large is, in my estimation, immense, feeding, as they, almost exclusively do, on 'vireworms, larvte of all

kinds, grasshoppers, worms, flies, and insects generally.

It may fairly be asked if the vast hordes of this bird seen in autumn and winter are all natives of our

islands, or are partly composed of accessions from the Continent. I have no hesitation in saying that the

latter is the case, and that these winter visitants migrate again in spring to the countries they left; in autumn ;

the circumstance of numbers being killed by flying against the lighthouses on our coast tends to confirm

such an opinion. When the Starlings are frozen out in the northern parts of the British Islands, as is

frequently the case, they seek the warmer portions of Devon and Cornwall, and usually find shelter there;

but should those counties also be visited by rigorous weather, they die by hundreds. During my visit to

Tregothnan, during the very severe month of January 1867, the Starlings perished in great numbers; and

every Missel Thrush and many of the Redwings and Fieldfares also fell victims to the rigours of the season.

It was no unusual sight to see Starlings lying dead in lens or even twenties round the farmsteads, and

in still greater numbers in the belfries of the churches in which they had sought shelter. It is not a little

singular that, although the Starling is so abundant in Cornwall during the winter months, few, if any, stay to

breed in that county.

From and after the autumnal migration, and all through the winter months,’’ says Mr. Rodd, “ until the

return movement in the spring we are visited in the west of England by vast flights of Starlings, which

disperse in flocks of varying numbers over the open fields during the day, wheeling to and fro, from field to

field, and occupying themselves in feeding until the approach of twilight, when they all unite in various sized

companies, and repair to their roosting-ground, which, in the absence of plantations, is in osier-beds, rnshy

bottoms, amidst flogs, sedges, &c. Where, however, as in this locality, at Trengivainton and Trevethoe, a

few plantations of young firs, evergreens, &c. are sparingly dispersed, it is a sight of no ordinary interest to

see the almost uninterrupted stream of these birds pouring in from sunset to dusk, forming at last a

countless mass which literally fills the plantation. When the day breaks, the birds disperse in small flocks

in, various directions until they again reunite in the evening. Previous to this grand assembly settling down

to roost, they take wheeling flights round and round their haunts, sometimes presenting the appearance of a

huge black cloud.”

With reference to the immense flocks assembling in the evening, Bishop Stanley s a y s “ At first they

might be seen advancing high in the air like a dark cloud, which in an instant, as if by magic, became

almost invisible—the whole body, by some mysterious watchword or signal, changing their course and

presenting their wings to view edgeways instead of exposing, as before, their full expanded spread. Again,

in another moment, the cloud might be seen descending in a graceful sweep, so as almost to brush the earth

as they glanced along; then once more they were seen spiring in wide circles on high, till at length, with

one simultaneous rush, down they glided with a roaring noise of wing till the vast mass buried itself unseen,

but not unheard, amidst a bed of reeds; for no sooner were they perched than every throat seemed to open

itself, forming one incessant confusion of tongues.”

“ Any traveller from Norwich on the Yarmouth line,” says Mr. Stevenson, “ on looking towards the

river, near Brundall station, between seven and eight o’clock on a summer evening may see the Starlings

making for Sarlingham broad; where in some places so great are the numbers that nightly assemble

that the reeds are literally trampled down with their weight. To those at all interested in the habits of

birds, I know few sights more likely to excite wonder and admiration than the regular arrival of the Starlings

from all quarters to any particular broad. Mr. J . G. Davey tells me, ‘ One night I watched a single

flock, which appeared to extend over about five acres, as they were wheeling round, when another mass came

from the south-west; I can form no estimate of the number; the former flock I considered large till these

came; they also circled round and joined the others. They settled down in the wood in two parties, and

occupied about thirty acres.1 ”—Birds o f Norfolk, vol. i. pp. 249, 250, 251.

Nuneham Park, near Oxford, is one of the roosting-places of the Starling. The birds have taken up a

position in the fine Pinetum therein, adding nothing to the beauty or to the sweetness of that charming spot;

nevertheless the very estimable owner, the Rev. William Vernon-Harcourt, permits them to remain in peace.

Probably the congregation which there assemble is formed by all the Starlings of that portion of the valley

of the Thames and its tributaries.

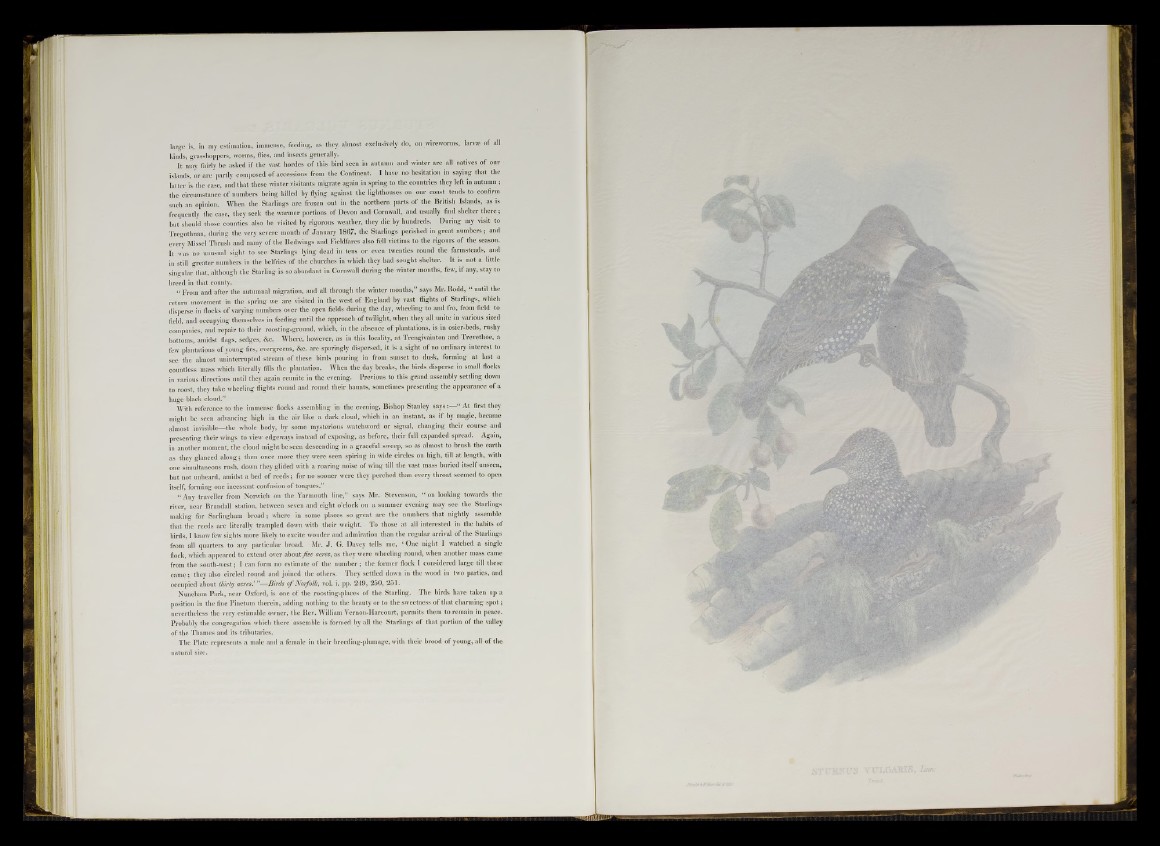

The Plate represents a male and a female in their breeding-plumage, with their brood of young, all of the

natural size.