§ s p

PICA CAUDATA.

Magpie.

Corvtis pica, Linn. Faun. Suec., No. 92.

Pica caudata, Linn. Syst. Nat., edit. 6, gen. 40, sp. 8.

— Europaa, Cuv.

Melanoleuca, Vieill. Ency. Meth. Om., part 2. p. 883, pi. 139. fig. 1 .

I t r u s t the day may arrive when the people of this country will have acquired a greater taste for the

ornamental than at present; they may then have their eyes opened to the charms of that one of our native

birds in which is combined all that is graceful and elegant in form and beautiful in colouring: 1 mean the

British Magpie—the Magot Pie of the immortal Shakspeare. For my own part, I never see this bird in a

state of nature without a feeling of admiration. I watch all its actions with interest and pleasure. I do

not fail to notice how its varied plumage contrasts with the greensward over which it walks, and, when it is

flying towards a coppice or tree, with what regularity and precision its wings are marked with black and white.

I also admire its pertness, and the elegance of its actions among the branches. I observe how in this country

it sedulously avoids man, and particularly the keeper of game, while he walks, gun in hand, his daily

rounds; while in others, such as Norway and Sweden, it is just as familiar in the approaches it makes

to the gardens and to the houses, to the roofs of which it flies for protection, if protection be necessary.

How fortunate, then, are the Magpies of those countries, and of France, where they are similarly treated!

Surely this will awaken some of our landed proprietors to the necessity of at least in some degree rendering

its existence here a more happy one.

If Mr. Waterton can keep the Magpie within proper bounds, and find that its propensities are not fatal

to the reproduction of other birds within his walled demesne, and if Sir William Jardine (who, I know,

affords it his protection), has not’ his Pheasants’ eggs destroyed, or his garden ravaged of its summer

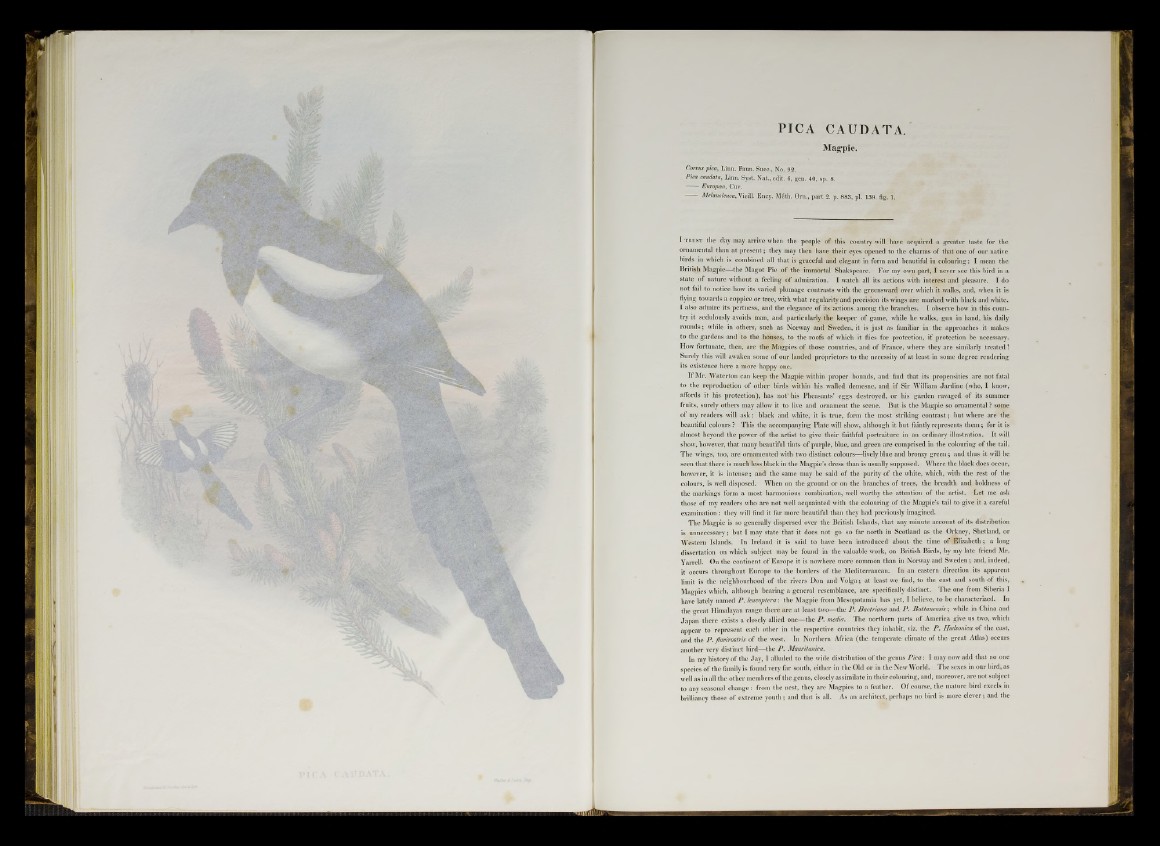

fruits, surely others may allow it to live and ornament the scene. But is the Magpie so ornamental ? some

of my readers will ask: black and white, it is true, form the most striking contrast; but where are the

beautiful colours ? This the accompanying Plate will show, although it but faintly represents them; for it is

almost beyond the power of the artist to give their faithful portraiture in an ordinary illustration. It will

show, however, that many beautiful tints of purple, blue, and green are comprised in the colouring of the tail.

The wings, too, are ornamented with two distinct colours—lively blue and bronzy green; and thus it will be

seen that there is much less black in the Magpie’s dress than is usually supposed. Where the black does occur,

however, it is intense; and the same may be said of the purity of the white, which, with the rest of the

colours, is well disposed. When on the ground or on the branches of trees, the breadth and boldness of

the markings form a most harmonious combination, well worthy the attention of the artist. Let me ask

those of my readers who are not well acquainted with the colouring of the Magpie’s tail to give it a careful

examination : they will find it far more beautiful than they had previously imagined.

The Magpie is so generally dispersed over the British Islands, that any minute account of its distribution

is unnecessary; but I may state that it does not go so far north in Scotland as the Orkney, Shetland, or

Western Islands. In Ireland it is said to have been introduced about the time of Elizabeth; a long

dissertation on which subject may be found in the valuable work, on British Birds, by my late friend Mr.

Yarrell. On the continent of Europe it is nowhere more common than in Norway and Sweden; and, indeed,

it occurs throughout Europe to the borders of the Mediterranean. In an eastern direction its apparent

limit is the neighbourhood of the rivers Don and Volga; at least we find, to the east and south of this,

Magpies which, although bearing a general resemblance, are specifically distinct. The one from Siberia I

have lately named P. leucoptera: the Magpie from Mesopotamia has yet, I believe, to be characterized. In

the great Himalayan range there are at least two—the P. Bactriana and P. Bottanensis; while in China and

Japan there exists a closely allied one—the P. media. The northern parts of America give us two, which

appear to represent each other in the respective countries they inhabit, viz. the P. Hudsonica of the east,

and the P. flavirostris of the west. In Northern Africa (the temperate climate of the great Atlas) occurs

another very distinct bird—the P. Mauritania.

In my history of the Jay, I alluded to the wide distribution of the genus Pica: I may now add that no one

species of the family is found very far south, either in the Old or in the New World. The sexes in our bird, as

well as in all the other members of the genus, closely assimilate in their colouring, and, moreover, are not subject

to any seasonal change: from the nest, they are Magpies to a feather. Of course, the mature bird excels in

brilliancy those of extreme youth; and that is all. As an architect, perhaps no bird is more clever; and the