one feels sure the camp should be, only to discover

not a sign of man or beast; shouting and firing of

shots are of no avail, there is nothing for it but to

brace oneself up to climb yet another hill, from which

to sweep the landscape once more with the glasses.

At last it may be that a pony, a thin column of

smoke, or a figure outlined against the sky is descried,

and then the weary tramp is recommenced. One

arrives in camp sulky and angry ; everyone is to blame

(except, of course, oneself); everything looks wrong.

Gradually, however, shelter, warmth and food begin

to have their effect; the aspect of things alters, all

is forgiven—after all, the men were rig h t; one should

have known that they would halt at this, the best

of all possible spots; and eventually tranquillity is

restored.

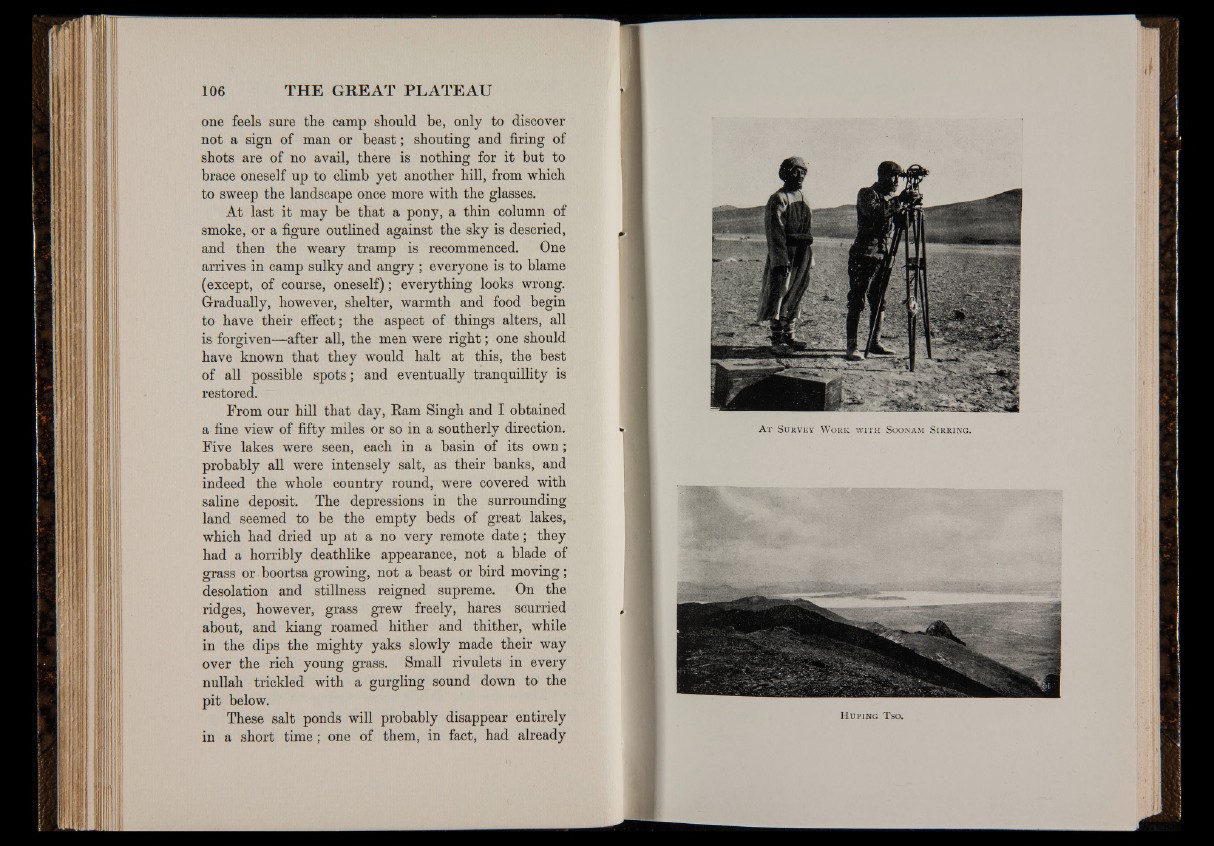

From our hill that day, Ram Singh and I obtained

a fine view of fifty miles or so in a southerly direction.

Five lakes were seen, each in a basin of its own;

probably all were intensely salt, as their banks, and

indeed the whole country round, were covered with

saline deposit. The depressions in the surrounding

land seemed to be the empty beds of great lakes,

which had dried up at a no very remote d ate ; they

had a horribly deathlike appearance, not a blade of

grass or boortsa growing, not a beast or bird moving;

desolation and stillness reigned supreme. On the

ridges, however, grass grew freely, hares scurried

about, and kiang roamed hither and thither, while

in the dips the mighty yaks slowly made their way

over the rich young grass. Small rivulets in every

nullah trickled with a gurgling sound down to the

pit below.

These salt ponds will probably disappear entirely

in a short time; one of them, in fact, had already

H u p in g T so.