YUNX TORQUILLA.

Wryneck.

Yunx torquilla Linnrei et auctorum.

W ryneck, Cuckoo’s mate, Snake-bird! How shall I commence its history ? For its every action and whole

economy are as singular as the markings of its plumage are chaste and beautiful. Mate of the Cuckoo it

has been called, because it arrives in the spring, foretelling, like that hird, that summer is near at hand.

Its peculiar cry is known to every cottager, and welcome is its monotonous and repeated call of pee, pee, pee.

Africa, which it has lately left, is its winter residence; but as the snn advances towards the north, it follows

in his path, well knowingthat it will find a congenial home in Great Britain. What, if I depict it in one of

its grotesque attitudes, when it writhes its head, snake-like, from side to side, with its neck contracted to the size

of a quill; or in the period of courtship, when, with erected crest, drooping wings, and outspread tail, it is

bowing and coquetting before the object of its attention ? If I had portrayed it thns, it would scarcely have

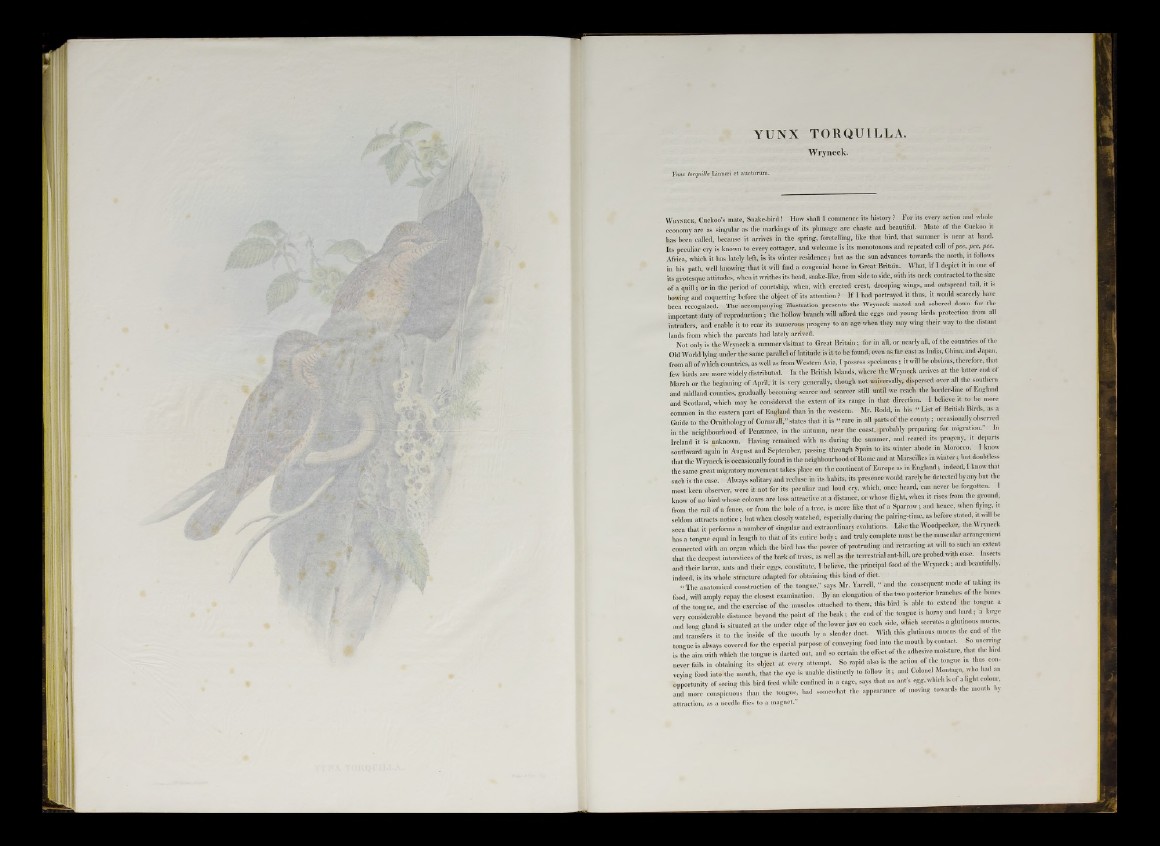

been recognized. The accompanying illustration presents the Wryneck mated and sobered down for the

importantduty of reproduction; the hollow branch will afford the eggs and young birds protection from all

intruders, and enable it to rear its numerous progeny to an age when they may wing their way to the distant

lands from which the parents had lately arrived. .......................... r - ■^ ~ :

Not only is the Wryneck a summer visitant to Great Britain; for in all, or nearly all, of the countries.of the

Old World lying under tile same parallel of latitude is it to be found, even as far east as India, China, and Japan,

from all of which countries, as well as from Western Asia, I possess specimens; it will be obvious, therefore, that

few birds are more widely distributed. In the British Islands, where the Wryneck arrives at the latter end of

March or the beginning of April, it is very generally, though not universally, dispersed over all the southern

and midland counties, gradually becoming scarce and scarcer still until we reach the border-line of England

and Scotland, which may he considered the extent of its range in that direction. I believe it to be more

common in the eastern part of England than in the western. Mr. Rodd, in his “ List of British Birds, as a

Guide to the Ornithology of Cornwall,” states that it is “ rare in all parts of the county; occasionally observed

in the neighbourhood of Penzance, in the antumn, near the coast, .probably preparing for migration.” In

Ireland it is unknown. Having remained with us- during the summer, and reared its progeny, it departs

southward again in Angust and September, passing through Spain to its winter abode in Morocco. I know

that the Wryneck is occasionally found in the néighbourhood of Rome and at Marseilles in winter; bnt doubtless

the same great migratory movement takes place on the continent of Europe as in England; indeed, I know that

such is the case. Always solitary and recluse in its habits, its presence would rarely be detected by any but the

most keen observer, were it not for its peculiar and loud cry, which, once heard, can never be forgotten. I

know of no bird whose colours are less attractive at a distance, or whose fiight, when it rises from the ground,

from the rail of a fence, or from the bole of a tree, is more like that of a Sparrow; and hence, when fiying, it

seldom attracts notice; bnt when closely watched, especially during the pairing-time, as before stated, it mil be

seen that it performs a number of singular and extraordinary evolutions. Like the Woodpecker, the Wryneck

has a tongue equal in length to that of its entire body; and truly complete must be the muscular arrangement

connected with an organ which the bird has the power of protruding and retracting at mil to such an extent

that the deepest interstices of the bark of trees, as well as the terrestrial ant-hill, are probed with ease. Insects

and their larvm, ants and their eggs, constitute, I believe, the principal food of the Wryneck; and beautifully,

indeed, is its whole structure adapted for obtaining this kind of ffiet.

“ The anatomical constrnction of the tongue,” says Mr. Yarrell, | and the consequent mode of takingits

food, will amply repay the closest examination. By an elongation of the two posterior branches of the hones

of the tongue, and the exercise of the muscles attached tó them, this bird is able to extend the tongue a

very considerable distance beyond the point of the beak; the end of the tongue is horny and hard; a large

and long gland is situated at the under edge of the lower jaw on each side, which secretes a glutinous mucus,

and transfers it to the inside of the mouth by a slender duct. With this glutinous mucus the end of the

tongue is always covered for the especial purpose of conveying food into the mouth by contact. So unerring

is the aim with which the tongue is darted out, and so certain the effect of the adhesive moisture, that the bird

never fails in obtaining its object at every attempt. So rapid also is the action of the tongue in thus conveying

food into the mouth, that the eye is unable distinctly to follow i t ; and Colonel Montagu who had an

opportunity of seeing this bird feed while confined in a cage, says that an ant's egg, which is of a light colour,

and more conspicuous than the tongue, had somewhat the appearance of moving towards the mout y

attraction, as a needle flies to a magnet.”