every ledge. On the top of this ascent one looks away

over the wide waste of the Kyi chu river, and there are

few sights in the world more beautiful than that which

here meets the eye. Far and wide the sunlit river

stretches its shallows ; one could almost believe that

Lhasa was an island in a lake, and the picturesque foliage

of the trees and flowers that rise at the foot of the long

slaty cliffs, just where the southern sunshine washes

them all day and the rock gives out its warmth to them

all night, are more luxuriant than anywhere else beside

the sacred way. The Ling-kor descends here somewhat

abruptly, finding a foothold at the base of the rocks by

which you may climb from here to Chagpo-ri— it is as

it were the sprawled near hind-leg of the couching lion

of stone.

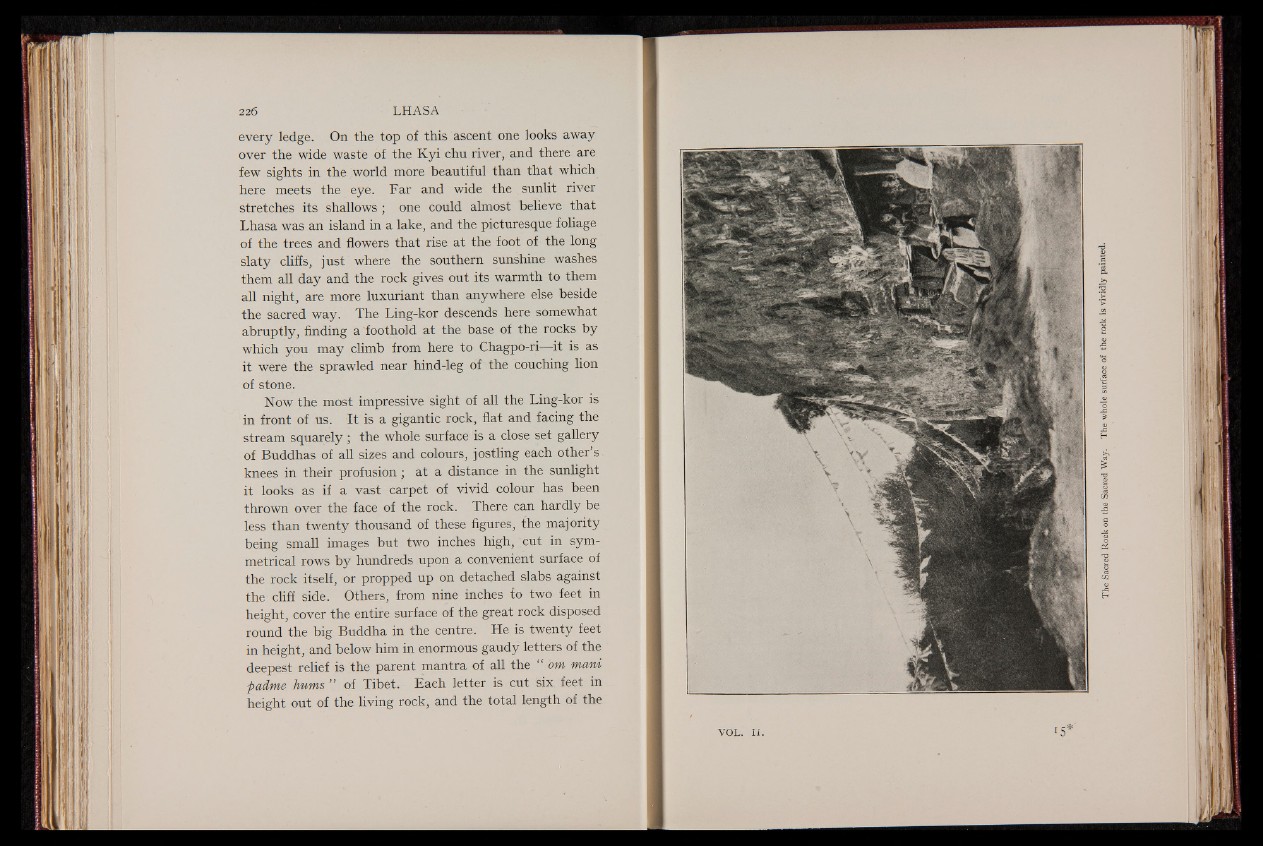

Now the most impressive sight of all the Ling-kor is

in front of us. It is a gigantic rock, flat and facing the

stream squarely ; the whole surface is a close set gallery

of Buddhas of all sizes and colours, jostling each other’s

knees in their profusion ; at a distance in the sunlight

it looks as if a vast carpet of vivid colour has been

thrown over the face of the rock. There can hardly be

less than twenty thousand of these figures, the majority

being small images but two inches high, cut in symmetrical

rows by hundreds upon a convenient surface of

the rock itself, or propped up on detached slabs against

the cliff side. Others, from nine inches fo two feet in

height, cover the entire surface of the great rock disposed

round the big Buddha in the centre. He is twenty feet

in height, and below him in enormous gaudy letters of the

deepest relief is the parent mantra of all the “ om mani

padme hums ” of Tibet. Each letter is cut six feet in

height out of the living rock, and the total length of the