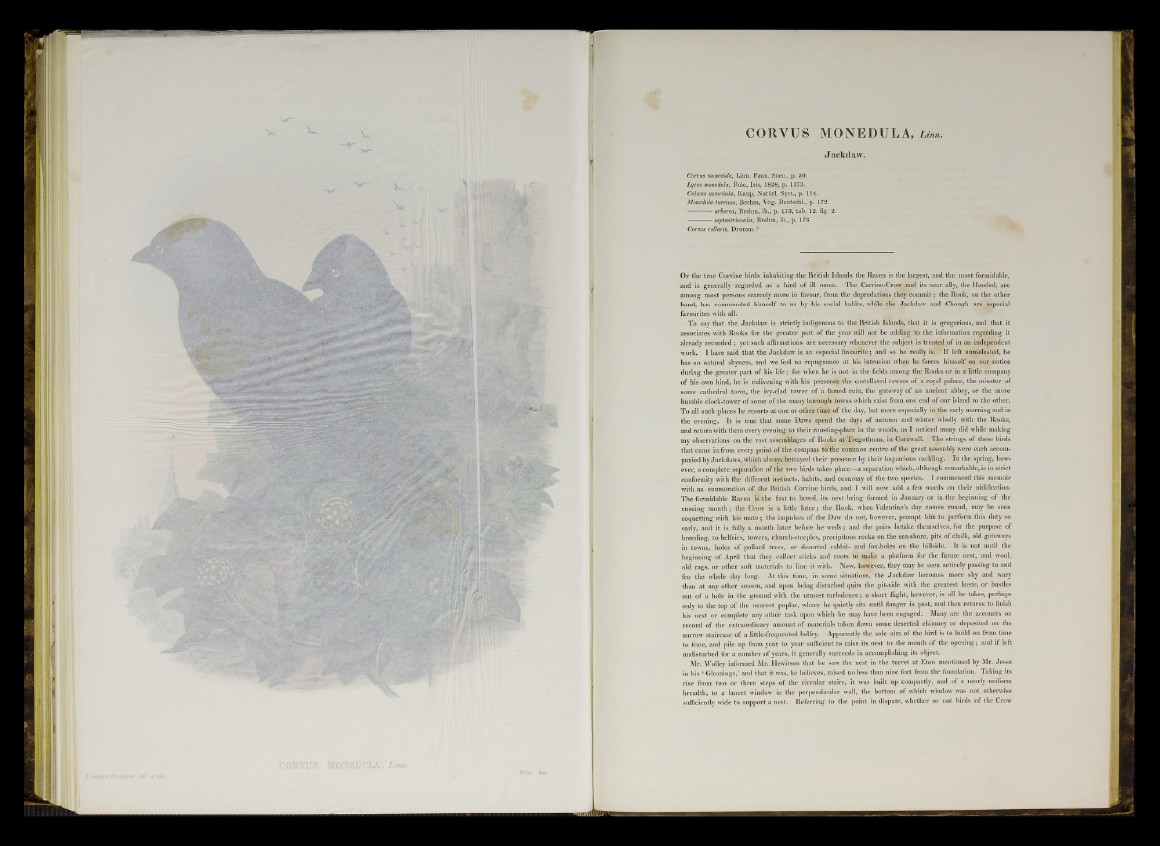

t v u s MOKEBBA,

J ackdaw.

Corvus monedula, Linn. Faun. Suec., p. 30.

Lycos monedula, Boie, Isis, 1828, p. 1273.

Colceus monedula, Kaup, Naturl. Syst., p. 114.

Monedula turrium, Brehm, Vog. Deutschl., p. 172.

---------- arborea, Brehm, ib., p. 173, tab. 12. fig. 2.

---------- septentrionalis, Brehm, ib., p. 173.

Corvus collaris, Drumm. ?

Of the true Corvine birds inhabiting the British Islands the Raven is the largest, and the most formidable,

and is generally regarded as a bird of ill omen. The Carrion-Crow and its near ally, the Hooded, are

among most persons scarcely more in favour, from the depredations they commit; the Rook, on the other

hand, has commended himself to us by his social habits, while the Jackdaw and Chough are especial

favourites with all.

To say that the Jackdaw is strictly indigenous to the British Islands, that it is gregarious, and that it

associates with Rooks for the greater part of the year will not be adding to the information regarding it

already recorded ; yet such affirmations are necessary whenever the subject is treated of in an independent

work. I have said that the Jackdaw is an especial favourite; and so he really is. ' If left unmolested, he

has no natural shyness, and we feel no repugnance at his intrusion when he forces himself on our notice

during the greater part of his life; for when he is not in the fields among the Rooks or in a little company

of his own kind, he is enlivening with his presence the castellated towers of a royal palace, the minster of

some cathedral town, the ivy-clad tower of a famed ruin, the gateway of an ancient abbey, or the more

humble clock-tower of some of the many borough towns which exist from one end of our island to the other.

To all such places he resorts at one or other time of the day, but more especially in the early morning and in

the evening. It is true that some Daws spend the days of autumn and winter wholly with the Rooks,

and return with them every evening, to their roosting-place in the woods, as I noticed many did while making

my observations on the vast assemblages of Rooks at Tregothnan, in Cornwall. The strings of these birds

that came in from every point of the compass to"the common centre of the great assembly were each accompanied

by Jackdaws, which always betrayed their presence by their loquacious cackling. In the spring, however,

a complete separation of the two birds takes place—a separation which, although remarkable, is in strict

conformity with the different instincts, habits, and economy of the two species. I commenced this memoir

with an enumeration of the British Corvine birds, and I will now add a few words on their nidification.

The formidable Raven is the first to breed, its nest being formed in January or in the beginning of the

ensuing month; the Crow is a little la te r; the Rook, wheu Valentine’s day comes round, may be seen

coquetting with his mate ; the impulses of the Daw do not, however, prompt him to perform this duty so

early, and it is fully a month later before he weds; and the pairs betake themselves, for the purpose of

breeding, to belfries, towers, church-steeples, precipitous rocks on the sea-shore, pits of chalk, old gateways

in towns, holes of pollard trees, or deserted rabbit- and fox-holes on the hillside. It is not until the

beginning of April that they collect sticks and roots to make a platform for the future nest, and wool,

old rags, or other soft materials to line it with. Now, however, they may be seen actively passing to and

fro the whole day long. At this time, in some situations, the Jackdaw becomes more shy and wary

than at any other season, and upon being disturbed quits the pit-side with the greatest haste, or bustles

out of a hole in the ground with the utmost turbulence; a short flight, however, is all he takes, perhaps

only to the top of the nearest poplar, where he quietly sits until danger is past, and then returns to finish

his nest or complete any other task upon which he may have been engaged. Many are the accounts on

record of the extraordinary amount of materials taken down some deserted chimney or deposited on the

narrow staircase of a little-frequented belfry. Apparently the sole aim of the bird is to build on from time

to time, and pile up from year to year sufficient to raise its nest to the mouth of the opening ; and if left

undisturbed for a number of years, it generally succeeds in accomplishing its object.

Mr. Wolley informed Mr. Hewitson that he saw the nest in the turret at Eton mentioned by Mr. Jesse

in his ‘ Gleanings,’ and that it was, he believes, raised no less than nine feet from the foundation. Taking its

rise from two or three steps of the circular stairs, it was built up compactly, and of a nearly uniform

breadth, to a lancet window in the perpendicular wall, the bottom of which window was not otherwise

sufficiently wide to support a nest. Referring to the point in dispute, whether or not birds of the Crow