hop. At times it was impatient of confinement, and evinced an anxiety to escape from its cage, but was

not at all afraid of any one it was accustomed to. Being let out into a room 011 the 17th, it endeavoured

to get through the glass of the window. About the middle of August it would peck at a caterpillar, and

seemed particularly partial to the larvae of the Buff-tipped Moth (H. bucephala), which it generally passed

through the bill, holding them by the extremities and shaking before eating them. In the third week of

September it became very restless in the early part of the night, and occasionally, when it was moonlight,

endeavoured to get through the window. On the 29th of October it was still restless, but continued to be

fed by hand. On several evenings about the middle of November, during candle-light, it would flap its

wings and fall or flutter off its perch, occasionally uttering cue. It became much more contented about the

23rd of November, and the migratory instinct seemed to be succeeded by extreme voracity: its plumage

now much resembled that of the Woodcock. On the 28th, between nine and ten o’clock, it again became

restless. On the 3rd of December it was quite quiet. About the 25th of January, 1859, it began to moult,

and was still restless at times duriug the early part of the night, as it had been more or less ever since it

was able to fly. On the 7th of February it pecked at and ate some small pieces of meat and yelk, of

egg. In the beginning of the second week of this month, some of the fibrous ends of the new feathers

were exposed. During candle-light of the evening of the 12th, it uttered a loud shrill noise resembling

the laughing-note of the Green Woodpecker; by the middle of the month it became much less restless;

some of the new feathers appeared on the back, and it generally fed itself by taking meat with egg, or meat

alone, from my hand or the bars of the cage, sometimes descending to the bottom to pick up pieces that

had fallen. By the end of the second week in March, much of the new plumage appeared on its back aud

breast; but many old feathers still remained on the wing, at the back of the head, and on the upper part of

the breast. Black beetles (Blatta), to which it evinced a decided partiality, and meat with egg now

constituted its chief food. It was still restless at times, and on the 16th of April made a loud noise. On

the 28th I gave it a dead mouse, which it appeared to regard as an edible article, for it took it in its bill

and shook it several times. On my taking it to pieces, it ate some of the skin, fur, bones, and flesh. It

had not yet changed all its wing-feathers. On the 15th of May it called ‘ Cuckoo.’ On the 28th of July

it was observed to drink for the first time. Unfortunately I did not record the date of my bird’s death; but

it was alive on the 28th of July; I therefore kept it for more than twelve months. It was tame with those

to whom it was accustomed, but became pugnacious when teased with the finger, and would occasionally

peck at it with raised wings and the utterance of a loud noise. It would sometimes plume its feathers, and

was fond of being placed in the sunshine, when it would droop its wings and appear to greatly enjoy the

heat. It was very capricious with regard to its food, sometimes eating much raw meat and many black

beetles, of which it would devour several in succession, while at others it would eat very little; .after eating;

it would often wipe its bill. If the top of its cage were uncovered, it would occasionally fly upwards and

cling to the band of osiers running across between the dome of the cage and the part whence it sprang, and

then fall to the bottom. It had a very curious habit of snapping its bill and shaking its head when I spoke

to i t ; but this was not invariably done. When a cat or any unusual object attracted its attention, it would

stretch out its neck, depress the tail-feathers, and anxiously watch the object. I never observed it cast up

any portion of what it had eaten, in the manner of Hawks and Owls, not even the fur of the mouse mentioned

above. For months it was never seen to drink, but was sometimes given water from the finger or stick;

and the paste of egg and meat, or bread and egg, had usually water put with it. It was a male bird, and

had two white spots on the head before its first moult.”

The food of the Cuckoo consists of insects of various kinds, particularly in their larva or caterpillar state;

for these it searches the lofty branches of the trees, over which it climbs and clings like a Parrot; it also

descends to the grassy meads for moths, grasshoppers, and Coleoptera.

The sexes of the Cuckoo, when fully adult, are very similar; sometimes, however, the female is more or

less diversified with brown. The young bird, during the first autumn, resembles the Woodcock in its general

colouring; but in some instances the ground-colour is white, as in the adult. When about three parts

fledged, it is a squat object, with a short stumpy tail, the feathers of which are about an inch in length, and

tipped with snow-white; those of the head and body are dark blackish grey, with crescentic markings of

greyish white at the tips of the feathers; in some instances the breast and under surface are white, barred

with blackish grey, as in the adult; there are no brown markings except on the scapularies ; the eye is deep-

sunken, and of a blackish-brown hue, with a narrow dark olive-coloured lash; the bill and the round

swollen nostrils mealy olive; corners of the mouth narrowly edged with orange, inside of the mouth bright

fiery orange; legs and toes delicate fleshy white.

Cuckoos are occasionally found in Europe in spring, still wearing the livery of the nestling. This has

caused several naturalists to fall into the error of supposing they were another species.

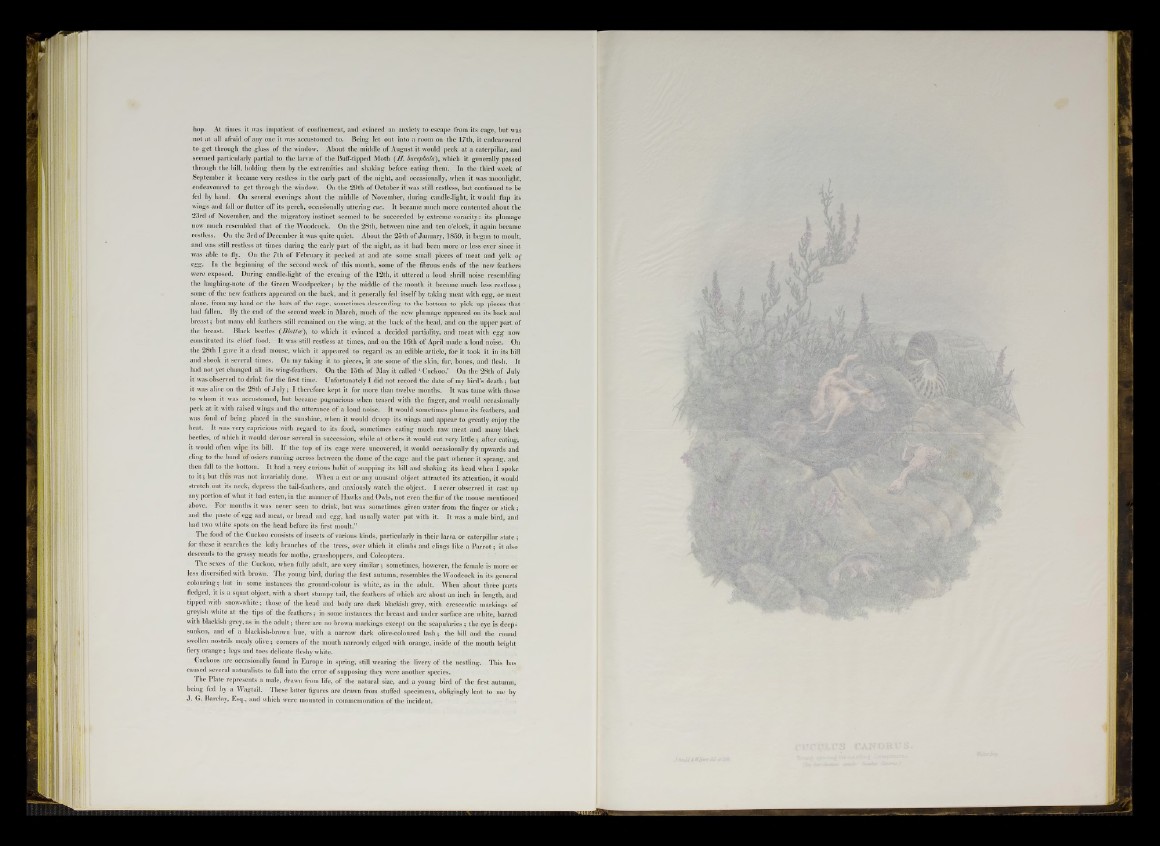

The Plate represents a male, drawn from life, of the natural size, and a young bird of the first autumn,

being fed by a Wagtail. These latter figures are drawn from stuffed specimens, obligingly lent to me by

J . G. Barclay, Esq., and which were mounted in commemoration of the incident.