Picus major, Linn. Syst. Nat., tom. i. p. 176.

ctssa, Pall. Zoog. Ross. Asiat., tom. i. p. 442.

pipra, Macgill. Hist. Brit. Birds, vol. in. p. 30.

• varius major, Briss. Orn., tom. iv. p. 34.

— — discolor, Frisch, Vog., pi. 36.

Dryobates major, Boie, Isis, 1826.

Dendrocopus major, Koch, Baier. Zool.

Picus Baskhiriensis, Verr., 1854.

brevirostris, P. alpestris et P. mesopilus, Reichenb. Handb. Spec. Orn., p. 365, pi. dcxxxiii. fig. 4212.

pilyopicus, P. montanus, P. pinetorum, P. frondium, P. leucorum et P. sordidus, Brehm.

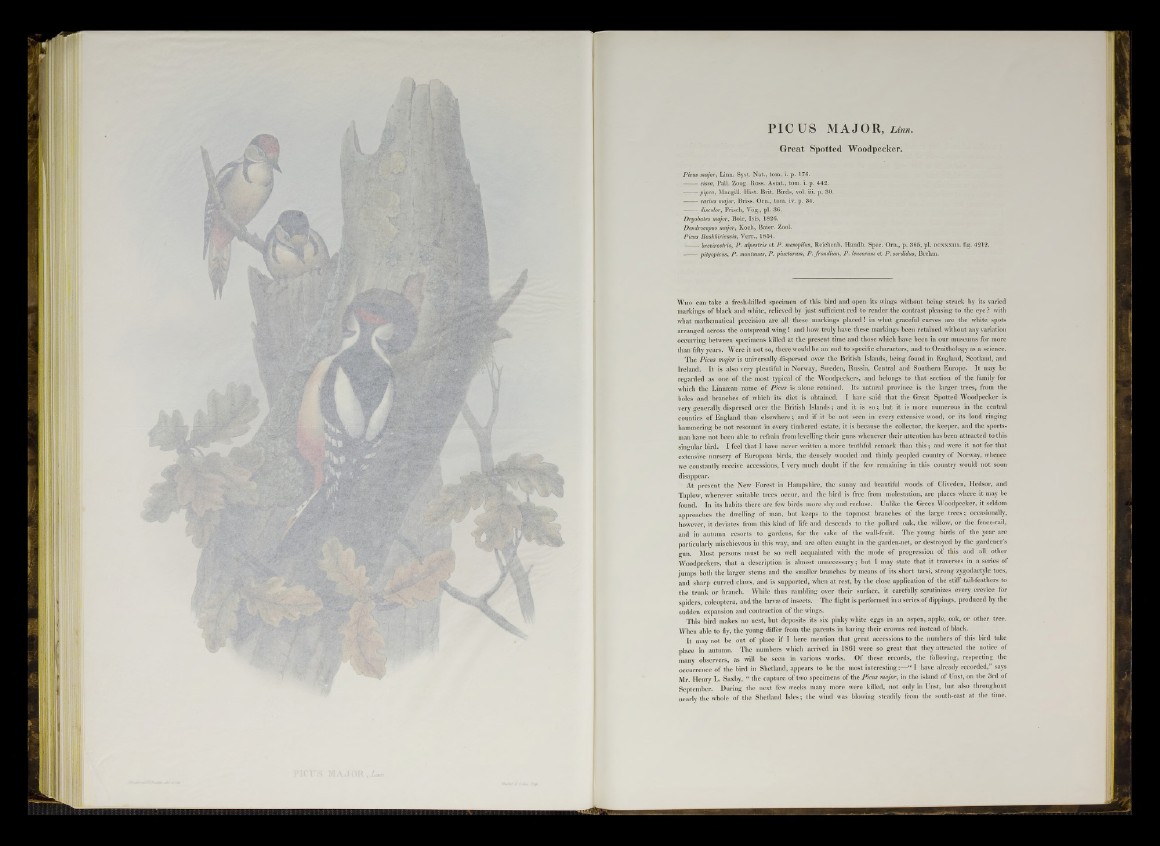

W ho can take a fresh-killed specimen o f this bird and open its wings without being struck by its varied

markings of black and white, relieved by just sufficient red to render the contrast pleasing to the eye ? with

what mathematical precision are all these markings placed! in what graceful curves are the white spots

arranged across the outspread wing! and how truly have these markings been retained without any variation

occurring between specimens killed at the present time and those which have been in our museums for more

than fifty years. Were it not so, there would be an end to specific characters, and to Ornithology as a science.

The Picus major is universally dispersed over the British Islands, being found in England, Scotland, and

Ireland. It is also very plentiful in Norway, Sweden, Russia, Central and Southern Europe. It may be

regarded as one of the most typical of the Woodpeckers, and belongs to that section of the family for

which the Linniean name of Picus is alone retained. Its natural province is the larger trees, from the

boles and branches of which its diet is obtained. I have said that the Great Spotted Woodpecker is

very generally dispersed over the British Islands; and it is so ; but it is more numerous in the central

counties of England than elsewhere; and if it be not seén in every extensive wood, or its loud ringing

hammering be not resonant in every timbered estate, it is because the collector, the keeper, and the sportsman

have not been able to refrain from levelling their guns whenever their attention has been attracted to this

singular bird. I feel that I have never written a more truthful remark than this; and were it not for that

extensive nursery of European birds, the densely wooded and thinly peopled country of Norway, whence

we constantly receive accessions, I very much doubt if the few remaining in this country would not soon

disappear.

At present the New Forest in Hampshire, the sunny and beautiful woods of Cliveden, Hedsor, and

Taplow, wherever suitable trees occur, and the bird is free from molestation, are places where it may be

found. In its habits there are few birds more shy and recluse. Unlike the Green Woodpecker, it seldom

approaches the dwelling of man, but keeps to the topmost branches of the large trees; occasionally,

however, it deviates from this kind of life and descends to the pollard oak, the willow, or the fence-rail,

and in autumn resorts to gardens, for the sake of the wall-fruit. The young birds of the year are

particularly mischievous in this way, and are often caught in the garden-net, or destroyed by the gardener’s

gun. Most persons must be so well acquainted with the mode of progression of this and all other

Woodpeckers, that a description is almost unnecessary; but I may state that it traverses in a series of

jumps both the larger stems and the smaller branches by means of its short tarsi, strong zygodactyle toes,

and sharp curved claws, and is supported, when at rest, by the close application of the stiff tail-feathers to

the trunk or branch. While thus rambling over their surface, it carefully scrutinizes every crevice for

spiders, coleóptera, and the larvae of insects. The flight is performed in a series of dippings, produced by the

sudden expansion aud contraction of the wings.

This bird makes no nest, but deposits its six pinky white eggs in an aspen, apple, oak, or other tree.

When able to fly, the young differ from the parents in having their crowns red instead of black.

It may not be out of place if I here mention that great accessions to the numbers of this bird take

place in autumn. The numbers which arrived in 1861 were so great that they attracted the notice of

many observers, as will be seen in various works. Of these records, the following, respecting the

occurrence of the bird in Shetland, appears to be the most interesting:—“ I have already recorded,” says

Mr. Henry L. Saxby, “ the capture of two specimens of the Picus major, in the island of Unst, on the 3rd of

September. During the next few weeks many more were killed, not only in Unst, but also throughout

nearly the whole of the Shetland Isles; the wind was blowing steadily from the south-east at the timé.