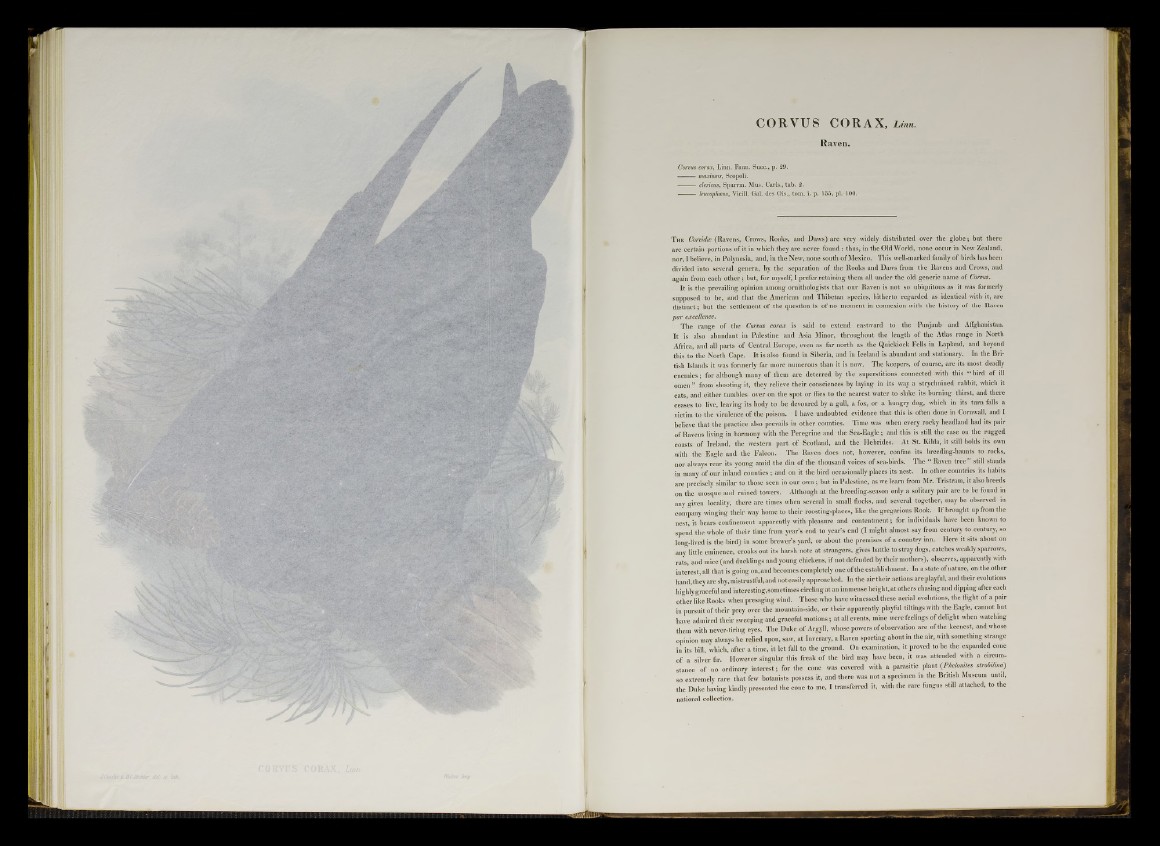

Raven.

Corvus corax, Linn. Faun. Suec., p. 29.

maximus, Scopoli.

clericus, Sparrm. Mus. Carls., tab. 2.

leucophtsus, Vieill. Gal. des Ois., tom. i. p. 155, pi.-100.

T he Corvidte (Ravens, Crows, Rooks, and Daws) are very widely distributed over the globe; but there

are certain portions of it in which they are never found: thus, in the Old World, none occur in New Zealand,

nor, I believe, in Polynesia, and, in the New, none south of Mexico. This well-marked family of birds has been

divided into several genera, by the separation of the Rooks and Daws from the Ravens and Crows, and

again from each other; but, for myself, 1 prefer retaining them all under the old generic name of Corvus.

It is the prevailing opinion among ornithologists that our Raven is not so ubiquitous as it was formerly

supposed to be, and that the American and Thibetan species, hitherto regarded as identical with it, are

distinct; but the settlement of the question is of no moment in connexion with the history of the Raven

par excellence.

The range of the Corvus corax is said to extend eastward to the Punjaub and Affghanistan.

It is also abundant iu Palestine and Asia Minor, throughout the length of the Atlas range in North

Africa, and all parts of Central Europe, even as far north as the Quickiock Fells in Lapland, and beyond

this to the North Cape. It is also found in Siberia, and in Iceland is abundant and stationary. In the British

Islands it was formerly far more numerous than it is now. The keepers, of course, are its most deadly

enemies; for although many of them are deterred by the superstitions connected with this “ bird of ill

omen ” from shooting it, they relieve their consciences by laying in its way a strychnined rabbit, wbicli it

eats, and either tumbles over on the spot or flies to the nearest water to slake its burning thirst, and there

ceases to live, leaving its body to be devoured by a gull, a fox, or a hungry dog, which in its turn falls a

victim to the virulence of the poison. I have undoubted evidence that this is often done in Cornwall, and I

believe that the practice also prevails in other counties. Time was when every rocky headland had its pair

of Ravens living in harmony with the Peregrine and the Sea-Eagle; and this is still the case on the rugged

coasts of Ireland, the western part of Scotland, and the Hebrides. At St. Kilda, it still bolds its own

with the Eagle and the Falcon. The Raven does not, however, confine its breeding-haunts to rocks,

nor always rear its young amid the din of the thousand voices of sea-birds. The “ Raven tree ” still stands

in many of our inland counties ; and on it the bird occasionally places its nest. In other countries its habits

are precisely similar to those seen in our own; but in Palestine, as we learn from Mr. Tristram, it also breeds

on the mosque and ruined towers. Although at the breeding-season only a solitary pair are to be found in

any given locality, there are times when several in small flocks, and several together, may be observed in

company winging their way home to their roosting-places, like the gregarious Rook. If brought up from the

nest, it bears confinement apparently with pleasure and contentment; for individuals have been known to

spend the whole of their time from year’s end to year’s end (I might almost say from century to century, so

long-lived is the bird) in some brewer’s yard, or about the premises of a couutry inn. Here it sits about on

any little eminence, croaks out its harsh note at strangers, gives battle to stray dogs, catches weakly sparrows,

rats, and mice (and ducklings and young chickens, if not defended by their mothers), observes, apparently with

interest, all that is going on, and becomes completely one of the establishment. In a state of nature, on the other

hand, they are shy, mistrustful, and not easily approached. In the air their actions are playful, and their evolutions

highly graceful and interesting, sometimes circling at an immense height, at others chasing and dipping after each

other like Rooks when presaging wind. Those who have witnessed these aerial evolutions, the flight of a pair

in pursuit of their prey over the mountain-side, or their apparently playful tiltings with the Eagle, cannot but

have admired their sweeping and graceful motions; at all events, mine were feelings of delight when watching

them with never-tiring eyes. The Duke of Argyll, whose powers of observation are of the keenest, and whose

opinion may always be relied upon, saw, at Inverary, a Raven sporting about in the air, with something strange

iu its bill, which, after a time, it let fall to the ground. On examination, it proved to be the expanded cone

of a silver fir. However singular this freak of the bird may have been, it was attended with a circumstance

of no ordinary interest; for the cone was covered with a parasitic plant (Phelomtes strobthna)

so extremely rare that few botanists possess it, and there was not a specimen in the British Museum until,

the Duke having kindly presented the cone to me, I transferred it, with the rare fungus still attached, to the

national collection.