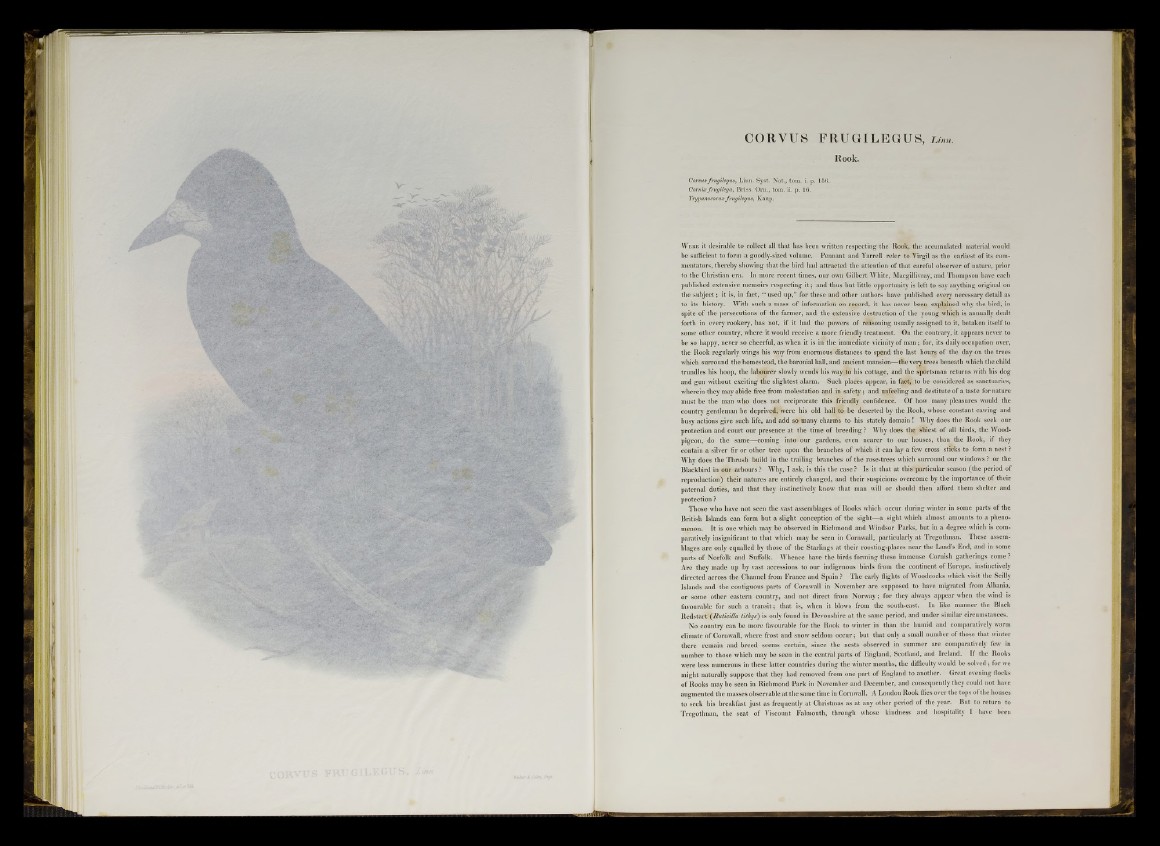

CORVUS FRUGILEGUS, Linn.

Kook.

Corvus frugilegus, Linn. Syst. Nat., tom. i. p. 156.

Cornix frugilega, Briss. Orn., tom. it. p. 16.

Trypanocorax frugilegus, Kaup.

W e r e it desirable to collect all that has been written respecting the Rook, the accumulated material would

be sufficient to form a goodly-sized volume. Pennant and Yarrell refer to Virgil as the earliest of its commentators,

thereby showing that the bird had attracted the attention of that careful observer of nature, prior

to the Christian era. In more recent times, our own Gilbert White, Macgillivray, and Thompson have each

published extensive memoirs respecting it ; and thus but little opportunity is left to say anything original on

the subject ; it is, in fact, “ used up,” for these and other authors have published every necessary detail as

to its history. With such a mass of information on record, it has never been explained why the bird, in

spite of the persecutions of the farmer, and the extensive destruction of the young which is annually dealt

forth in every rookery, has not, if it had the powers of reasoning usually assigned to it, betaken itself to

some other country, where it would receive a more friendly treatment. On the contrary, it appears never to

be so happy, never so cheerful, as when it is in the immediate vicinity of man ; for, its daily occupation over,

the Rook regularly wings his way from enormous "distances to spend the last hours of the day on the trees

which surround the homestead, the baronial hall, aud ancient mansion—the very trees beneath which the child

trundles his hoop, the labourer slowly wends his way to his cottage, and the sportsman returns with his dog

and gun without exciting the slightest alarm. Such places appear, in fact,i. to be considered as sanctuaries,

wherein they may abide free from molestation and in safety ; and unfeeling and destitute of a taste for nature

must be the man who does not reciprocate this friendly confidence. Of how many pleasures would the

country gentleman be deprived; were his old hall to he deserted by the Rook, whose constant cawing and

busy actions give such life, and add so many charms to his stately domain ! Why does the Rook seek our

protection and court our presence at the time of breeding ? Why does the shiest of all birds, the Wood-

pigeon, do the same—coming into our gardens, even nearer to our houses, than thé Rook, if they

contain a silver fir or other tree upon the branches of which it can lay a few cross sticks to form a nest ?

Why does the Thrush build in the trailing branches of the rose-trees which surround our windows ? or the

Blackbird in our arbours ? Why, I ask, is this the case ? Is it that at this particular season (the period of

reproduction) their natures are entirely changed, and their suspicions overcome by the importance of their

paternal duties, and that they instinctively know that man will or should then afford them shelter and

protection ?

Those who have not seen the vast assemblages of Rooks which occur during winter in some parts of the

British Islands can form but. a slight conception of the sight—a sight which almost amounts to a phenomenon.

It is one which may be observed in Richmond and Windsor Parks, but in a degree which is comparatively

insignificant to that which may be seen in Cornwall, particularly at Tregothnan. These assemblages

are only equalled by those of the Starlings at their roosting-places near the Land’s End, and in some

parts of Norfolk and Suffolk. Whence have the birds forming these immeuse Cornish gatherings come ?

Are they made up by vast accessions to our indigenous birds from the continent of Europe, instinctively

directed across the Channel from France and Spain ? The early flights of Woodcocks which visit the Scilly

Islands and the contiguous parts of Cornwall in November are supposed to have migrated from Albania,

or some other eastern country, and not direct from Norway ; for they always appear when the wind is

favourable for such a transit; that is, when it blows from the south-east. In like manner the Black

Redstart'(RuticiUa tithys) is only found in Devonshire at the same period, and under similar circumstances.

No country can be more favourable for the Rook to winter in than the humid and comparatively warm

climate of Cornwall, where frost and snow seldom occur ; but that only a small number of those that winter

there remain and breed seems certain, since the nests observed in summer are comparatively few in

number to those which may be seen in the central parts of England, Scotland, and Ireland. If the Rooks

were less numerous in these latter countries during the winter months, the difficulty would be solved ; for we

might naturally suppose that they had removed from one part of England to another. Great evening flocks

of Rooks may be seen in Richmond Park in November and December, and consequently they could not have

augmented the masses observable at the same time in Cornwall. A London Rook flies over the tops of the houses

to seek his breakfast just as frequently at Christmas as at any other period of the year. But to return to

Tregothnan, the seat of Viscount Falmouth, through whose kindness and hospitality I have been