DRYOCOPUS MARTIUS.

Great Black Woodpecker.

Picus martins, Linn. Faun. Suec., p. 34.

—— niger, Briss. Om., tom. vi. p. 21.

Dryocopus martins, Boie, Isis, 1826, p. 977.

Dendrocopus pinetorum, Brehm, Vog. Deutschl., p. 185, tab. 13. fig. 3.

— martins, Brehm, ibid., p. 185.

Carbonarius martins, Kaup, Natiirl. Syst., p. 131.

Dryotomus martins, Swains. Faun. Bor.-Amer., p. 301.

Picus (Dryocopus) martins, Keys, et Bias. Wirbelth. Eur., p. 34.

Dryopicos martins, Malh. Mem. Acad. Nation. Metz, 1849, p. 320.

Dryopicus martins, Malh. Mon. Picid., tom. i. p. 31, tab. 10. figs. 5, 6, 7.

T he Great Black Woodpecker was first described as a British bird by Latham, in 1785, on the authority of

his friend Mr. Tunstall, who informed him that it had sometimes been seen in Devonshire. During the

interval between that date and 1869, no less than thirty notices of its occurrence in various English counties

have been recorded; and every ornithologist of repute, from Montagu to Yarrell, have included it as a

conspicuous species in our avifauna; besides which many other persons—collectors, sportsmen, and country

gentlemen—have stated to me, and, doubtless, to many others, that, in such and such a wood, on some

named day, they had seen a Great Black Woodpecker, one or more affirming that they had followed the

bird from tree to tree without being able, from its extreme shyness, to get withiu shooting distance. In the

‘ Field,’ of January 29, 1870, Mr. J . E. Harting gave a detailed account of the first twenty-five recorded

instances of the occurrence of the bird in our island; and in a note with which he has recently favoured

me, he has enumerated a number of others, making a total of thirty reported instances of this bird in Great

Britain. -$»It is not likely,” remarks Mr. Harting, “ that they can all be mistakes.”

I regret, however, that I am unable to endorse this opinion. I had hoped that so fine a Woodpecker

would have headed our indigenous Picidce; but, of the many persons who have asserted the occurrence of

the bird, not one, I believe, has been able to verify his statement by pointing out where an authenticated

British-killed specimen is to be seen; nor, I think, can any public museum or private collection produce one.

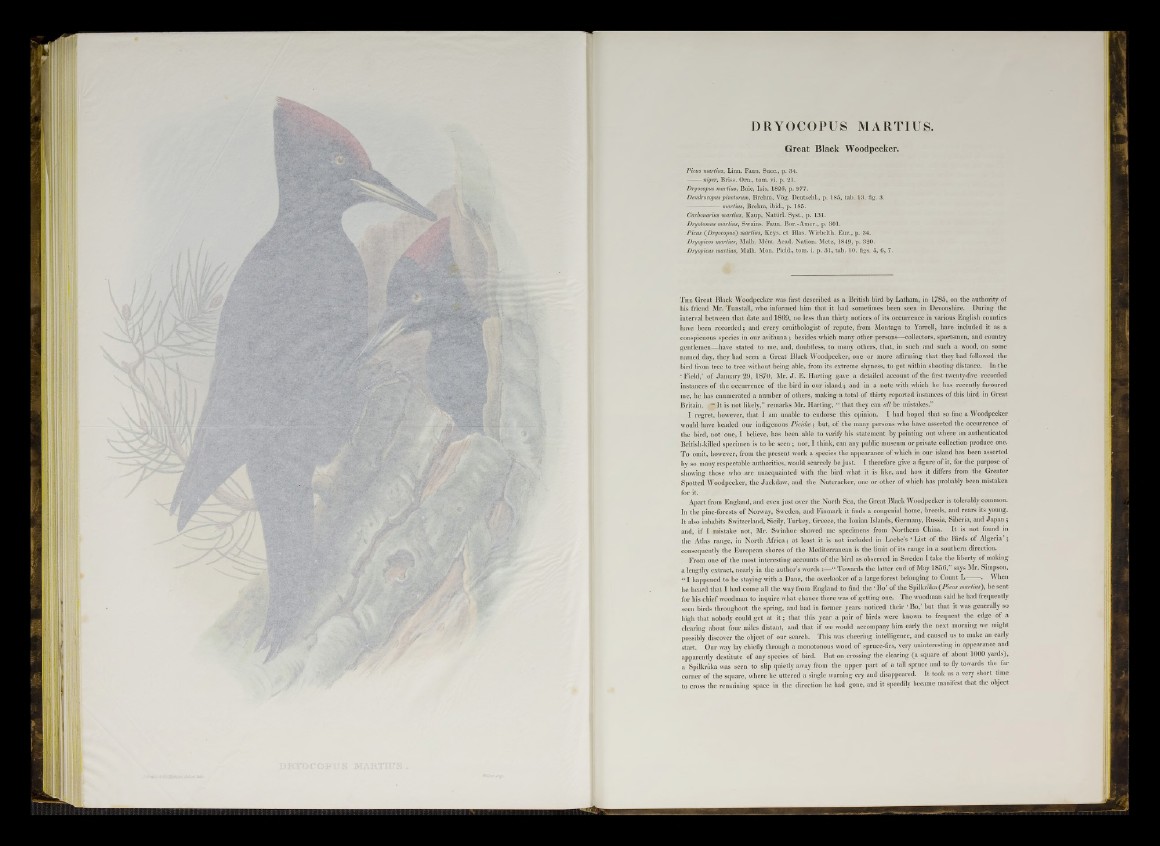

To omit, however, from the present work a species the appearance of which in our island has been asserted

by so many respectable authorities, would scarcely be just. I therefore give a figure of it, for the purpose of

showing those who are unacquainted with the bird what it is like, and how it differs from the Greater

Spotted Woodpecker, the Jackdaw, and the Nutcracker, one or other of which has probably been mistaken

for it.

Apart from England, and even just over the North Sea, the Great Black Woodpecker is tolerably common.

In the pine-forests of Norway, Sweden, and Finmark it finds a congenial home, breeds, and rears its young.

It also inhabits Switzerland, Sicily, Turkey, Greece, the Ionian Islands, Germany, Russia, Siberia, and Japan ;

and, if I mistake not, Mr. Swinlioe showed me specimens from Northern China. It is not found in

the Atlas range, in North Africa; at least it is not included in Loche’s ‘List of the Birds of Algeria’ ;

consequently the European shores of the Mediterranean is the limit of its range in a southern direction.

From one of the most interesting accounts of the bird as observed in Sweden I take the liberty of making

a lengthy extract, nearly in the author’s words :—“ Towards the latter end of May 1856,” says Mr. Simpson,

“ I happened to be staying with a Dane, the overlooker of a large forest belonging to Count L . When

he heard that I had come all the way from England to find th e ' Bo’ of the Spilkraka (\Ptcus martius), he sent

for his chief woodman to inquire what chance there was of getting one. The woodman said he had frequently

seen birds throughout the spring, and had in former years noticed their ‘ Bo,’ but that it was generally so

high that nobody could get at i t ; that this year a pair of birds were known to frequent the edge of a

clearing about four miles distant, and that if we would accompany him early the next morning we might

possibly discover the object of our search. This was cheering intelligence, and caused us to make an early

start. Our way lay chiefly through a monotonous wood of spruce-firs, very uninteresting in appearance and

apparently destitute of any species of bird. But on crossing the clearing (a square of about 1000 yards),

a Spilkraka was seen to slip quietly away from the upper part of a tall spruce and to fly towards the far

corner of the square, where he uttered a single warning cry and disappeared. It took us a very short time

to cross the remaining space in the direction he had gone, and it speedily became manifest that the object