turned down, and one found that half a hundred stars

were already blinking whitely in the grey-blue depths.

On the next day we went on to Chak-sam ferry, a

distance of about six miles. The valley of the Tsang-po

is different indeed from what one had been given to

expect. Instead of a full and racing sweep of water,

cutting its way, like the southern Himalayan streams,

through a densely forested gorge, the yellow volume,

almost without a ripple, swerves and divides itself

across and between a mile-wide stretch of sand, bordered

on either side by a broad strip of well-cultivated

fields of barley, wheat and peas. Here and there are

openings between the hills dotted with the white and

blue of the surrounding houses, and encroached upon

by the wastes of billowy sand, which the tide at first,

and the wind afterwards, have banked and shelved

against the base of the hills.* Beside the cool’ lush

greenery of the road, the whitening barley fields were

edged with rank growths of thistles and burdock, and

“ black-veined whites ” and “ orange-tips ” fluttered

over the opened dog-roses. Where the vegetation

ceased, the arid waste of triturated granite running up

to the mountain buttresses is dotted with a kind of

mimosa which seems rarely to obtain a height of more

than two or three feet, but is useful in binding together

the shifting sands of the river bank.

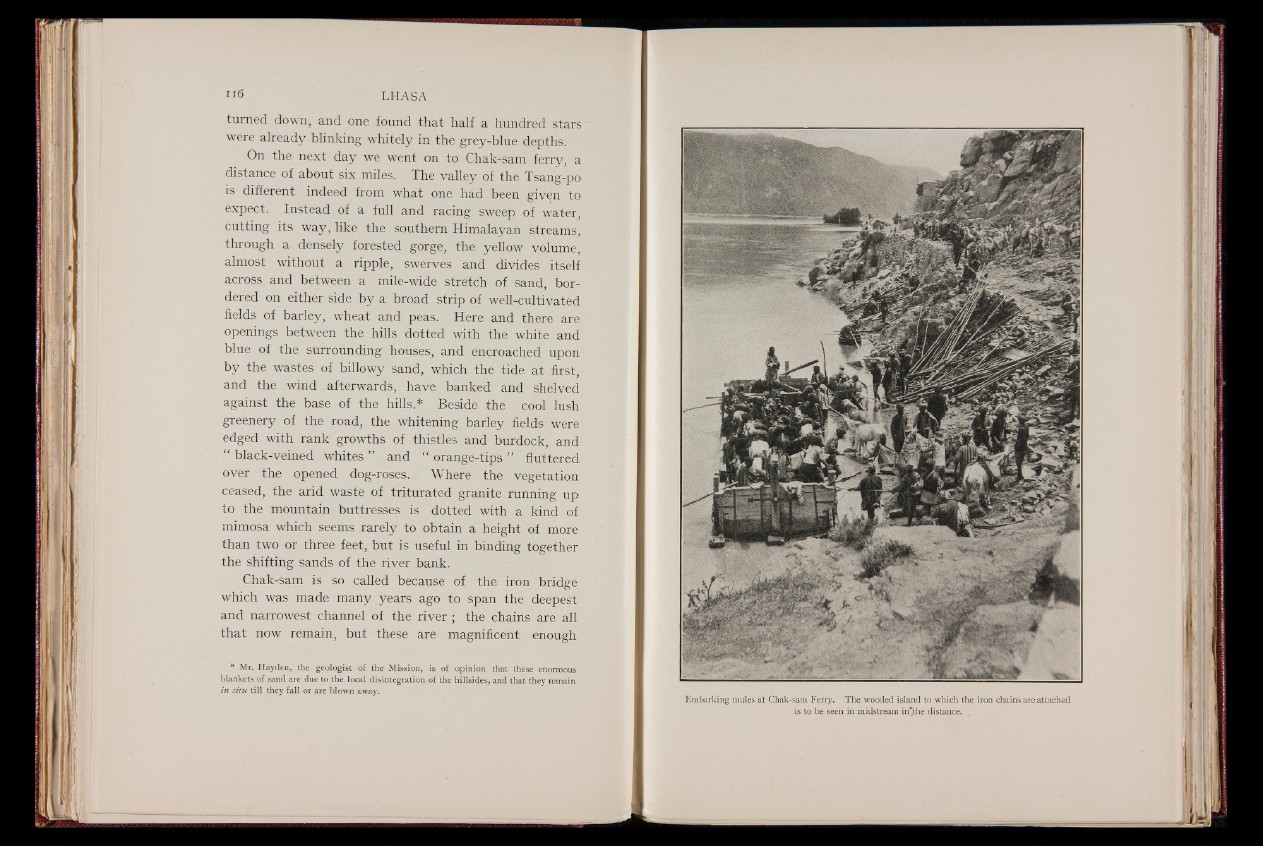

Chak-sam is so called because of the iron bridge

which was made many years ago to span the deepest

and narrowest channel of the river ; the chains are all

that now remain, but these are magnificent enough

* Mr. Hayden, the geologist of the Mission, is of opinion that these enormous

blankets of sand are due to the local disintegration of the hillsides, and that they remain

in s itu till they fall or are blown away.

Embarking mules at Chak-sam Ferry. The wooded island to which the iron chains are attached

is to be seen in midstream in'the distance. ,