J.&mdtb kSCRuhur, dtb d/ Wi

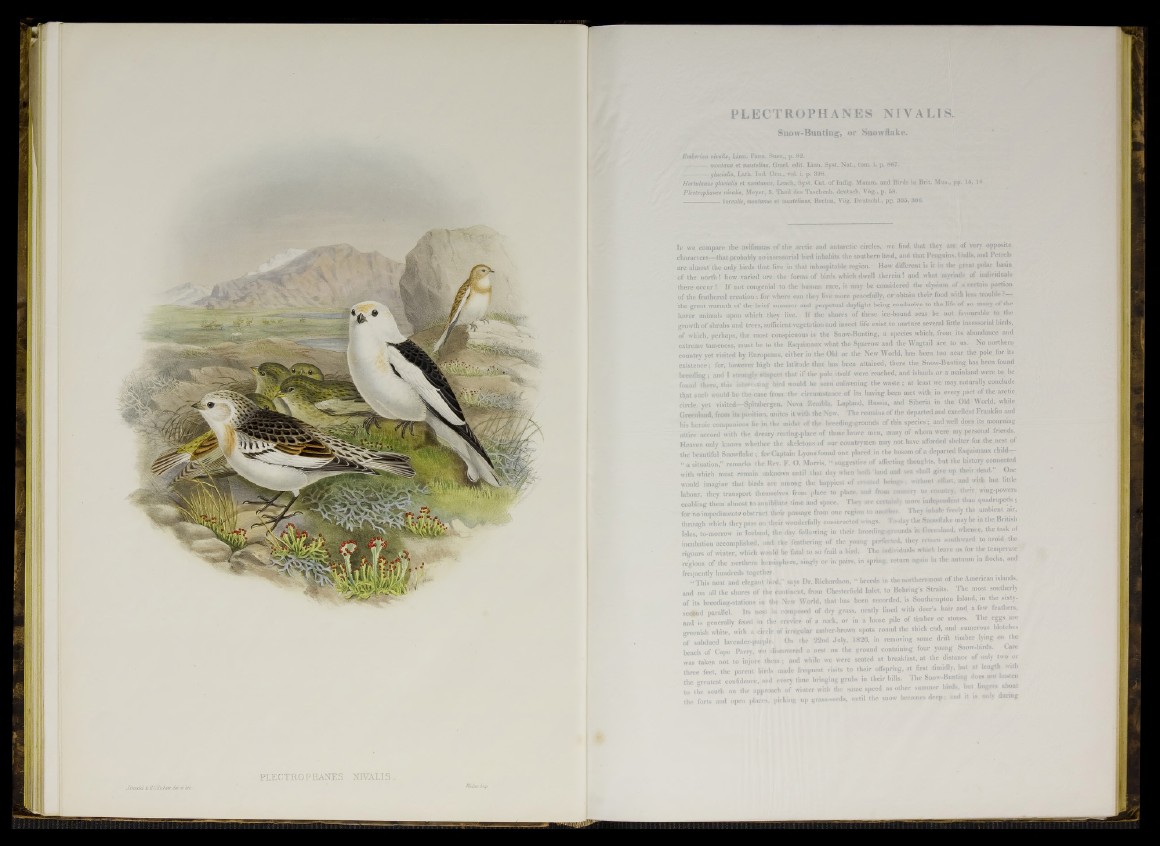

PLECTROPHANES NIVALIS.

Snow-Bunting-, or Snowflake.

Emberiza nivalis, Linn. Faun. Suec., p. 82.

montana et mustelina, Gtnel. edit. Linn. Syst. Nat., torn. t. p. 867.

glacialis, Lath. Ind. Orn., vol. i. p. 398.

Hortulmus glacialis et mania«««, Leach, Syst. C at of Indig. Hamm, and Birds in Brit. Mus., pp. 15, 16.

Pleclropbanes nivalis, Meyer, 3. Thcil des Taechenb. deutsch. Vög., p. 58.

/ — borealis,montanus et mustelinus, Brehm, Vög. Deutsch!., pp. 305,306.

Ip. we compare the avifaunas of the arctic and antarctic circles, we find, that they are of very opposite

characters—that probably no inscssorial bird inhabits the southern land, and that Penguins, (nulls, and Petrels

are almost the only birds that live in that inhospitable regiou. How different is it in the great polar basin

of the north! how varied are. the forms of birds which dwell therein! and what myriad» of individuals

there occur I If not congenial to the human race, it may be considered the elysiom of a certain portion

of the feathered creation: for where can they live-tnore peacefully, or obtain their food with, less trouble ?

the great warmth of the brief summer and perpetual daylight being conducive to the life of so many of the

lower animals upon which they live. If the shores of these ice-bound seas be not favourable to the

growth of shrubs and trees, sufficient vegetation aud insect life exist to nurture several little insessorial birds,

of which, perhaps, the most conspicuous is the Snow-Bunting, a species which,.from its abundauce and

extreme tameness, must be to the Esquimaux what the Sparrow and the Wagtail are to us. No northern

country yet visited by Europeans, either in the Old or the. New World, has been too near the pole for its

existence; for, however high the latitude that has been attained, there the Snow-Bunting has been found

breeding; and I strongiv suspect that if the pole itself were reached, and islands or a mniuland were to be

found there, this interesting bird would be seen enlivening the waste ; at least we may naturally conclude

that such would be the case from the circumstance of its having been met with in every part of the arctic

circle yet visited—Spitsbergen, Nova Zembta. Lapland, Russia, and Siberia in the Old World, while

Greenland, from its position, unites it with the New. The remains of the departed and excellent Franklin and

his heroic companions lie in the midst of the breeding-grounds of this species; and well does its mourning

attire accord with the dreary resting-place of those brave men, many of whom were my personal friends.

Heaven only knows whether the skeletons of our countrymen may not have afforded shelter for the nest of

the beautiful Snowffake ; for Captain Lyons found one placed in the bosom of a departed Esquimaux child—

“ a situation,” remarks the Rev. F. O. Morris, " suggestive of affecting thoughts, but the history connected

with which must remain unknown until that day when both land and sea shall give up their dead. One

would imagine that birds are among the happiest of created being : without effort, and u ith but little

labour, they transport themselves from place to place, and from coal,try to country, their wing-powers

enabling them almost to annihilate time and space. They are ccrtomt« more independent than quadrupeds ;

for no impediments obstruct their passage from one region to another. They inhale freely the ambient air,

through which they pass on their wonderfully constructed rings. To-day the Snowflake may be in the British

Isles, to-morrow in Iceland, the day following in their breeding-grounds in Greenland, whence, the task of

incubation accomplished, and the feathering of the young perfected, they return southward to avoid the

rigours of winter, which would be fatal to so frail a bird. The individuals which leave us for the temperate

regions of the northern hemisphere; singly or in pairs, in spring, return again in the autumn in flocks, and

frequently hundreds together. . .

.. This neat and elegant bird," says Hr. Richardson, “ breeds in the northernmost of the American islands,

and on all the shores of the continent, from Chesterfield Inlet, to Behring's Straits. The most southerly

of its breeding-stations in the New World, that has been recorded, is Southampton Island, m the sixty-

second parallel. Its nest is composed of dry grass, neatly lined with deer’s hair and a few feathers,

and is generally fixed in the crevice of a rock, or in a loose pile of timber or stones. The eggs are

greenish white, with a circle of irregular umber-brown spots round the thick end, and numerous blotches

of subdued lavender-purple. On the 22nd July, 1828, in removing some drift timber lying on the

beach of Cape Parry, we discovered a nest on the ground containing four young Suow-birds. Care

was taken not to injure them ; and while we were seated at breakfast, at the distance of only two or

three feet, the parent birds made frequent visits to their offspring, at first timidly, but at length with

the greatest confidence, and every time bringing grubs in their bills. The Snow-Bonting does not

listen

to the south on the approach of winter with the same speed as other summer bird:

:s about

t h e fo r t s and o p e n places, p ic k in g u p gra is-seeds, until the snow becomes deep; an«

' during