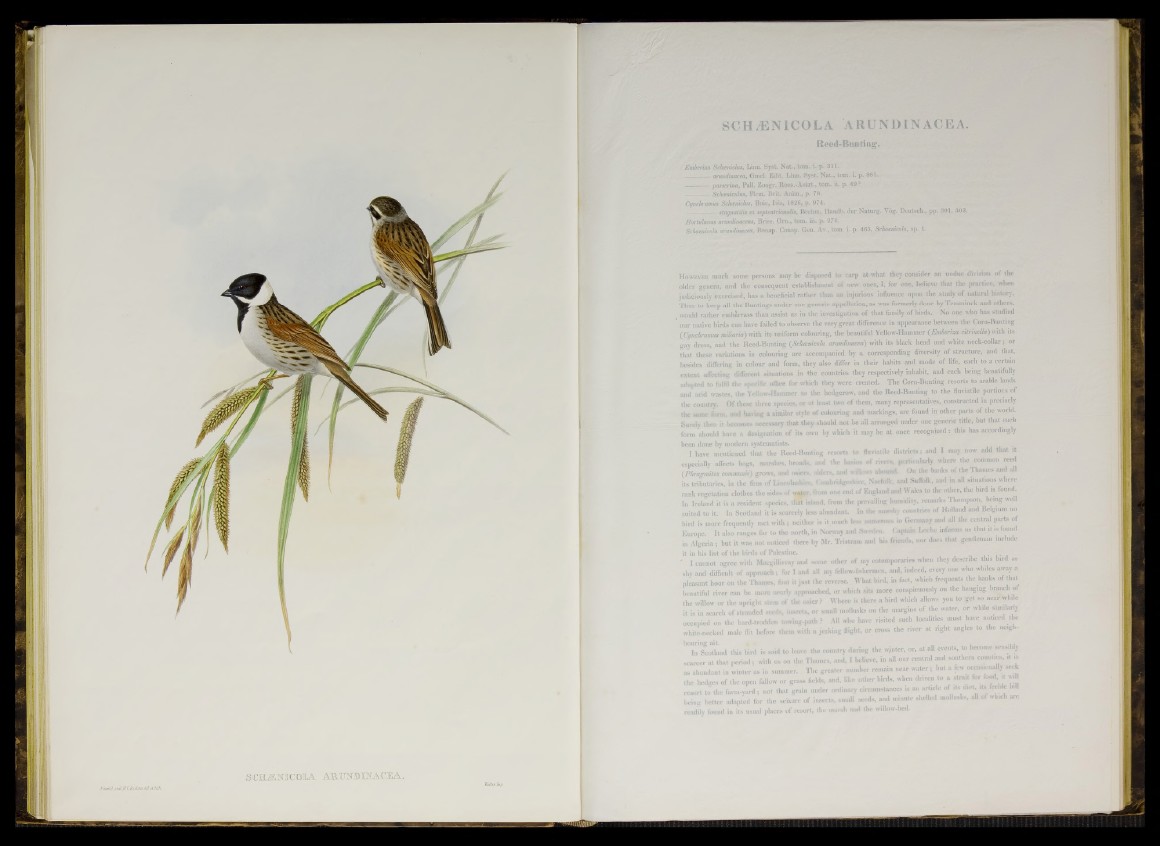

SCHJEMCOIA AB.UIiDIEA.CEA.

Reed-Bunting.

Emberiza Schaniclus., Linn. Syst. Nat., tom. i. p. 311.

----------- arundinacea, Gmel. Edit. Linn. Syst. Nat., tom. i. p. 881. -

----------- passerina, Pall. Zoogr. Ross.-Asiat., tom. ii. p. 49 ?

— Schcenicultts, Rem. Brit Anim., p. 78.

Cynchramus ScJueniclus, Boie, Isis, 1826, p. 974.

________- stagnatilis et septentrionalis, Brehm, Handb. der Naturg. Vog. Deutsch., pp. 301, 302.

Hortulanus arundinaceus, Briss. Orn., tom. iii. p. 274.

Schaenicola arundinacea, Bonap. Consp. Gen. A v., tom. i. p. 463, Schaenicola, sp. 1.

H ow ev e r much some persons may be disposed to carp at what they consider an undue division of the

older genera, and the consequent establishment of new ones, I, for one, believe that the practice, when

judiciously exercised, has a beneficial rather than an injurious influence upon the .study of natural history.

Thus to keep all the Buntings under one generic appellation, as was formerly done by Temminck and others,

, would rather embarrass than assist us iu the investigation of that family of birds. No one who has studied

our native birds can have failed to observe the very great difference in appearance between the Corn-Bunting

(Cynchramxts miliaria) with its uniform colouring, the beautiful Yellow-Hammer (Emberiza citnnella) with its

gay dress, and the Reed-Bunting {Schaenicola arundinacea) with its black head and white neck-collar; or

that these variations in colouring are accompanied by a corresponding diversity of structure, and that,

besides differing iu colour and form, they also differ in their habits and mode of life, each to a certain

extent affecting different situations in the countries they respectively inhabit, and each being beautifully

adapted to fulfil the specific office for which they were created. The Corn-Bunting resorts to arable lands

and arid wastes, the Yellow-Hammer to the hedgerow, and the Reed-Bunting to the fluviatile portions of

the country. Of these three species, or at least two of them, many representatives, constructed in precisely

the same form, and having a similar style of colouring and markings, are found in other parts of the world.

Surely then it becomes necessary that they should not l>e all arranged under one generic title, but that each

form should have a designation of its own by which it may be at once recognized: this has accordingly

been done by modern systematists.

I have mentioned that the Reed-Bunting resorts to fluviatile districts; and I may now add that it

especially affects bogs, marshes, broads, and the basics of rivers, particularly where the common reed

(Phragmtec communis) grows, and osiers, alders, and wMow, abound. On the banks of the Thames and all

its tributaries, in the fens of Lincolnshire, t ambridgcshirc, Norfolk, and Suffolk, and in all situations where

rank vegetation clothes the sides of water, from one end of England and Wales to the other, the b.rd is found

In Ireland it is a resident species, that island, from the prevailing humidity, remarks Thompson, being well

suited to it. In Scotland it is scarcely less abundant. In the marshy countries of Holland and Belgium no

bird is more frequently met with ; neither is it much less numerous in Germany and all the central parts of

Europe. It also ranges far to the north, in Norway and Sweden. Captain Loche informs us that it is found

ill Algeria; but it was not noticed there by Mr. Tristram and his friends, nor does that gentleman include

it in his list of the birds of Palestine.

' I cannot agree with Macgiilivrny and some other of my cotemporaries when they describe this bird as

shy and difficult of approach ; for I and all my fellow-fisl.ermcn, and, indeed, every one who whiles away a

pleasant hour on the Thames, find it just the reverse. What bird, in fact, which frequents the banks of that

beautiful river can be more nearly approached, or which sits more conspicuously on the hanging branch of

the willow or the upright stem of the osier? Where is there a bird which allows you to get so near while

it is in search of stranded seeds, insects, or small mollusks on the margins of the water, or while sunilariy

occupied on the hard-trodden .«wing-path ? All who have visited such localities must have noticed the

white-necked male Hit before them with a jerking flight, or cross the river at right angles to the neig -

bouring ait. ^ >» ,

In Scotland this bird is said to leave the country during the winter, or, at all events, to become sensibly

scarcer at that period; with us on the Thames, and, I believe, in all our central and southern couut.es, it is

as abundant iu winter as in summer. The greater number remain near water; but a few oceasmiially seek

the hedges of the open fallow or grass fields, and, like other birds, when driven to a strait for food, it wd

resort to the farm-yard; not that grain under ordinary circumstances is an article of its diet, its feeble bill

being better adapted for the seizure of insects, small seeds, and minute shelled mollusks, all of which are

readily found in its usual places of resort, the marsh anti the willow-bed.