“ I must here mention that the rather high and ragged hills which hem in the sides of the Gulf of Smyrna

and the Valley and Gulf of Boumatut, particularly towards the north, and form the foot of the higher hills,

consist of surface heds of limestone, covered with large erratic blocks of granite, of different shapes and

sizes. These massive stones, heaped one above another, leave no place for vegetation of any sort, except

the Asp/iodelas ramosus. Our way led northwards towards these ' pathless mountains; and, after a

wearisome ascent up the empty bed of a torrent, oft whose hanks the beautiful Nerium oleatukr and the

charming Agnus cm/us grew luxuriantly, we arrived at the foot of the higher range ahove mentioned. We

had hardly begun to mount the hill before we noticed that there was not a stone or block which was not

covered with the white excrement of these birds, they resorted there in such multitudes ; bat how great was

our astonishment when we saw, at a distance of about 20 0 metres above us, the rocks covered with white,

as if lime had been spread out for 200 square yards ! On arriving there, we found a real camp and battlefield

in one ; the nests were in thousands, some qnite open and uncovered, others so concealed amongst

the blocks of stone, that it was necessary to turn these over to find them ; some were more than a foot

below the surface, and others could not he reached with the arms. They were often so close as to touch one

another, and were made with but little care, the birds contenting themselves with a slight hollow in the

ground, in which are placed some dead stalks of the Agnus castas, and, in a few instances, a lining of grass ;

in many cases the eggs were lying on the bare earth. This mode of nesting exposed them to the many

enemies which were roaming about on all sides ; it was for this reason that I remarked that we had found

a battle-field as well as an encampment ; for, to give you an idea of the number of nestlings destroyed by

jackals, martens, wild cats, rats, &c., I may state that in a space of about five square yards I counted

fourteen pairs of wings and the remains of three old birds; and who can tell the number of eggs destroyed

by snakes ? Indeed, it is Wonderful how the Rose-Starlings can propagate at all with so many enemies to

encounter.

“ Thé e«*gé, of which we found very few, measure, oil the average, 13 lines in length by 9^ lines in breadth.

I say, on the average, because we did not find two exactly alike, some being pear-shaped, others elliptical ;

some are fleshy white, others pearl-white tinged with blue, and some have a few dark specks at the larger

end. The shell is very beautiful, strong, and shining.

“ The perseverance with which the Rose-Starlings search for grasshoppers seems to be due, not so much

for a supply of food, as for an instinctive desire of destruction or antipathy against them. One morning, as

I was observing five Rose-Starlings eating the fruit of a white mulberry-tree with great avidity, I saw two

or three of them dart down suddenly from the tree to the ground in order to kill some grasshoppers which

appeared between the swathes of a mown field of grass, and leave them without eating any of them. The

birds are so far from shy, that a person can easily remain within four or five paces without frightening

them, and on the trees they will remain with still greater confidence.”

“ This well-known species,” states Mr. Jerdon, “ makes its appearance in the peninsula of India about the

end of November or beginning of December, associating in vast flocks, and commits great havoc on the

grain-fields, especially in those of the Cholum or Jowaree (Andropogon Sorghum). When the grain is cut, it

commonly feeds on insects, which it seeks for on the ground ; also on various grass-seeds, fruit, and flower-

buds. It disappears in March, though straggling parties are met with even in April. The majority of the

birds in a flock are in an immature plumage, of dirty fawn-colour, in lieu of the delicate salmon-tint of the

adult.” Mr. Elliot has the following interesting note on this species It is very voracious arid injurious

to the crops of the White Jowaree, in the fields of which the farmer is obliged to station numerous

watchers, who, with slings and a long rope or thong (which they crack dexterously, making a loud report),

endeavour to drive the depredators away. The moment the sun appears above the horizon, they are on the

wing, and, at the same instant, shouts, cries, and the cracking of long whips resound from every side. The

birds, however, are so active that, if they are able to alight on the stalks for an instant, they can pick out

several grains. About 9 or 10 o’clock a.m ., the exertions of the watchmen cease, and the birds do not

renew their plundering till the evening. After sunset they are seen in flocks of many thousands, retiring to

the trees and jungles for the night. They prefer the half-ripe Jowaree, whilst the farinaceous matter is still

soft and milky.”

We learn from Bechstein that, like the Starling, the bird possesses considerable imitative powers, and that

a connoisseur in the song of birds, who heard the notes of one in captivity, without seeing the bird, fancied

he was listening to two Starlings, two Goldfinches, and perhaps a Siskin, and, when he found that the sounds

all emanated from'a single bird, could not conceive how so much music could proceed from the same throat.

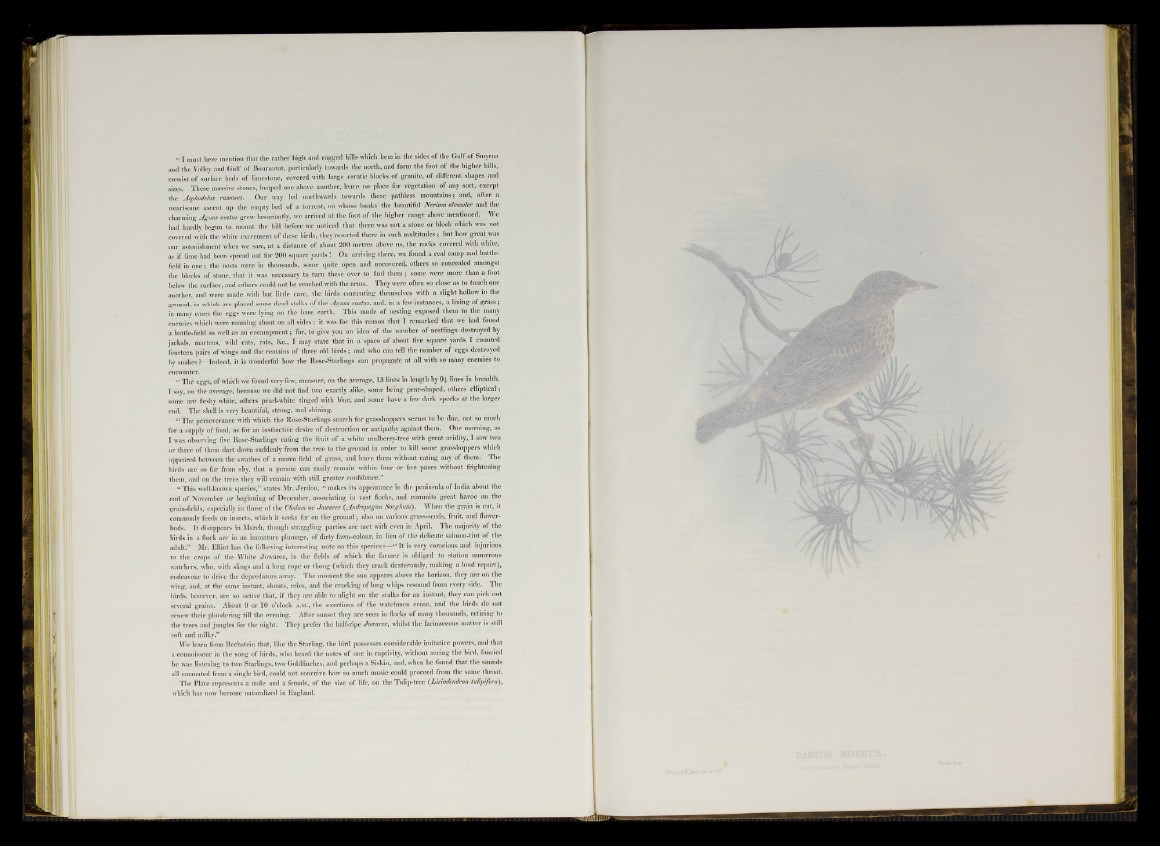

The Plate represents a male and a female, of the size of life, on the Tulip-trce (IAriodendron tulipifera),

which has now become naturalized in England.