On August 28th we made a fresh start, and, with

no anxiety about triangulation, completed a sixteen-

mile march. The caravan, however, did a much longer

round, as Khalik supposed that he had found a short

cut, and ended by boxing the party up in a rocky

ravine.

Food now began to run short, and we were able to

discriminate between our followers, all of whom had

previously seemed to us to be much of a muchness;

there is nothing like a little hardship and privation to

bring out the good and bad qualities of a man. Of

the Ladakis I have already spoken—they were altogether

excellent. Three out of the four Kashmiris

were worse than useless; Sumdoo of Wataila, one of

the cooks, was an admirable servant—his compatriots

were the reverse; on the whole, the Argoons were

good—two of them, however, rejoicing in the names of

Ghulam Nabi and Mahi Din, were first-class scoundrels

and bosom friends of Khalik.

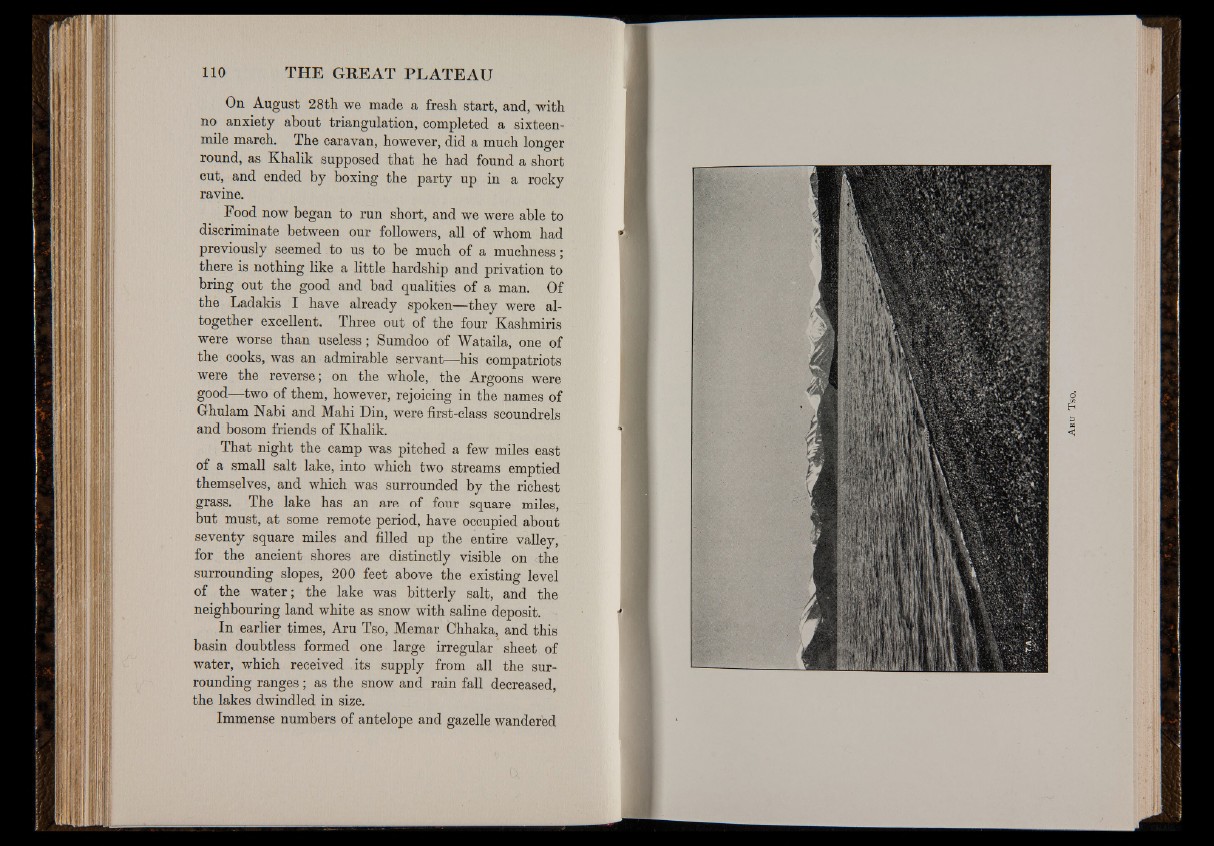

That night the camp was pitched a few miles east

of a small salt lake, into which two streams emptied

themselves, and which was surrounded by the richest

grass. The lake has an are of four square miles,

but must, at some remote period, have occupied about

seventy square miles and filled up the entire valley,

for the ancient shores are distinctly visible on the

surrounding slopes, 200 feet above the existing level

of the water; the lake was bitterly salt, and the

neighbouring land white as snow with saline deposit.

In earlier times, Aru Tso, Memar Chhaka, and this

basin doubtless formed one large irregular sheet of

water, which received its supply from all the surrounding

ranges; as the snow and rain fall decreased,

the lakes dwindled in size.

Immense numbers of antelope and gazelle wandered