!

.

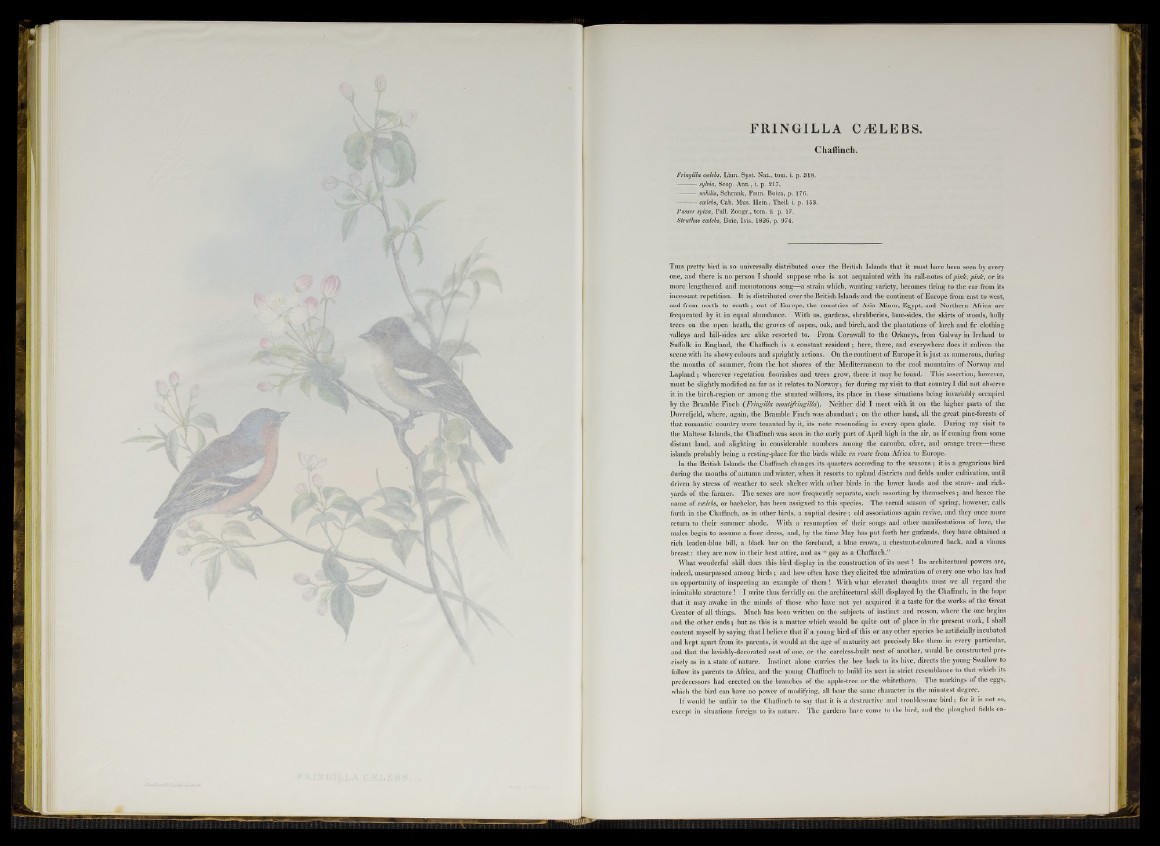

FRINGILLA CALEBS.

Chaffinch.

Fringilla Calebs, Linn. Syst. Nat., tom. i. p. 318.

sylvia, Scop. Ann., i. p. 217.

— nobilis, Schrank, Faun. Boica, p. 176.

ccelebs. Cab. Mus. Hein., Theil. i. p. 163.

Passer spiza, Pall. Zoogr., tom. ii p. 17.

Slruthus ccelebs, Boie, Isis, 1826, p. 974.

T h is pretty bird is so universally distributed over the British Islands that it must have been seen by every

one, and there is no person I should suppose who is not acquainted with its call-notes of pink, pink, or its

more lengthened and monotonous song—a strain which, wanting variety, becomes tiring to the ear from its

incessant repetition. It is distributed over the British Islands and the continent of Europe from east to west,

and from north to south; out of Europe, the countries of Asia Minor, Egypt, and Northern Africa are

frequented by it in equal abundance. With us, gardens, shrubberies, lane-sides, the skirts of woods, holly

trees on the open heath, the groves of aspen, oak, and birch, and the plantations of larch and fir clothing

valleys and hill-sides are alike resorted to. From Cornwall to the Orkneys, from Galway in Ireland to

Suffolk in England, the Chaffinch is a constant resident; here, there, and everywhere does it enliven the

scene with its showy colours and sprightly actions. On the continent of Europe it is just as numerous, during

the months of summer, from the hot shores of the Mediterranean to the cool mountains of Norway and

Lapland; wherever vegetation flourishes and trees grow, there it may be found. This assertion, however,

must be slightly modified as far as it relates to Norway; for during my visit to that country I did not observe

it in the birch-region or among the stunted willows, its place in those situations being invariably occupied

by the Bramble Finch (Fringilla montifringilla). Neither did I meet with it on the higher parts of the

Dovrefjeld, where, again, the Bramble Finch was abundant; on the other hand, all the great pine-forests of

that romantic country were tenanted by it, its note resounding in every open glade. During my visit to

the Maltese Islands, the Chaffinch was seen in the early part of April high in the air, as if coming from some

distant land, and alighting in considerable numbers among the carouba, olive, and orange trees—these

islands probably being a resting-place for the birds while en route from Africa to Europe.

In the British Islands the Chaffinch changes its quarters according to the seasons ; it is a gregarious bird

during the months of autumn and winter, when it resorts to upland districts and fields under cultivation, until

driven by stress of weather to seek shelter with other birds in the lower lands and the straw- and rick-

yards of the farmer. The sexes are now frequently separate, each assorting by themselves; and hence the

name of ccelebs, or bachelor, has been assigned to this species. The vernal season of spring, however, calls

forth in the Chaffinch, as in other birds, a nuptial desire; old associations again revive, and they once more

return to their summer abode. With a resumption of their songs and other manifestations of love, the

males begin to assume a finer dress, and, by the time May has put forth her garlands, they have obtained a

rich leaden-blue bill, a black bar on the forehead, a blue crown, a chestnut-coloured back, and a vinous

breast: they are now in their best attire, and as “ gay as a Chaffinch.”

What wonderful skill does this bird display in the construction of its nest! Its architectural powers are,

indeed, unsurpassed among birds; and how often have they elicited the admiration of every one who has had

an opportunity of inspecting an example of them! With what elevated thoughts must we all regard the

inimitable structure! I write thus fervidly on the architectural skill displayed by the Chaffinch, in the hope

that it may awake in the minds of those who have not yet acquired it a taste for the works of the Great

Creator of all things. Much has been written on the subjects of instinct and reason, where the one begins

and the other ends; but as this is a matter which would be quite out of place in the present work, I shall

content myself by saying that I believe that if a young bird of this or any other species be artificially incubated

and kept apart from its parents, it would at the age of maturity act precisely like them in every particular,

and that the lavishly-decorated nest of one, or the careless-built nest of another, would be constructed precisely

as in a state of nature. Instinct alone carries the bee back to its hive, directs the young Swallow to

follow its parents to Africa, and the young Chaffinch to build its nest in strict resemblance to that which its

predecessors had erected on the branches of the apple-tree or the whitethorn. The markings of the eggs,

which the bird can have no power of modifying, all bear the same character in the minutest degree.

It would be unfair to the Chaffinch to say that it is a destructive and troublesome bird; for it is not so,

except in situations foreign to its nature. The gardens have come to the bird, and the ploughed fields en