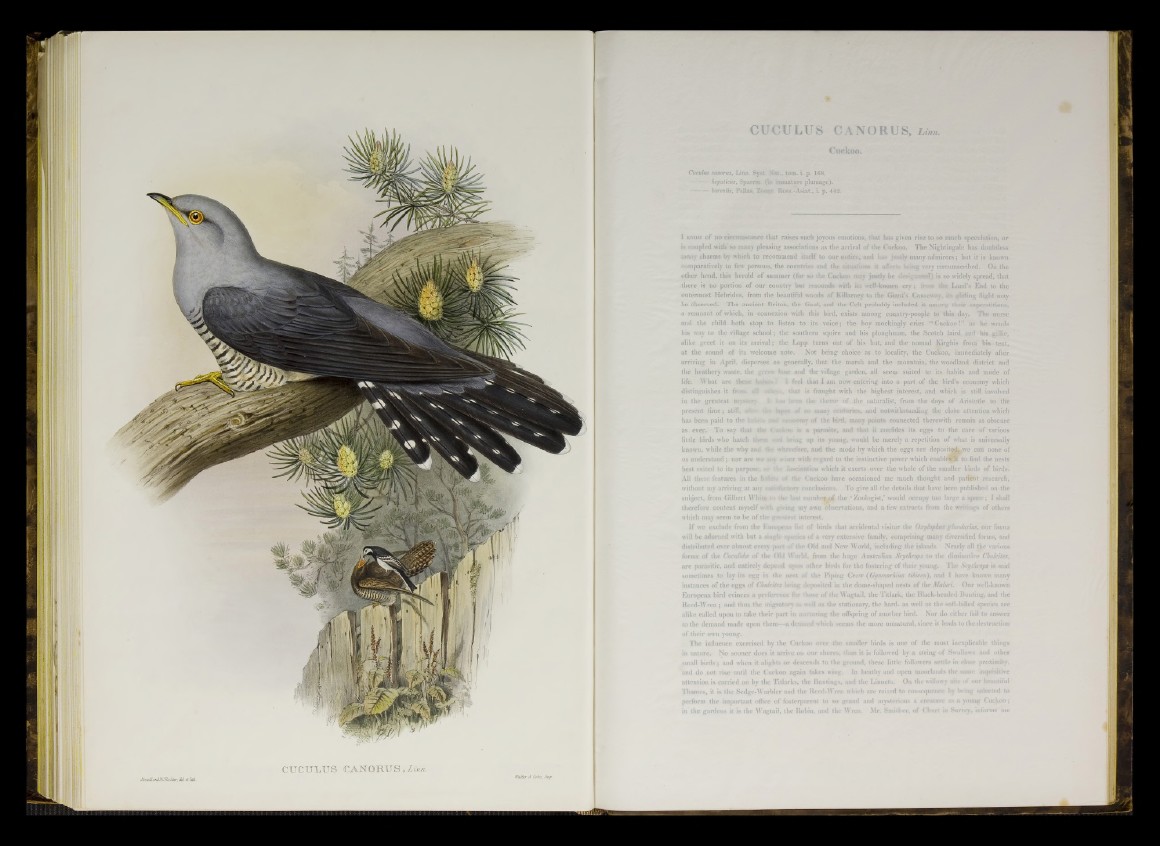

CUCXJLUS CANORUS,iww.

JCauUahìHCRuhàr, id dl& . Wt&tr *Cohl,/n>/>.

CUCULUS CANORUS, ÏÂ ïlll.

Cuckoo.

Cttculus amortis, Linn. Syat. Nîafc,, tom. i. p. 168.

hepaticus, Sparrws. (In immature plumage).

borealis, P allas, Zoogr. Ross.-Àsiat., i. p. 44i

I k n o w of no circumstance that raises such joyous emotions, that has given rise to so much speculation, or

a coupled witli to many pleasing associations as the arrival of the Cuckoo. The Nightingale has doubtless

îiiîvny charms by which to recommend itself to our notice, and has justly many admirers ; but it is known

comparatively to few persons, the countries aud the situations it affects being very circumscribed. On the

other hand, this herald of summer (for so the Cuckoo may justly be dt is so widely spread, that

there is no portion of onr country but resounds with its »veil-known cry ; from the Land's End to the

outermost Hebrides, from the beautiful woods of Kiilarney to the Giant’s Causeway, ite gliding flight may

be observed. The ancient Britoh, the Gaul, and the Celt probably included it among their superstitions,

a remnant of which, in connexion with this bird, exists among country-people to this day. The nurse

and the child both stop to listen to its voice; the boy mockingly cries “ Cuckoo!” as he wends

his way to the village school ; the southern squire and his ploughman, the Scotch laird and bis gillie,

alike greet it on its arrival ; the Lapp turns out of his hut, and the nomad Kirghis from his teut,

at the sound of its welcome note. Not being choice as to locality, ' the Cuckoo, immediately after

arriving in April, disperses so generally, that the marsh and the mountain, the woodland district and

thè heathery waste, the green bum and the village garden, all seem suited to its habits and mode of

life. What are these i-v ’ i feel that I am now entering into a part of the bird’s economy which

distinguishes it from a& «fot»*. that is fraught with the highest interest, and which is still involved

in the greatest tuv>«-wy I hm been the theme of the naturalist, from the days of Aristotle to the

present time ; still, ■ the fame« of so many centuries, and notwithstanding the close attention which

has been paid to the ì-.ó:.-- - ¿«di actmom? of the bird, many points connected therewith remain as obscure

as ever. To say that the Gwcfeoo is a parasite, and that it confides its eggs to the care of various

little birds who hatch them bring up its young, would be merely a repetition of what is universally

known, while the why and the wherefore, and the mode by which the eggs are deposit^,.we can none of

us understand ; nor are wv <*«_* wiser with regard to the instinctive power which enablésit to find the bests

best suited to its purpose, or the fascination which it exerts over the whole of the smaller kinds of birds.

AU these features in the bahtt* of Hie Cuckoo have occasioned me much thought and patient research,

without my arriving.at any <■>.' -feeiorv conclusions. To give all the details that have been published on the

subject, from Gilbert Whitt m the last number of the * Zoologist,’ would occupy too large a space ; I shall

therefore content myself with giving my own Observations, and a few extracts from the writings of others

which may seem to be of the greatest interest.

If we exclude from the European list of birds that accidental visitor the Qxylopkns gtandarius, our fauna

will be adorned with but a single species of a very extensive family, comprising many diversified forms, and

distributed over almost every part of the Old and New World, including the islands. Nearly all the various

forms of the Cuculidee of the Old World, from the huge Australian Scythrops to the diminutive Clalcites,

are parasitic, and entirely depend upon other birds for the fostering of their young. The Seytfirops is said

sometimes to lay its egg in the nest of the Piping Grow (Gymnorhina tibicen), and I have known many

instances of the eggs of Chalcitet being deposited in the dome-shaped nests of the Maluri. Our well-known

European bird evinces a preference for those of the Wagtail, the Titlark, the Black-headed Bunting, and the

Reed-Wren ; and thus the migratory as well as the stationary, the hard- as well as the soft-billed species are

alike called upon to take their part in nurturing the offspring of another bird. Nor do either fail to answer

to the demand made upon them—à demand which seems the more unnatural, since it leads to the destruction

of their own young.

The influence exercised by the Cuckoo over the smaller birds is one of the most inexplicable things

in nature. No sooner does it arrive on our shores, than it is followed by a string of Swallows and other

small birds ; and when it alights or descends to the ground, these little followers settle in close proximity,

and do not rise • until the Cuckoo again takes wing. In heathy and open moorlands the same inquisitive

attention is carried on by the Titlarks, thé Buntings, and the Linnets. On the willowy ait« of our beautiful

Thames, it is the Sedge-Warbler and the Recd-Wren which are raised to consequence by being selected to

perform the important office of fosterparent to so grand and mysterious a creature as a young Cuckoo ;

in the gardens it is the Wagtail, the Robin, and the Wren. Mr. Smither, of Churt in Surrey, informs me