of the coming incident if you will remember the bitter,

frost-laden south wind blowing all day with increasing

strength beneath a hard ash-grey sky.

Just when the Tibetan wall had become clearly

visible in the distance, a messenger, riding forward in

haste, announced the coming of the leading men of the

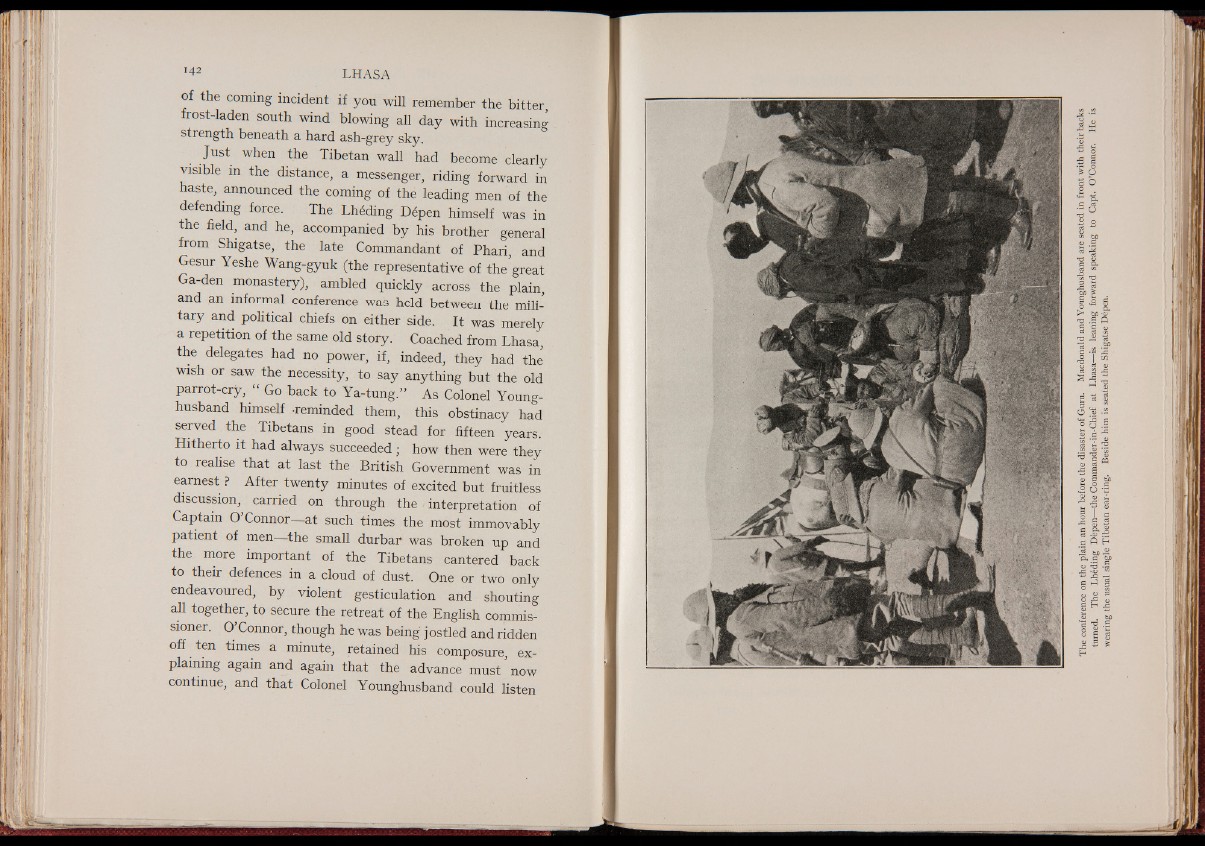

defending force. The Lheding Depen himself was in

the field, and he, accompanied by his brother general

from Shigatse, the late Commandant of Phari, and

Gesur Yeshe Wang-gyuk (the representative of the great

Ga-den monastery), ambled quickly across the plain,

and an informal conference was held between the military

and political chiefs on either side. It was merely

a repetition of the same old story. Coached from Lhasa,

the delegates had no power, if, indeed, they had the

wish or saw the necessity, to say anything but the old

parrot-cry, “ Go back to Ya-tung.” As Colonel Young-

husband himself -reminded them, this obstinacy had

served the Tibetans in good stead for fifteen years.

Hitherto it had always succeeded; how then were they

to realise that at last the British Government was in

earnest ? After twenty minutes of excited but fruitless

discussion,^ carried on through the interpretation of

Captain O Connor— at such times the most immovably

patient of men— the small durbar was broken up and

the more important of the Tibetans cantered back

to their defences in a cloud of dust. One or two only

endeavoured, by violent gesticulation and shouting

all together, to secure the retreat of the English commissioner.

O’Connor, though he was being jostled and ridden

off ten times a minute, retained his composure, explaining

again and again that the advance must now

continue, and that Colonel Younghusband could listen