mud, through and over which one has gingerly to pick

one’s way, stepping from stone to stone, enters the

house as freely as ourselves, and in the sudden dark

one can only just distinguish the corner down which a.

precipitous ladder slants. It is impossible here to choose

one’s steps, so one plunges through the mud and stones

to reach the base of the ladder, which, it must be

remembered, is the only way in which a visitor or

resident, high or low, can reach the house itself. Up

the slippery iron-sheathed treads one goes, clinging

desperately to the polished willow handrail, and at the

top one is confronted across the passage by the durbar

room of the house.

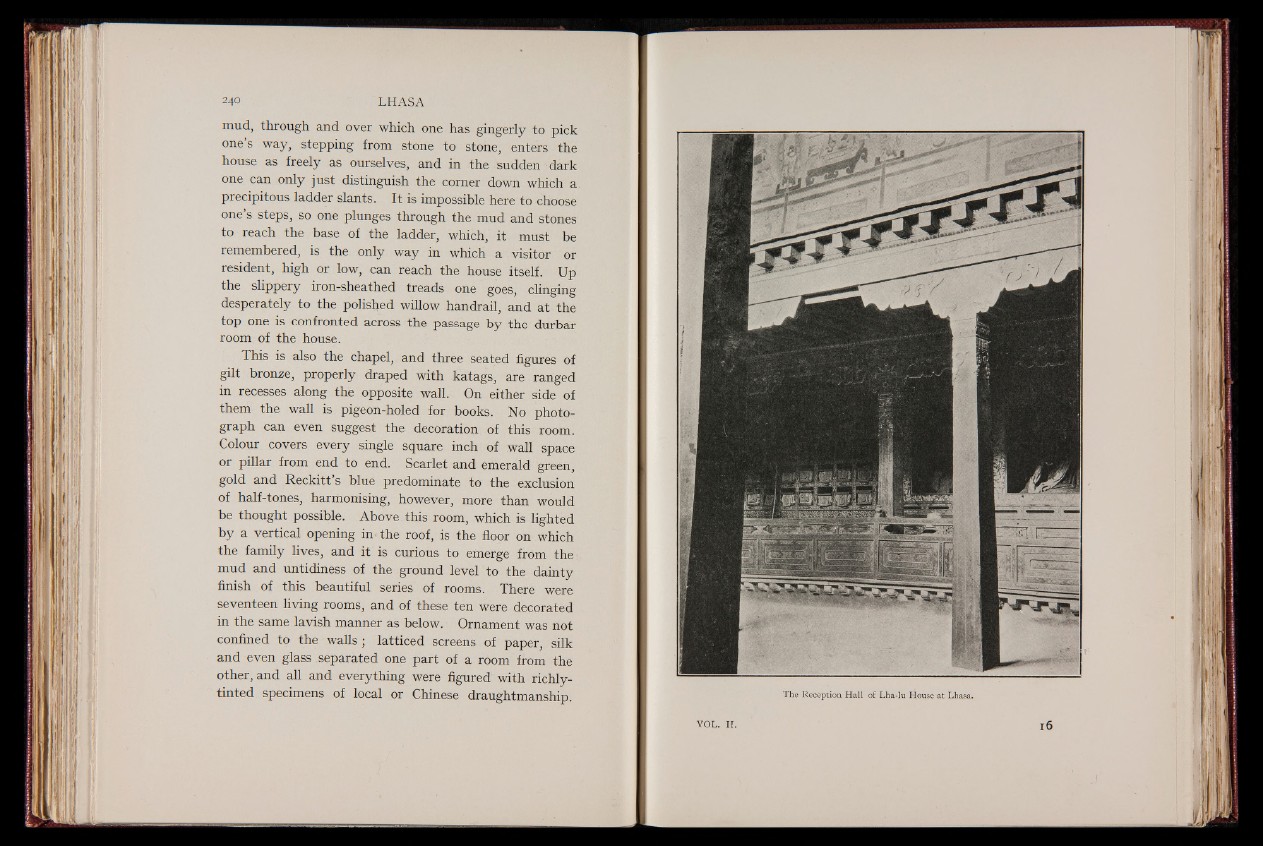

This is also the chapel, and three seated figures of

gilt bronze, properly draped with katags, are ranged

in recesses along the opposite wall. On either side of

them the wall is pigeon-holed for books. No photograph

can even suggest the decoration of this room.

Colour covers every single square inch of wall space

or pillar from end to end. Scarlet and emerald green,

gold and Reckitt s blue predominate to the exclusion

of half-tones, harmonising, however, more than would

be thought possible. Above this room, which is lighted

by a vertical opening in- the roof, is the floor on which

the family lives, and it is curious to emerge from the (

mud and untidiness of the ground level to the dainty

finish of this beautiful series of rooms. There were

seventeen living rooms, and of these ten were decorated

in the same lavish manner as below. Ornament was not

confined to the walls ; latticed screens of paper, silk

and even glass separated one part of a room from the

other, and all and everything were figured with richly-

tinted specimens of local or Chinese draughtmanship. The Reception Hall of Lha-lu House at Lhasa.