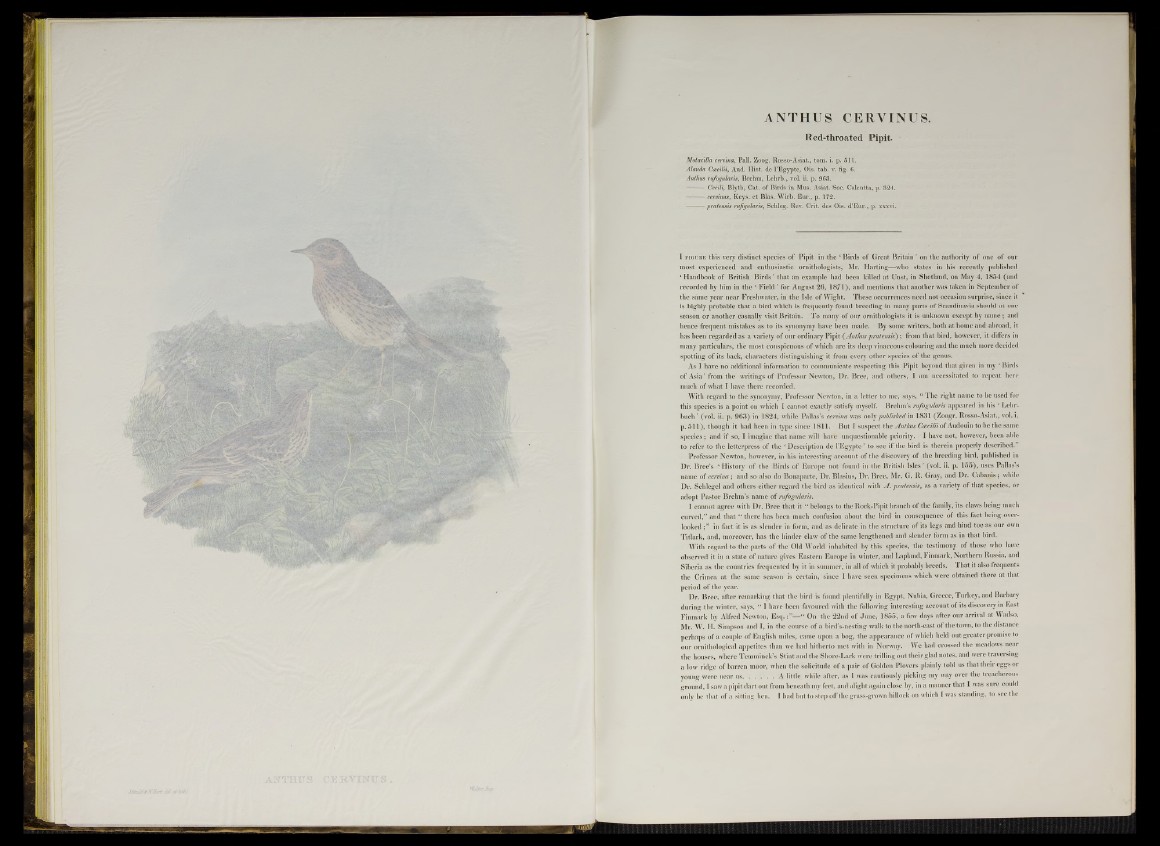

ANTHUS CERVINUS.

Red-throated Pipit.

Motacilla cervina, Pall. Zoog. Rosso-Asiat., tom. i. p. 511.

Alauda Cacilii, Aud. Hist, de l’Egypte, Ois. tab. v. fig. 6.

Anthus rufogtdaris, Brehm, Lehrb., vol. ii. p. 963.

— Cecili, Blyth, Cat. of Birds in Mus. Asiat. Soc. Calcutta, p. 324.

— cervinus, Keys, et Blas. Wirb. Em*., p. 172.

— pratensis rtifigularis, Schleg. Rev. Crit. des Ois. d’Eur., p. xxxvi.

I f ig u r e this very distinct species of Pipit in the ‘ Birds of Great Britain ’ on the authority of one of our

most experienced and enthusiastic ornithologists, Mr. Harting—who states in his recently published

‘ Handbook of British Birds | that an example had been killed at Uust, in Shetland, on May 4, 1854 (and

recorded by him in the ‘ Field ’ for August 26, 1871), and mentions that another was taken in September of

the same year near Freshwater, in the Isle of Wight. These occurrences need not occasion surprise, since it

is highly probable that a bird which is frequently found breeding in many parts of Scandinavia should at one

season or another casually visit Britain. To many of our ornithologists it is unknown except by name; and

hence frequent mistakes as to its synonymy have been made. By some writers, both at home and abroad, it

has been regarded as a variety of our ordinary Pipit (Anthus pratensis) ; from that bird, however, it differs in

many particulars, the most conspicuous of which are its deep vinaceous colouring and the much more decided

spotting of its back, characters distinguishing it from every other species of the genus.

As I have no additional information to communicate respecting this Pipit beyond that given in my ‘ Birds

of Asia* from the writings of Professor Newton, Dr. Bree, and others, I am necessitated to repeat here

much of what I have there recorded.

With regard to the synonymy, Professor Newton, in a letter to me, says, “ The right name to be used for

this species is a point on which I cannot exactly satisfy myself. Brehm’s rufogularis appeared in his 1 Lehr-

buch ’ (vol. ii. p. 963) in 1824, while Pallas’s cei'vina was only published in 1831 (Zoogr. Rosso-Asiat., vol. i.

p. 511), though it had been in type since 1811. But I suspect the Anthus ttmTwof Audouin to be the same

species; and if so, I imagine that name will have unquestionable priority. I have not, however, been able

to refer to the letterpress of the ‘ Description de l’Egypte ’ to see if the bird is therein properly described."

Professor Newton, however, in his interesting account of the discovery of the breeding bird, published in

Dr. Bree’s ‘ History of the Birds of Europe not found in the British Isles ’ (vol. ii. p. 155), uses Pallas’s

name of cervina; and so also do Bonaparte, Dr. Blasius, Dr. Bree, Mr. G. R. Gray, and Dr. Cabanis; while

Dr. Schlcgel and others either regard the bird as identical with A. pratensis, as a variety of that species, or

adopt Pastor Brehm’s name of rufogularis.

I cannot agree with Dr. Bree that it “ belongs to the Rock-Pipit branch of the family, its claws being much

curved,” and that “ there has been much confusion about the bird in consequence of this fact being overlooked

in fact it is as slender in form, and as delicate in the structure of its legs and hind toe as our own

Titlark, and, moreover, has the hinder claw of the same lengthened and slender form as in that bird.

With regard to the parts of the Old World inhabited by this species, the testimony of those who have

observed it it] a state of nature gives Eastern Europe in winter, and Lapland, Finmark, Northern Russia, and

Siberia as the countries frequented by it in summer, in all of which it probably breeds. That it also frequents

the Crimea at the same season is certain, since I have seen specimens which were obtained there at that

period of the year.

Dr. Bree, after remarking that the bird is found plentifully in Egypt, Nubia, Greece, Turkey, and Barbary

during the winter, says, “ I have been favoured with the following interesting account of its discovery in East

Finmark by Alfred Newton, E s q . “ On the 22nd of June, 1855, a few days after our arrival at Wadso,

Mr. W. H. Simpson and I, in the course of a bird’s-nesting walk to the north-east of the town, to the distance

perhaps of a couple of English miles, came upon a bog, the appearance of which held out greater promise to

our ornithological appetites than we had hitherto met with in Norway. We had crossed the meadows near

the houses, where Tcmminck’s Stint and the Shore-Lark were trilling out their glad notes, and were traversing

a low ridge of barren moor, when the solicitude of a pair of Golden Plovers plainly told us that their eggs or

young were near us. . . . . . A little while after, as I was cautiously picking my way over the treacherous

ground, I saw a pipit dart out from beneath my feet, and alight again close by, in a manner that I was sure could

only be that of a sitting hen. I had but to step off the grass-grown hillock on which I was standing, to see the