now the river made a weir of it, pouring over it in a dirty,

clouded stream, and you might hear the roar of it at

the ferry half a mile up the river. At the shore end

the abutments and anchorages rise at the foot of a

tidy-looking monastery, set among the steep rocks of

the basalt hillj here cut and painted with raw images

in white and blue, -daubed with raddle, crested with

chortens and flagged sheaves of carving innumerable

with the inevitable om mani padme hum. The bridge

itself is gone, only the chains remain; slings and footway

alike have disappeared, but there is scarcely a sign

of rust or clogging to be seen on the iron.

The Tibetans themselves have long been accustomed

to rely upon the ferry. In their retreat from

their southern and western positions, they had neglected

to destroy the two ferry-boats, to our great advantage.

It is difficult to imagine what we should have done

without them. Each of these great arks is an oblong

lighter, forty feet by twelve, with a four-foot freeboard,

and a quaintly carved' horse’s head at the bows.

The transport of the troops across the river was enormously

hastened by the device used by Captain Sheppard.

He turned these two boats into swinging, bridges,

by the aid o f . stout ropes running on a carrier backwards

and forwards along a steel wire hawser,-which he

here threw across the 120 yards of whirling and swollen

brown water. In this way the interminable waste of

time, caused by the necessary drift down stream of the

big boats in their passages across, , was prevented, and

what had previously taken an hour— with occasional

intervals of three hours, during which the boat had

lumbered two miles down stream, and had to be pain-

fully retrieved and towed back— now took but twenty

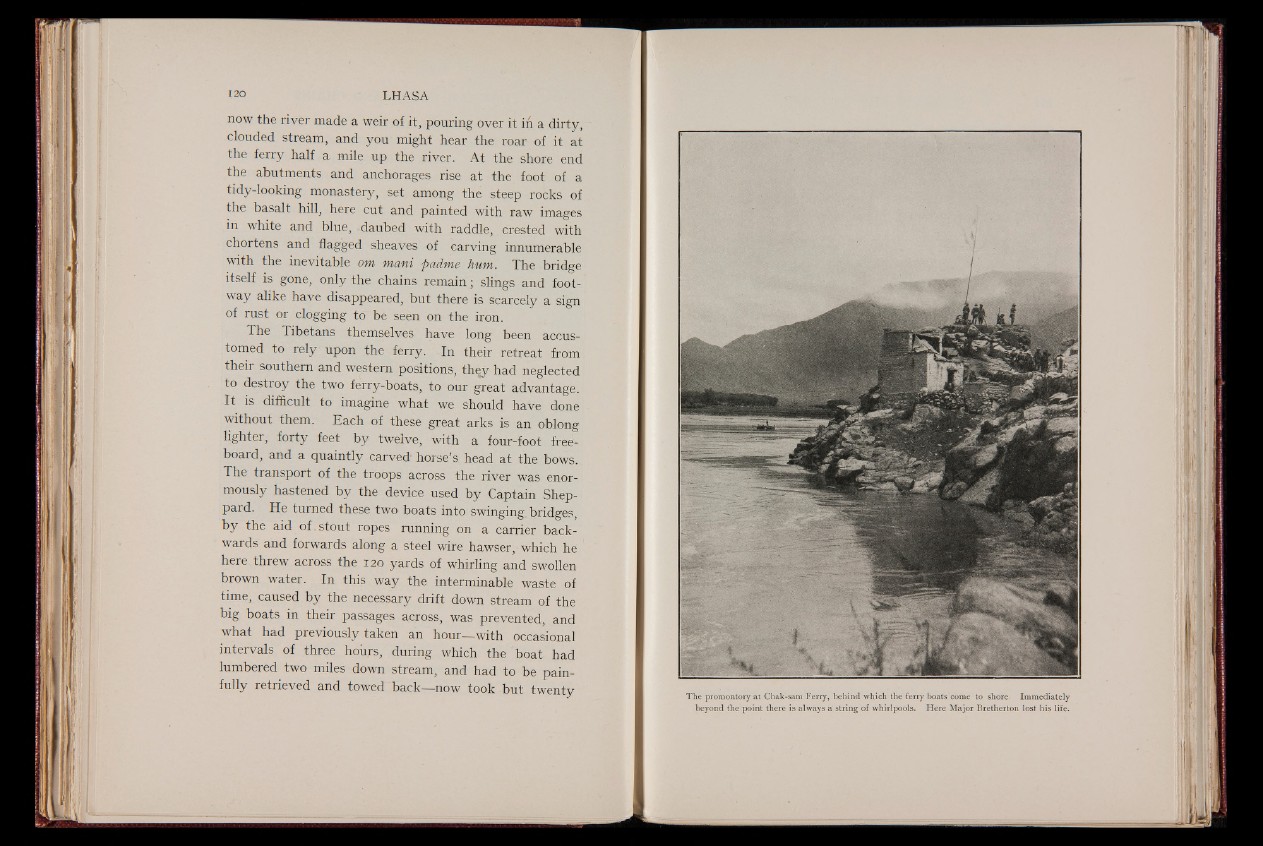

The promontory at Chak-sam Ferry, behind which the ferry boats come to shore. Immediately

beyond the point there is always a' string of whirlpools. Here Major Bretherton lost his life.