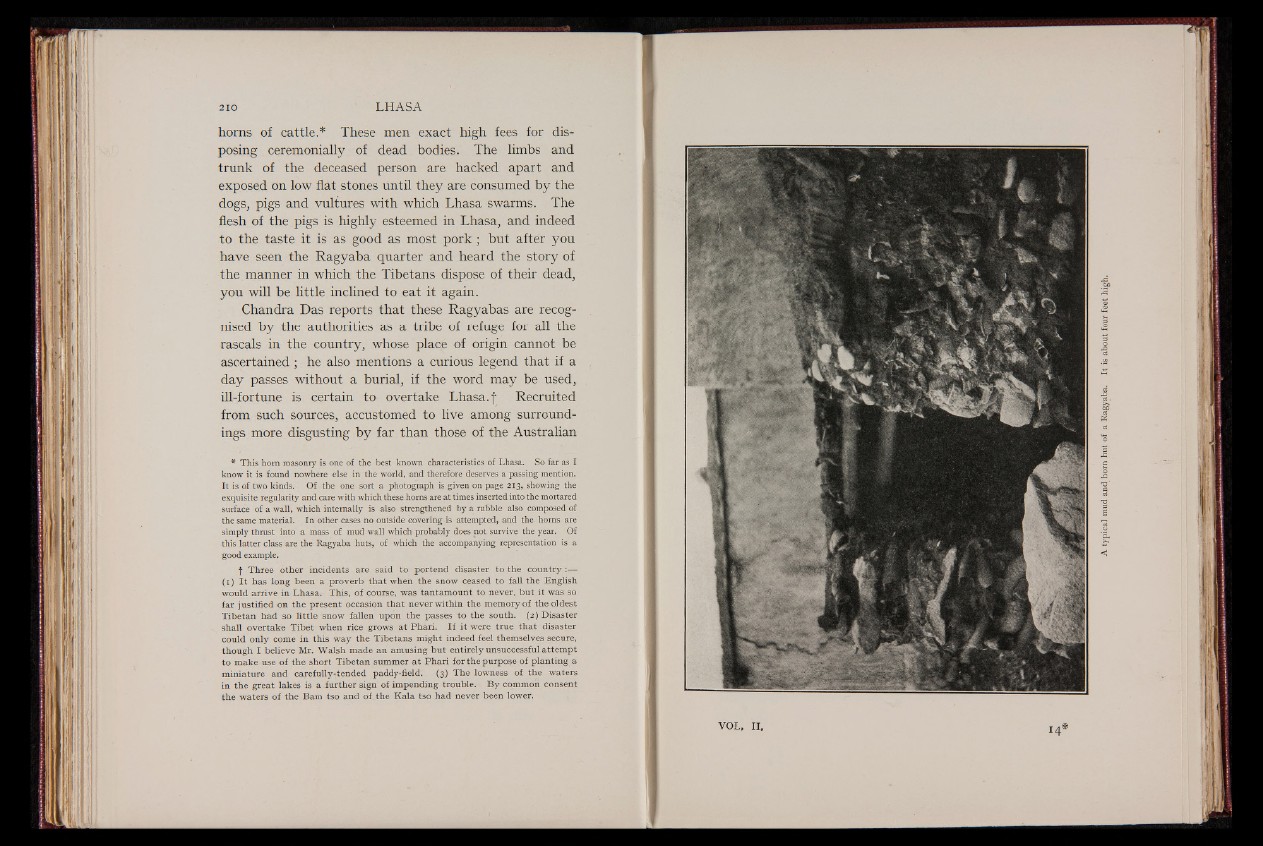

* This horn masonry is one of the best known characteristics of Lhasa. So far as I

know it is found nowhere else in the world, and therefore deserves a passing mention.

It is of two kinds. Of the one sort a photograph is given on page 213, showing the

exquisite regularity and care with which these horns are at times inserted into the mortared

surface of a wall, which internally is also strengthened by a rubble also composed of

the same material. In other cases no outside covering is attempted, and the horns are

simply thrust into a mass of mud wall which probably does not survive the year. Of

this latter class are the Ragyaba huts, of which the accompanying representation is a

good example.

f Three other incidents are said to portend disaster to the country

(1) I t has long been a proverb that when the snow ceased to fall the English

would arrive in Lhasa. This, of course, was tantamount to never, but it was so

far justified on the present occasion that never within the memory of the oldest

Tibetan had so little snow fallen upon the passes to the south. (2) Disaster

shall overtake Tibet when rice grows at Phari. I f it were true that disaster

could only come in this way the Tibetans might indeed feel themselves secure,

though I believe Mr. Walsh made an amusing but entirely unsuccessful attempt

to make use of the short Tibetan summer a t Phari for the purpose of planting a

miniature and carefully-;tended paddy-field. (3) The lowness of the waters

in the great lakes is a further sign of impending trouble. B y common consent

the waters of the Bam tso and of the Ka la tso had never been lower.