sents of money, and such treatment worked wonders.

Even to the end of our journey the fact that we paid

for everything used, and also gave money to those who

deserved it, naturally created great surprise amongst

these people. The usual custom in Tibet is that

when an official, or any swashbuckler, arrives at a

village, not only does he take everything without

payment that he can lay his hands on, but he expects

also to be presented with money, sheep, ponies, etc.

The law demands, for instance, that when the Chinese

Amban travels about the country, the districts he

visits must pay him 600 rupees a day, so long as

he is with them, not one penny of which do they ever

see again. Truly the axiom of “ speeding the parting

guest ” is most appropriate here.

On the road the following day, a pathetic drama

in natural history was enacted before our eyes.

Crossing the path about 150 yards ahead of us was

a hawk stooping at a hoopoo, the long-beaked little

bird so well known in India. Time after time the

hawk missed his quarry, but each stoop brought him

nearer and nearer to his prey. Catching sight of

the ponies, the panting hoopoo changed his course,

and headed straight for them. Twice more he defeated

the pursuer, but only by a hair’s breadth, and

fluttering up to us, alighted on the crupper of Ka

Sang’s saddle, where he hung panting and shaking.

On a man trying to catch him, he flew from saddle

to saddle, refusing to quit this place of refuge until

the dreaded enemy was out of sight. He then fluttered

into a nullah and vanished.

Before reaching our destination a river of considerable

size had to be forded, as the one and only

bridge which originally stood here had been washed

away. On either bank, however, men were in attendL

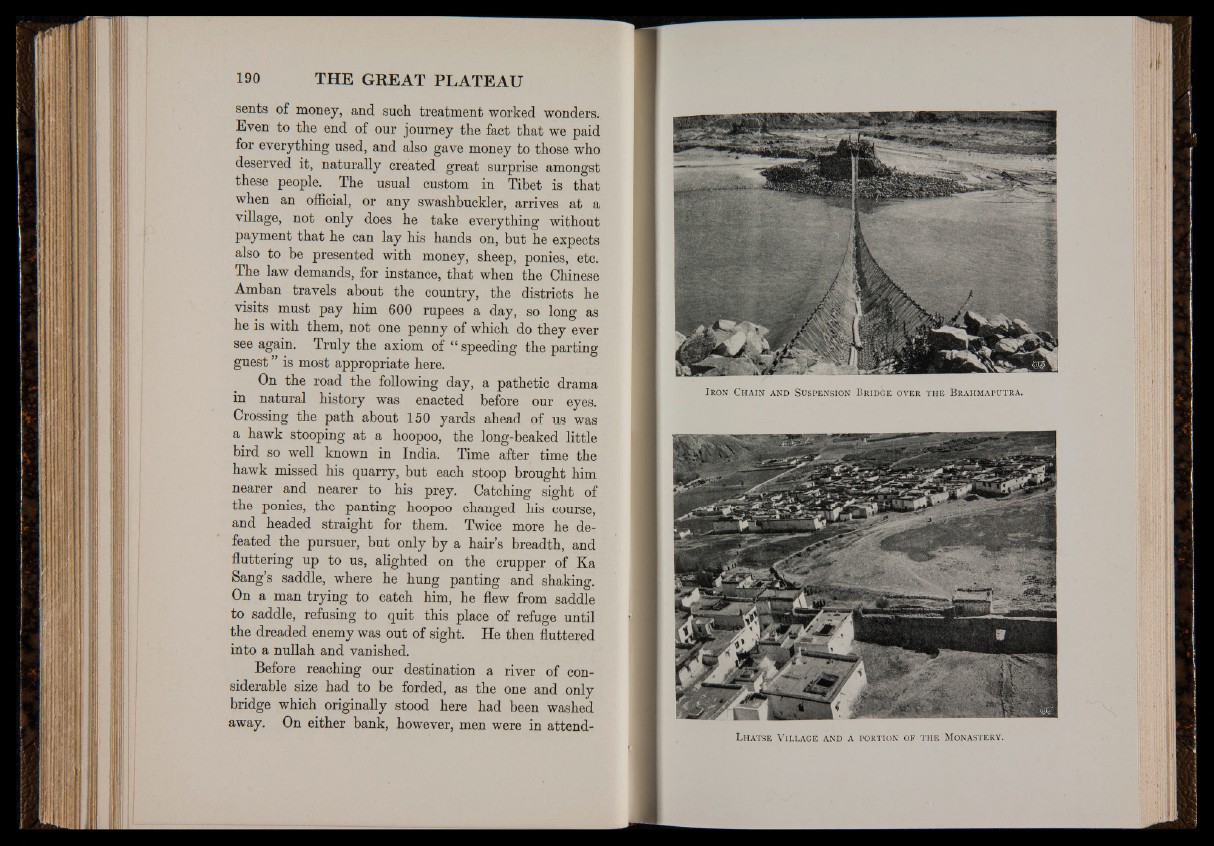

h a t s e V il l a g e a n d a p o r t io n o f t h e M o n a s t e r y .