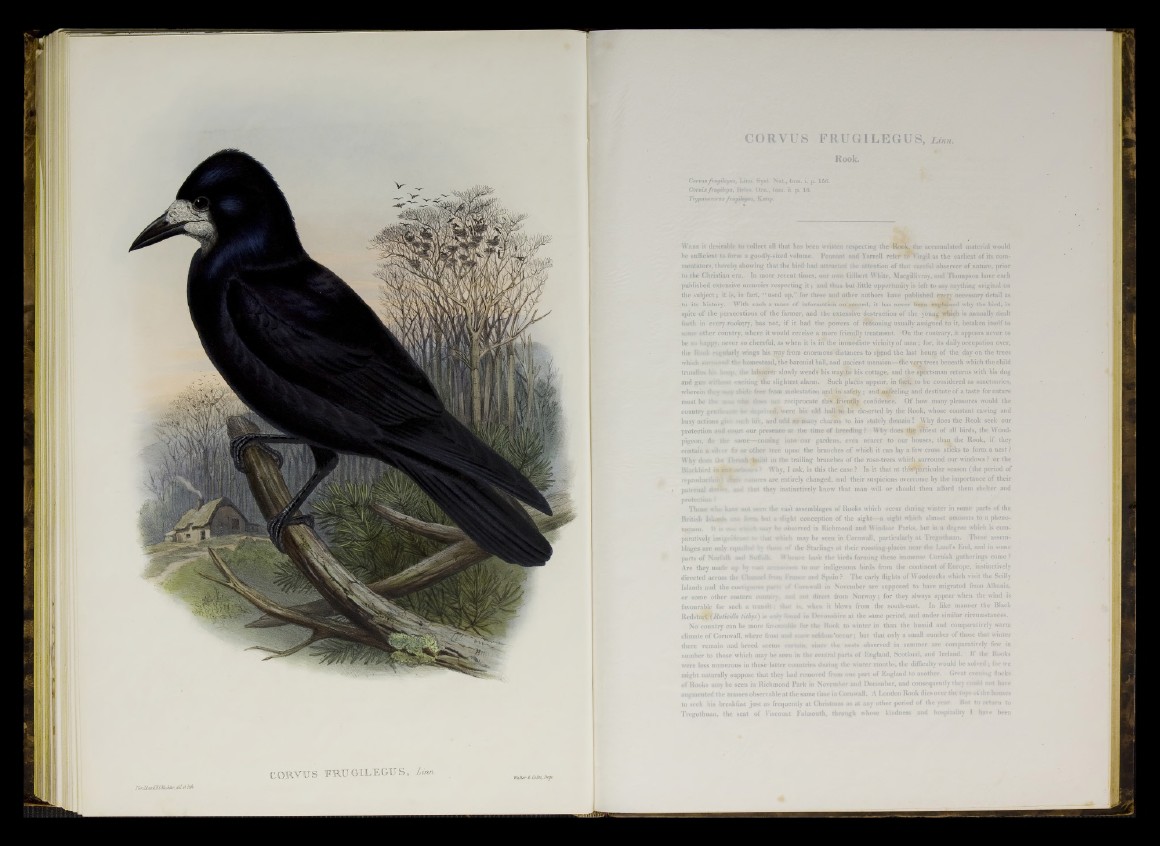

CO B .VU S F K U G IL E G U S , Linn. VaZUr / CoJui, Tmji.

Rook.

Gorvus.frugikgus, Linn. Syst. Nat., tom. i. p. 156.

Comixfrugilega, Brisis. Oru., tfim. ii. p. 16.

Trypanocorax fntgUerftis, Kaup.

Were it desirable to collect all that has been written respecting the Rook, the accumulated material would

be sufficient to form a goodly-sized volume. Pennant and Yarrell refertoVirgil as the earliest of its commentators,

thereby showing that the bird had attracted the attention of that careful observer of nature, prior

to the Christian era. In more recent times, our own Gilbert White, Macgillivray, and Thompson have each

published extensive memoirs respecting i t ; and thus but little opportunity is left to say anything original on

the subject; it is, in fact, “ used up,” for these and other authors have published e v e ry necessary detail as

to its history. With such a mass of information on; record, it has never been explained why the bird, in

spite of the persecutions of the farmer, and the extensive destruction of the young which is annually dealt

forth in every rookery, has not, if it had the powers of reasoning usually assigned to it, betaken itself to

seme other country, where it would receive a more friendly treatment. On the. contrary, it appears never to

be so happy* never so cheerful, as when it is in the immediate vicinity of man; for, its daily occupation over,

the U‘> regularly wings his way from enormous^distances to spend the last hours of the day on the trees

which s the homestead, the baronial ball, and ancient mansion—the very trees beneath which the child

trundles hi- . the labourer slowly wends his way;:to his cottage» and the sportsman returns with his dog

and go» without exciting the slightest alarm. Such places appear, in feet, to be considered as sanctuaries,

wlierein they way abide free from molestation and in safety; and-unfeeling and destitute of a taste for nature

mast be ih*c -*•*& jw s not reciprocate this friendly confidence. Of how .many pleasures would the

country gen.. fee deprived, were his old hall to be deserted by the Rook, whose constant cawing and

busy actions give life, and add somany charms to his stately domain ! Why does the Rook seek our

protection and court our presence at the time of. breeding ? Why does the shiest of all birds, the Wood-

pigeon, do the same—coming iuto our gardens, even nearer to our houses, thau the Rook, if they

contain a nfteer fir or other tree upon the brauches of which it can lay a few cross sticks to form a nest ?

Why docs the i.-ab lailhl in the trailing branches of the rose-trees which, surround our windows ? or the

Blackbird in cdr ? Why, I ask, is this the case ? Is it that at this^articular season (the period of

reproduction} «atitres are entirely changed, and their suspicions overcome by the importance of their

paternal d - .vmi that they instinctively know that man will or should then afford them shelter and

Those who have not seen the vast assemblages of Rooks which occur during winter in some parts of the

British IsU-sjxfe mm form but a slight conception of the sight—a sight which almost amounts to a phenomenon.

It » <*** may be observed in Richmond and Windsor Parks, but in a degree which is comparatively

insigftiftewtt* I« (hat which may be seen in Cornwall, particularly at Tregothnan. These assemblages

are only equalled by those of the Starlings at their roosting-places near the Land's End, and in some

parts of Norfolk and Suffolk. W hence have the birds forming these immense Cornish gatherings come ?

Are they made up hr vast ¿a . to our indigenous birds from the continent of Europe, instinctively

directed across the Channel from France and Spain ? The early flights of Woodcocks which visit the Scilly

Islands and the contiguous parts - t Com wall in November are supposed to have migrated from Albania,

or some other eastern country. aod not direct from Norway; for they always appear when the wind is

favourable for such a transit. that is, when it blows from the south-east. In like manner the Black

R e d s ta rtRuticilla tithys) is only found in Devonshire at the same period, and under similar circumstances.

No'country can be more favourable for the Rook to winter in than the humid and comparatively warm

climate of Cornwall, where frost and snow seldom'occur; hut that only a small number of those that winter

there remain and breed seems certain, since the nests observed' in summer are comparatively few in

number to those which may be seen in the central parts of England, Scotland, and Ireland. If the Rooks

were less numerous in these latter countries during the winter months, the difficulty would be solved ; for we

might naturally suppose that they had removed from one part of England to another. Great evening flocks

of Rooks may be seen in Richmond Park in November and December, and consequently they could not have

augmented the masses observable at the same time in Cornwall. A London Rook flies over the tops of the houses

to seek his breakfast just as frequently at Christmas as at any other period of the year. But to return to

Tregothnan, the seat of Viscount Falmouth, through whose kindness and hospitality 1 have been