orifice of the ear, is a large and elongated parotid gland, from which a membranous duct passes as fcir

forward as the point of union of the two bones forming together the lower mandible, on the inner surface

of which the glutinous secretion of these large glands passes out, and may he seen to issue, on making slight

pressure along the course of the glands. The flattened inner surface of the two bones, which are united

along the distal part of their lower edge, forms the natural situation of the tongue when at rest within the

mandibles; and every time it is drawn into the mouth, when the bird is feeding, it becomes covered with a

fresh supply of the glutinous mucus. From a close examination of the stomachs of many specimens, 1 am

induced to believe that the point of the tongue is not used as a spear, nor the food taken up by the beak,

unless it be too heavy to be lifted by adhesion.

“ Insects of various sorts, ants and their eggs, form the principal food; and I have seldom examined a

recently-killed specimen the beak of which did not indicate, by the earth adhering to the base and to the

feathers about the nostrils, that the bird had been at work at an ant-hill.

“ The Green Woodpecker inhabits holes in trees, which it excavates or enlarges for its use, chiefly in the

elm or the ash, in preference to those of harder wood. When excavating a hole in a tree for the purpose

of incubation, the birds, it is said, will carry away the chips to a distance, in order that they may not lead

to the discovery of their retreat, as other birds are known to carry away the egg-shells and the mutings of

their young. It makes no nest, but deposits its eggs on the loose, soft fragments of the decayed wood.

The eo-gs are from five to seven in number, smooth, shining, and pure white, 1 inch 2 ! lines in length by

] 0 | lines in breadth. The young birds are fledged in June, and creep about the tree a short distance from

the hole before they are able to fly. I have known the young birds to be taken from the tree and brought

up by hand, becoming very tame, and giving utterance to a low note, not unlike that of a very young

gosling. The adult birds also make a low jarring sound, which is supposed to be the call-note of sexes to

each other. Their more common note is a loud sound which has been compared to a laugh, and they are

said to be vociferous when rain is impending,—hence their name of Rain-bird; and as it is highly probable

that no change takes place in the weather without some previous alteration in the electrical condition of

the atmosphere, we can easily understand that birds, entirely covered as they are with feathers, which are

known to he readily affected by electricity, should be susceptible of certain impressions, which are indicated

by particular actions: thus birds and other animals, covered only with the production of their highly sensible

skin, become living barometers to good observers.”

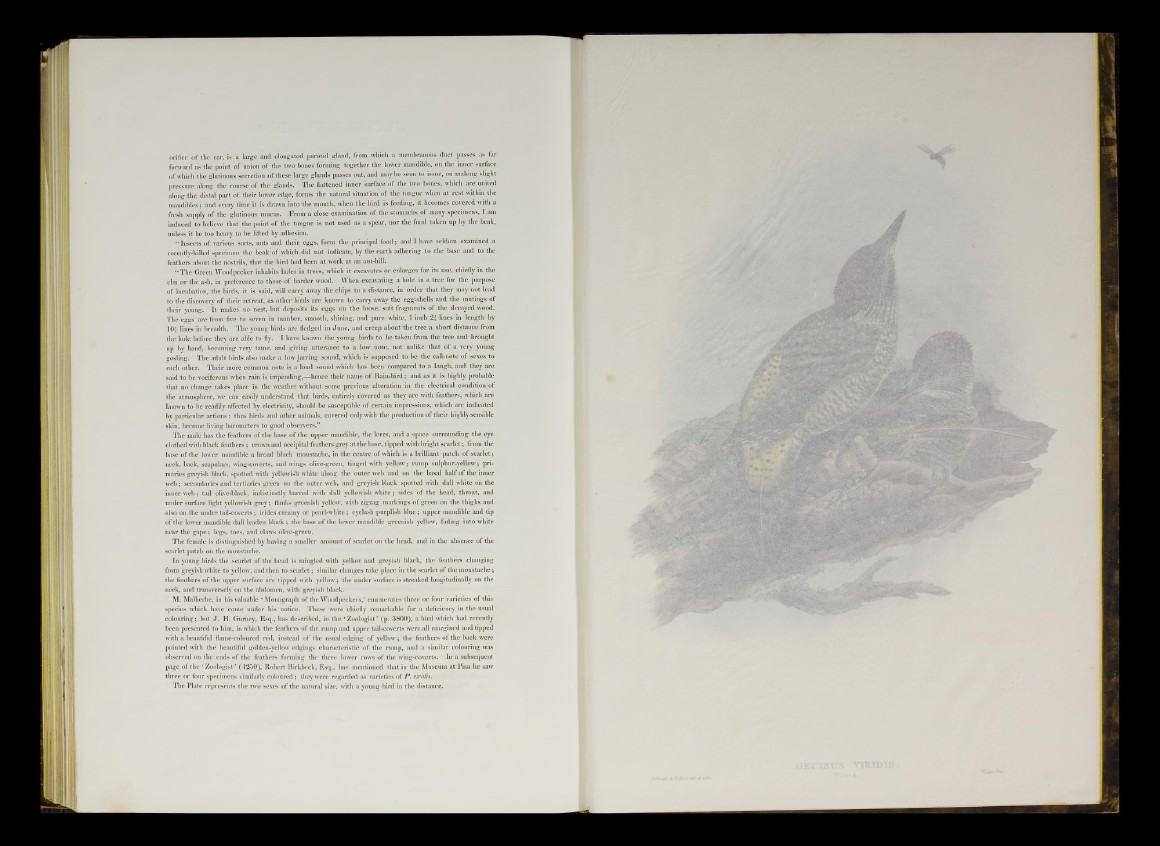

The male has the feathers of the base of the upper mandible, the lores, and a space surrounding the eye

clothed with black feathers; crown and occipital feathers grey at the base, tipped with bright scarlet; from the

base of the lower mandible a broad black moustache, in the centre of which is a brilliant patch of scarlet;

neck, back, scapulars, wing-coverts, and wings olive-green, tinged with yellow; rump sulphur-yellow; primaries

greyish black, spotted with yellowish white along the outer web and on the basal half of the inner

web; secondaries and tertiaries green on the outer web, and greyish black spotted with dull white on the

inner web; tail olive-black, indistinctly barred with dull yellowish white; sides of the head, throat, and

under surface light yellowish grey; flanks greenish yellow, with zigzag markings of green on the thighs and

also on the under tail-coverts; irides creamy or pearl-white; eyelash purplish blue; upper mandible and tip

of the lower mandible dull leaden black ; the base of the lower mandible greenish yellow, fading into white

near the gape; legs, toes, and claws olive-green.

The female is distinguished by having a smaller amount of scarlet on the head, and in the absence of the

scarlet patch on the moustache.

In young birds the scarlet of the head is mingled with yellow and greyish black, the feathers changing

from greyish white to yellow, and then to scarlet; similar changes take place in the scarlet of the moustache;

the feathers of the upper surface are tipped with yellow; the under surface is streaked longitudinally on the

neck, and transversely on the abdomen, with greyish black.

M. Malherbe, in his valuable ‘ Monograph of the Woodpeckers,’ enumerates three or four varieties of this

species which have come under his notice. These were chiefly remarkable for a deficiency in the usual

colouring; but J. H. Gurney, Esq., has described, in the ‘Zoologist’ (p. 3800), a bird which had recently

been presented to him, in which the feathers of the rump and upper tail-coverts were all margined and tipped

with a beautiful flame-coloured red, instead of the usual edging of yellow; the feathers of the hack were

pointed with the beautiful golden-yellow edgings characteristic of the rump, and a similar colouring was

observed on the ends of the feathers forming the three lower rows of the wing-coverts. In a subsequent

page of the ‘ Zoologist ’ (4250), Robert Birkbeck, Esq., has mentioned that in the Museum at Pisa he saw

three or four specimens similarly coloured ; they were regarded as varieties of P. viridis.

The Plate represents the two sexes of the natural size, with a young bird in the distance.