Ill

r

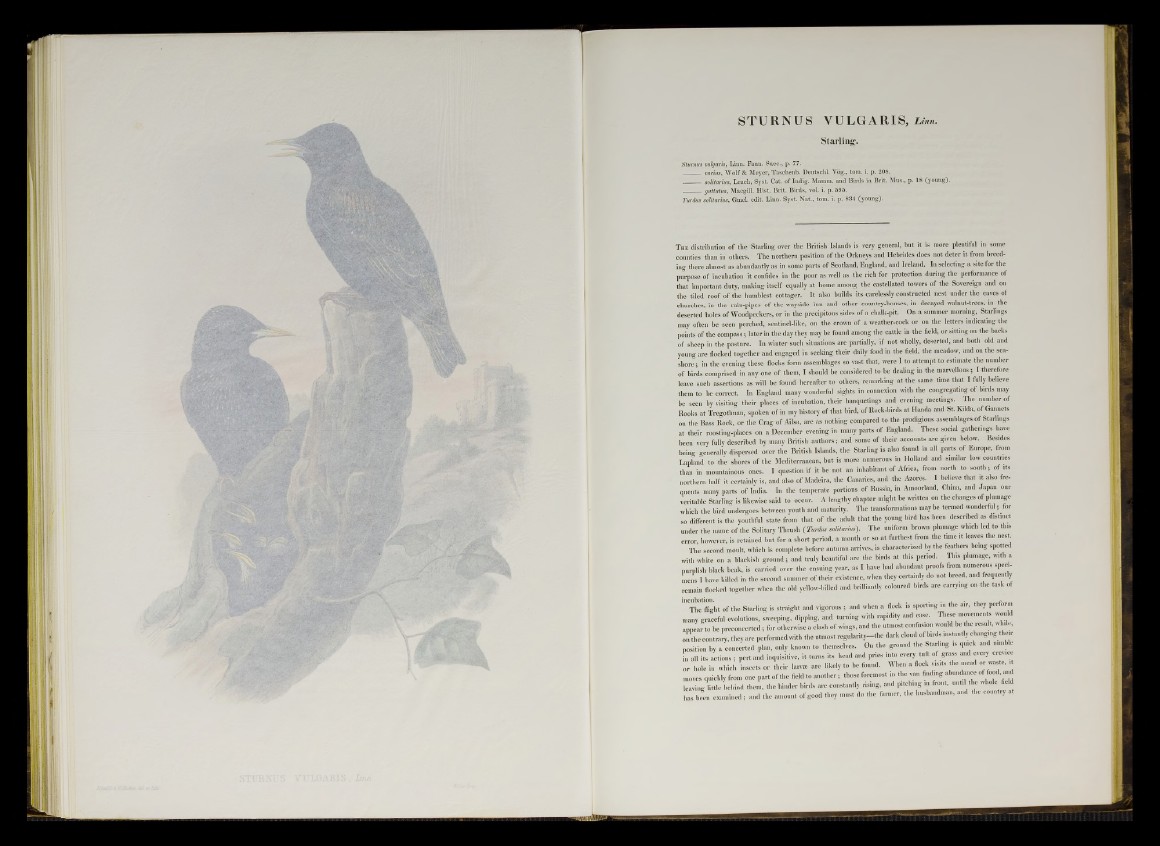

S T U R N U S V U L G A R I S , U m .

Starling’.

Stumus vulgaris, Linn. Faun. Suec., p. 77.

varius, Wolf & Meyer, Taschenb. Deutschi. Vög., tom. i. p. 208.

solitarius, Leach, Syst. Cat. of Indig. Mamm. and Birds in Brit. Müs,, p. 18 (young).

guttatiis, Macgill. Hist. Brit. Birds, vol. i. p. 595.

Turdus solitarius, Gmel. edit. Linn. Syst. Nat., tom. i. p. 834 (young).

T h e distribution of the Starling over the British Islands is very general, but it is more plentiful in some

counties than in others. The northern position of the Orkneys and Hebrides does not deter it from breeding

there almost as abundantly as in some parts of Scotland, England, and Ireland. In selecting a site for the

purpose of incubation it confides in the poor as well as the rich for protection during the performance of

that important duty, making itself equally at home among the castellated towers of the Sovereign and on

the tiled roof of the humblest cottager. It also builds its carelessly constructed nest under the eaves of

churches, in the rain-pipes of the wayside inn and other country-houses, in decayed walnut-trees, in the

deserted holes of Woodpeckers, or in the precipitous sides of a chalk-pit. On a summer morning, Starlings

may often be seen perched, sentinel-like, on the crown of a weather-cock or on the letters indicating the

points of the compass; later in the day they may be found among the cattle in the field, or sitting on the backs

of sheep in the pasture. In winter such situations are partially, if not wholly, deserted, and both old and

young are fiocked together and engaged in seeking their daily food in the field, the meadow, and on the seashore

; in the evening these flocks form assemblages so vast that, were I to attempt to estimate the number

of birds comprised in any one of them, I should be considered to be dealing in the marvellous; I therefore

leave such assertions as will he found hereafter to others, remarking at the same time that I fully believe

them to he correct. In England many wonderful sights in connexion with the congregating of birds may

be seen by visiting their places of incubation, their banqnetings and evening meetings. The number of

Books at Tregothnan, spoken of in my history of that bird, of Roek-birds at Handa and St. Kilda, of Gannets

on the Bass Bock, or the Crag of Ailsa, are as nothing compared to the prodigious assemblages of Starlings

at their roosting-places on a December evening in many parts of England. These social gatherings have

been very fully described by many British authors; and some of their accounts are given below. Besides

being generally dispersed over the British Islands, the Starling is also found in all parts of Europe, from

Lapland to the shores of the Mediterranean, but is more numerous in Holland and similar low countries

than in mountainous ones. I question if it be not an inhabitant of Africa, from north to south; of its

northern half it certainly is, and also of Madeira, the Canaries, and the Azores. I believe that it also frequents

many parte of India. In the temperate portions of Russia, in Amoorland, China, and Japan onr

veritable Starling is likewise said to occur. A lengthy chapter might be written on the changes of plumage

which the bird undergoes between youth and maturity. The transformations may be termed wonderful; for

so different is the youthful state from that of the adult that the young bird has been described as distinct

under the name of the Solitary Thrush (Turdus wlUarim). The uniform brown plumage which led to this

error, however, is retained but for a short period, a month or so at fbrtbest from the time it leaves the nest.

The second moult, which is complete before autumn arrives, is characterized by the feathers being spotted

with white on a blackish ground; and truly beautiful are the birds at this period. This plumage, with a

purplish black beak, is carried over the ensuing year, as I have had abundant proofs from numerous specimens

I have killed in the second summer of their existence, when they certainly do not breed, and frequently

remain flocked together when the old yellow-billed and brilliantly coloured birds are carrying on the task of

incubation. . . . . I H R

The flight of the Starling is straight and vigorous; and when a flock is sporting in e air, ey p r

many graceful evolutions, sweeping, dipping, and turning with rapidity and ease. These movements would

appear to be preconcerted; for otherwise a clash of wings, and the utmost confusion would be the result, while,

on the contmry, they are performed with the utmost regularity-the dark cloud of birds instantly changing their

position by a concerted plan, only known to themselves. On the ground the Starling ,s quick and nimble

h, all its actions ; pert and inquisitive, it turns its head and pries into ever, tuft of grass and every crevice

or hole in which insects or their larvm are likely to be found. When a flock visits the mead or waste, it

moves quickly from one part of the field to another; those foremost in the van finding abundance offooiUnd

leaving little behind them, the hinder birds are constantly rising, and pitching in front, until the whole field

has been examined; and the amount of good the, must do the farmer, the husbandman, and the country at