orders of the Government, to compel his acquiescence in

a non-military solution of the difficulties. Here the

roles were reversed with a vengeance.

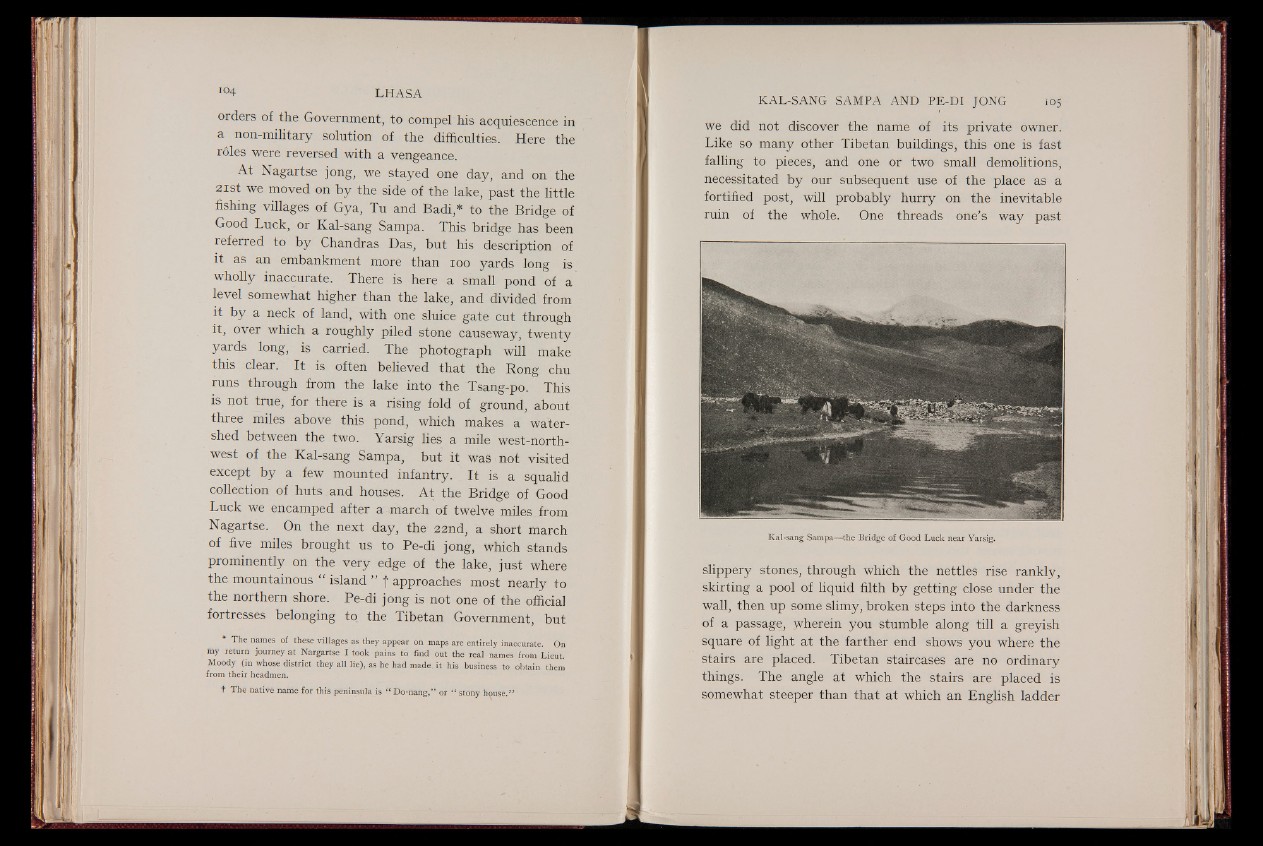

At Nagartse jong, we stayed one day, and on the

21st we moved on by the side of the lake, past the little

fishing villages of Gya, Tu and Badi,* to the Bridge of

Good Luck, or Kal-sang Sampa. This bridge has been

referred to by Chandras Das, but his description of

it as an embankment more than 100 yards long is

wholly inaccurate. There is here a small pond of a

level somewhat higher than the lake, and divided from

it by a neck of land, with one sluice gate cut through

it, over which a roughly piled stone causeway, twenty

yards long, is carried. The photograph will make

this clear. It is often believed that the Rong chu

runs through from the lake into the Tsang-po. This

is not true, for there is a rising fold of ground, about

three miles above this pond, which makes a watershed

between the two. Yarsig lies a mile west-north-

west of the Kal-sang Sampa, but it was not visited

except by a few mounted infantry. It is a squalid

collection of huts and houses. A t the Bridge of Good

Luck we encamped after a march of twelve miles from

Nagartse. On the next day, the 22nd, a short march

of five miles brought us to Pe-di jong, which stands

prominently on the very edge of the lake, just where

the mountainous “ island ” f approaches most nearly to

the northern shore. Pe-di jong is not one of the official

fortresses belonging to the Tibetan Government, but

* The names of these villages as they appear on maps are entirely inaccurate. On

ihy return journey at Nargartse I took pains to find out the real names from Lieut.

Moody (in whose district they all lie), as he had made, it his business to obtain them

from their headmen.

t The native name for this peninsula is “ Do-nang,” or “ stony house.”

K A L -SAN G SAM P A AN D PE-DI JONG 105

we did not discover the name of its private owner.

Like so many other Tibetan buildings, this one is fast

falling to pieces, and one or two small demolitions,

necessitated by our subsequent use of the place as a

fortified post, will probably hurry on the inevitable

ruin of the whole. One threads one’s way past

Kal-sang Sampa— the Bridge of Good Luck near Yarsig.

slippery stones, through which the nettles rise rankly,

skirting a pool of liquid filth by getting close under the

wall, then up some slimy, broken steps into the darkness

of a passage, wherein you stumble along till a greyish

square of light at the farther end shows you where the

stairs are placed. Tibetan staircases are no ordinary

things. The angle at which the stairs are placed is

somewhat steeper than that at which an English ladder