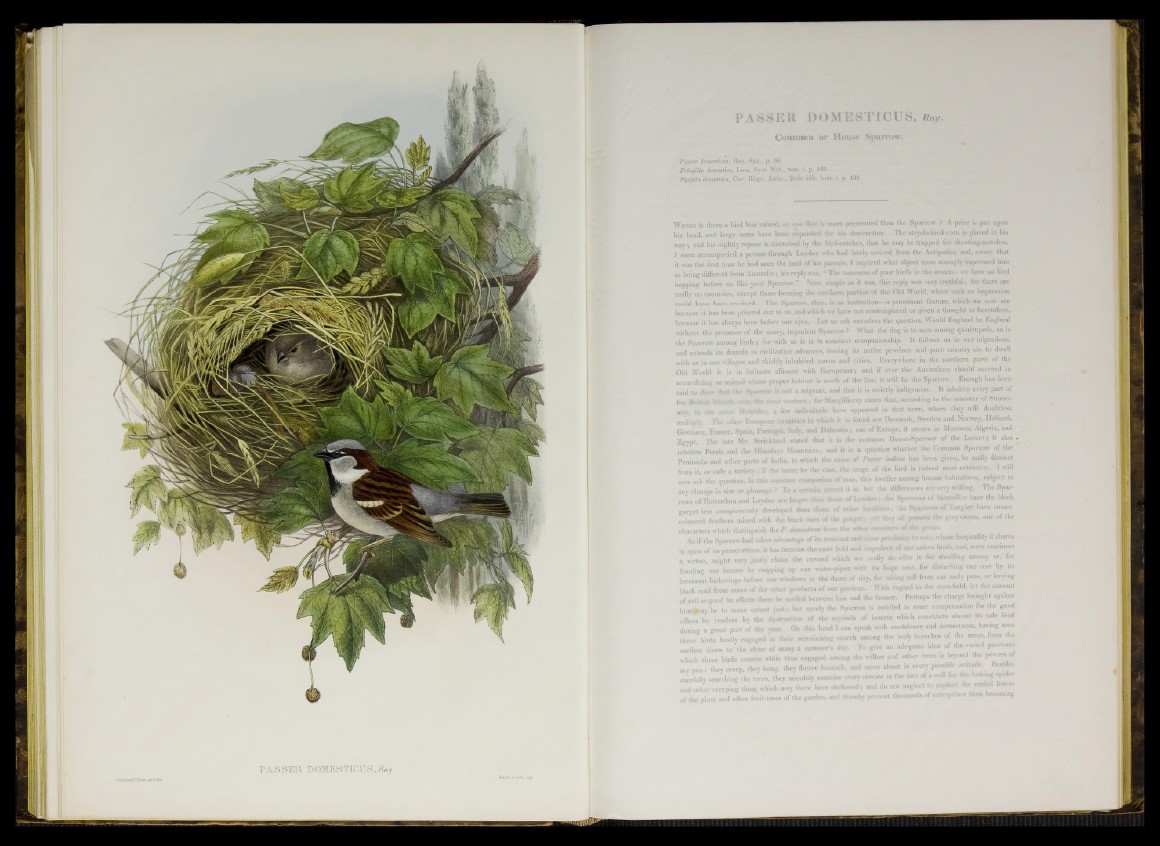

PASSER BOMESTICUS»/%

Common or House Sparrow.

Passer domesticus, Ray, Syn., p. 36.

Fringilta domestica, Linn. Syst. Nat., tom. i. p. 323.

Pyrgita domestica, Cuv. Rfegn. Anun., 2nd« edit. tom. i. p. 439.

W h e re is there a bird less valued, ur one that is more persecuted than the Sparrow ? A price is put upon

his head, and large sums have been expended tor his destruction. The strychnincd corn is placed in his

wayt and his nightly repose is disturbed by the bird-catcher, that he may be trapped for shooting-matches.

I once accompanied a person through London who had lately arrived from the Antipodes, and, aware that

it was the first time he had seen the land of his parents, I inquired what object most strongly impressed him

as being different from A ustralia; his reply was, “ The tameness o f your birds in the s tre e ts : we have no bird

hopping before us like your Sparrow.” Now, simple as it was, this reply was very tru th fu l: for there are

really no countries, except those forming the northern portion of the Old World, wltere such an impression

could have been received. The Sparrow, then, is an institution—a prominent feature, which we now see

because it has been pointed out to us, and which we have not contemplated or given a thought to heretofore,

because it has always been before our eyes. Let us ask ourselves the question, Would England be England

without the presence o f the saucy, impudent Sparrow ? What the dog is to man among quadrupeds, so is

the Sparrow among Birds; for with us it is in constant companionship. I t follows us in our migrations,

and extends its domain as civilisation advances, leaving its native province and pure country air, to dwell

with us in our villages and thickly inhabited towns and cities. Everywhere in the northern parts o f the

Old World it is in intimate alliance with Europeans; and if ever the Australians should succeed in

naturalising an animal whose proper habitat is north of the line, it will be the Sparrow. Enough has been

said to show that the Sparrow is not a migrant, and th at it is strictly indigenous. It inhabits every .part of

the British Wamb. the most western; for Macgillivray states that, according to the minister of Storno-

wav, in tin n o w Hebrides, a few individual, have appeared in that town, where they will doubtless

multiply. The other European countries in which it is found are Deomark, Sweden and Norway, Holland,

Germany, France, Spain, Portugal, Italy, and Dalmatia; out of Europe, it occurs in Morocco, Algeria, and

Egypt. The late Mr. Strickland stated that it is the common House-Sparrow of the Levant; it also .

inhabits Persia and the Himalaya Mountains; and it is a question whether the Common Sparrow of the

Peninsula and other parte o f India, to which the name of Pauer tidicus has been given, be really distinct

from it, o r only a variety ; if the latter be the case, the range o f the bird is indeed most extensive. 1 will

now ask the question. Is this constant companion o f man, this dweller among human habitations, subject to

any change in size o r plumage ? To a certain extent it is, but the differences are very trilling. The Sparrows

o f Rotterdam and Leyden are larger than those o f London; the Sparrows of Marseilles have the black

gorget less conspicuously developed than those o f other localities: the Sparrows o f Tangier have russet

coloured feathers mixed with the black ones o f the gorget , yet they all possess the grey crown, one of the

characters which distinguish the P. domesticus from the other members of the genus.

As if the Sparrow had taken advantage o f its constant and close proximity to man, whose hospitality it shares

in spite o f its persecutions, it has become the most bold and impudent of our native birds, and, were sauciness

a virtue, might very justly claim the reward which we really do offer it for dwelling among us, for

flooding our houses by stopping up our water-pipes with its huge nest, for disturbing our rest by its

incessant bickerings before our windows a t the dawn of day, for taking toll from our early peas, or levying

black mail from some o f the other products of o ur gardens. With regard to the corn-field, let the amount

o f evil or good he effects there be settled between him and the former. Perhaps the charge brought against

him may be to some extent ju s t ; but surely the Sparrow is entitled to some compensation for the good

offices he renders by the destruction o f the myriads o f insects which constitute almost its sole food

during a great p art o f the year. On this head I can speak with confidence and earnestness, having seen

these birds busily engaged in their scrutinizing search among the leafy branches o f the trees, from the

earliest dawn to the close o f many a summer’s day. To give an adequate idea o f the varied positions

which these birds assume while thus engaged among the willow and other trees is beyond the pmrereof

my p en : they creep, they hang, they flutter beneath, and move about in every possible attitude Beside,

carefully searching the trees, they minutely examine every crevice in the foce o f a wall o r t u r mg spi er

and other creeping thing which may there have sheltered; and do not neglect to explore the curled leaves

, , u, _ r .. . „ „ „ i , ,i »i.-rsnh« nrpvpnt thousands of caterpillars of the plum and other fruit-trees o f the garden, ana thereby pre from becoming