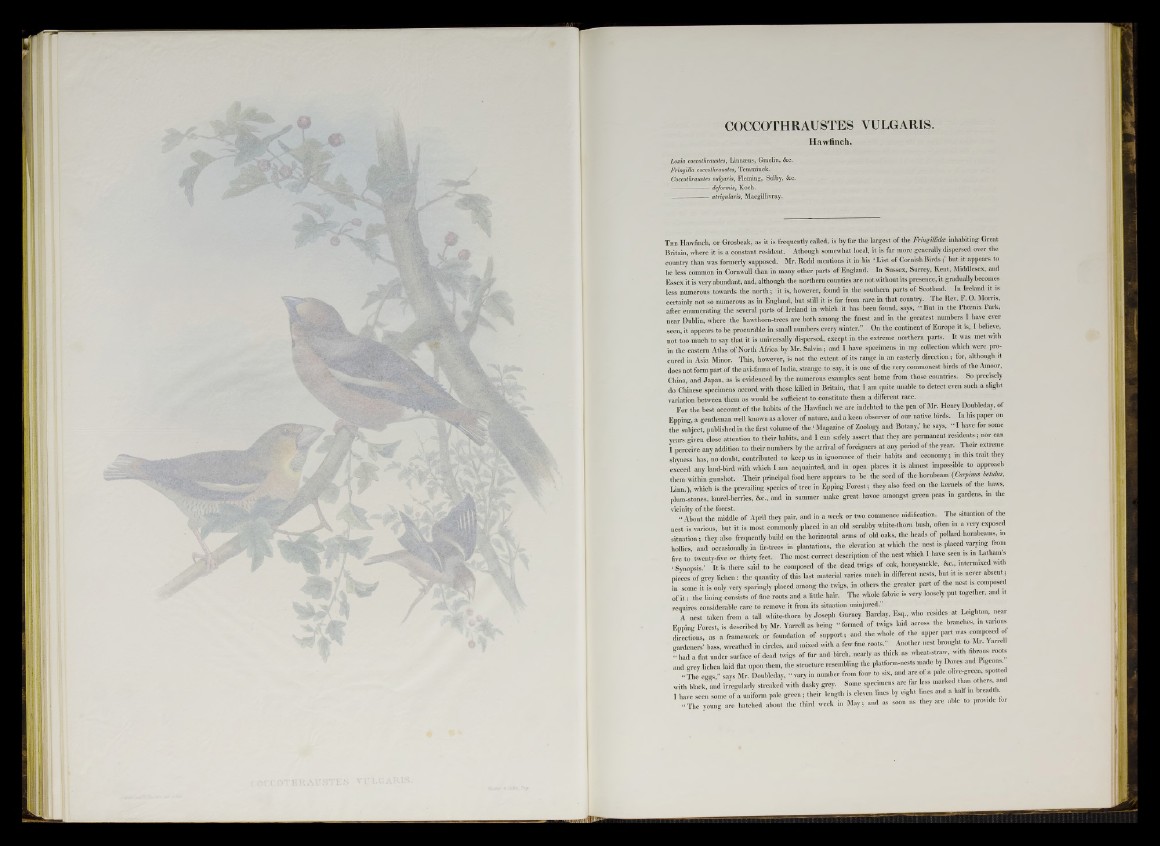

Hawfinch.

Loxia coccothraustes, Linnaeus, Gmelin, &c.

Fringilla coccothraustes, Temminck.

Coccothraustes vulgaris, Fleming, Selby, &c.

deformis, Koch.

— atrigularis, Macgillivray.

T h e Hawfinch, or Grosbeak, as it is frequently called, is by far the largest of the Frmgillidai inhabiting Great

Britain, where it is a constant resident. Athough somewhat local, it is far more generally dispersed over the

country than was formerly supposed. Mr. Rodd mentions it in his ‘ List of Cornish B ir d s b u t it appears to

be less common in Cornwall than in many other parts of England. In Sussex, Surrey, Kent, Middlesex, and

Essex it is very abundant, and, although the northern counties are not without its presence, it gradually becomes

less numerous towards the north; it is, however, found in the southern parts of Scotland. In Ireland it is

certainly not so numerous as in England, but still it is far from rare in that country. The Rev. F. O. Morris,

after enumerating the several parts of Ireland in which it has been found, says, “ But in the Fhcenix Park,

near Dublin, where the hawthom-trees are both among the finest and in the greatest numbers I have ever

seen, it appears to be procurable in small numbers every winter.” On the continent of Europe it is, I believe,

not too much to say that it is universally dispersed, except in the extreme northern parts. It was met with

in the eastern Atlas of North Africa by Mr. Salvin; and I have specimens in my collection which were procured

in Asia Minor. This, however, is not the extent of its range in an easterly direction; for, although it

does not form part of the avi-fanna of India, strange to say, it is one of the very commonest birds of the Amoor,

China, and Japan, as is evidenced by the numerous examples sent home from those conntries. So precisely

do Chinese specimens accord with those killed in Britain, that I am quite unable to detect even such a slight

variation between them as would be sufficient to constitute them a different race.

For the best account of the habits of the Hawfinch we are indebted to the pen of Mr. Henry Doubleday, of

Epping, a gentleman well known as a lover of nature, and a keen observer of our native birds. In his paper on

the subject, published in the first volume of the ■ Magazine of Zoology and Botany,’ he says, “ I have for some

years given close attention to their habits, and I can safely assert that they are permanent residents; nor can

I perceive any addition to their numbers by the arrival of foreigners at any period of the year. Their extreme

shyness has, no doubt, contributed to keep us in ignorance of their habits and economy; in this trait they

exceed any land-hird with which I am acquainted, and in open places it is almost impossible to approach

them within gunshot. Their principal food here appears to be the seed of the hornbeam (Carpims hetulm,

Linn.), which is the prevailing species of tree in Epping Forest; they also feed on the kernels of the haws,

plum-stones, laurel-berries, &c„ and in summer make great havoc amongst green peas in gardens, m the

vicinity of the forest. ^

i About the middle of April they pair, and in a week or two commence notification. The situation of the

nest is various, but it is most commonly placed in an old scrubby white-thorn bush, often in a very exposed

situation; they also frequently build on the horizontal arms of old oaks, the heads of pollard hornbeams, in

hollies, and occasionally in fir-trees in plantations, the elevation at which the nest is placed varying from

five to twenty-five or thirty feet. The most correct description of the nest which I have seen is in Latham s

S Synopsis.’ It is there said to be composed of the dead twigs of oak, honeysuckle, &c., intermixed with

pieces of grey lichen: the quantity of this last material varies much in different nests, but it is never absent;

in some it is only very sparingly placed among the twigs, in others the greater part of the nest ,s composed

of i t : the lining consists of fine roots and a little hair. The whole fabric is very loosely put together, and it

requires considerable care to remove it from its situation uninjured.’’

A nest taken from a tall white-thom by Joseph Gurney Barclay, Esq., who resides at Leighton, near

Epping Forest, is described by Mr. Yarrell as being j formed of twigs laid across the branches, in various

directions, as a framework or foundation of support; and the whole of the upper part was “ mposed o

gardeners' bass, wreathed in circles, and mixed with a few fine roots.” Another nest brought to Mr. Yarrell

■■ had a flat under surface of dead twigs of fur and birch, nearly as thick as wheat-straw, with fibrous roots

and grey lichen laid flat upon them, the structure resembling the platform-nests made by Doves and Pigeons.

.. The eggs ” says Mr. Doubleday, g vary in number from four to six, and are of a pale ohve-green spotted

with black, and irregularly streaked with dusky grey. Some specimens are far less

I have seen some of a uniform pale green; their length is eleven lines by eight lmes and a half in breadth

■•The young are hatched about the third week in May; and as soon as they are able to provide for