Jelep la, and away to the south-west Ling-tu, on the

crest of the 6,000 feet precipice up which the road is

zigzagged, can be seen in the clear air. The Jelep Pass

itself is hidden by the bulk of the range, though only

three miles away. A little lake lies frozen in the stony

bowl up the sides of which we have just come. Far

below its edge falls another mighty hollow, and yet we

do not see a blade or leaf. Only beyond and below,

peering through one of the little crevasses in the ringed

hills, there is the dark mantle of the Sikkim woods. One

turns one’s back upon it for the last time, and gains the

summit, where three heaps of stones, piled b y pious

travellers, support a flagged bush, the usual ornament of

every pass in the country. One takes another step, and

one is in the Chumbi Valley.

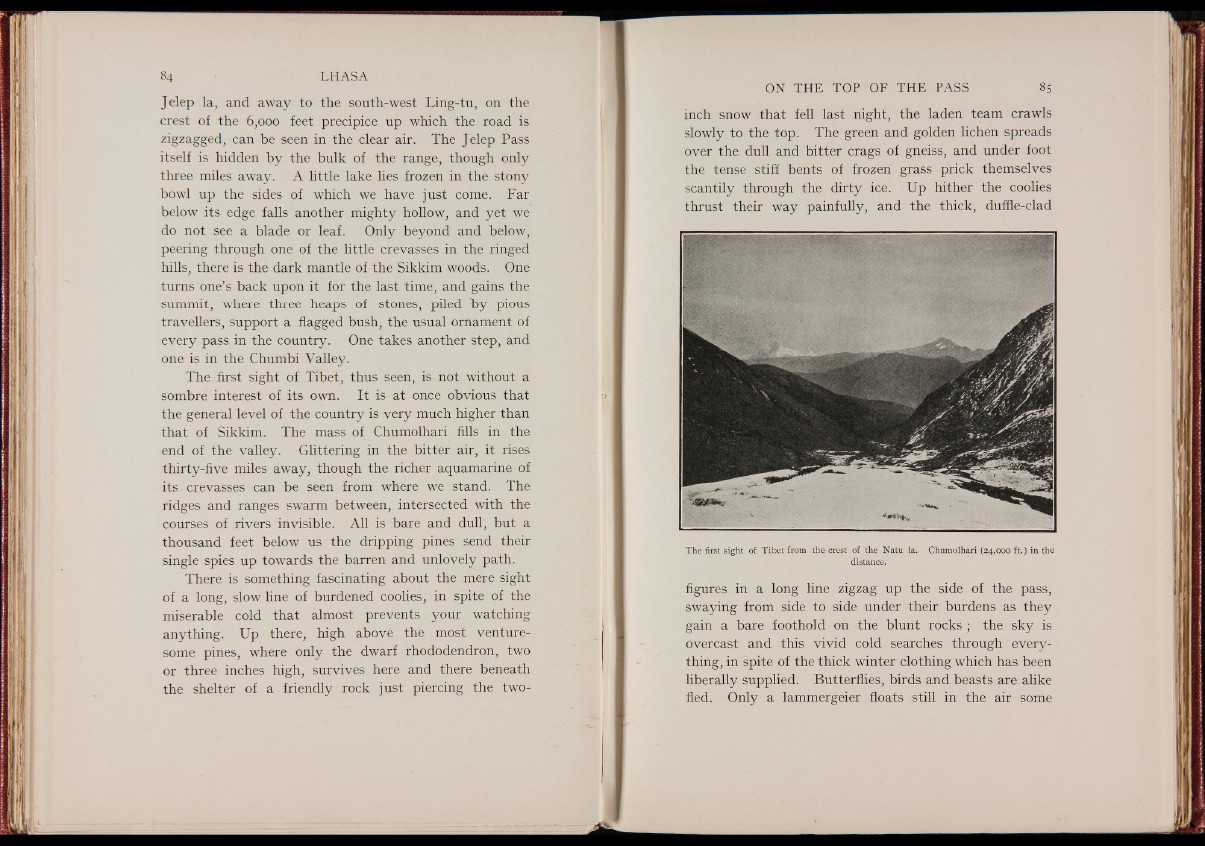

The first sight of Tibet, thus seen, is not without a

sombre interest of its own. It is at once obvious that

the general level of the country is very much higher than

that of Sikkim. The mass of Chumolhari fills in the

end of the valley. Glittering in the bitter air, it rises

thirty-five miles away, though the richer aquamarine of

its crevasses can be seen from where we stand. The

ridges and ranges swarm between, intersected with the

courses of rivers invisible. All is bare and dull, but a

thousand feet below us the dripping pines send their

single spies up towards the barren and unlovely path.

There is something fascinating about the mere sight

of a long, slow line of burdened coolies, in spite of the

miserable cold that almost prevents your watching

anything. Up there, high above the most venturesome

pines, where only the dwarf rhododendron, two

or three inches high, survives here and there beneath

the shelter of a friendly rock just piercing the twoinch

snow that fell last night, the laden team crawls

slowly to the top. The green and golden lichen spreads

over the dull and bitter crags of gneiss, and under foot

the tense stiff bents of frozen grass prick themselves

scantily through the dirty ice. Up hither the coolies

thrust their way painfully, and the thick, duffle-clad

The first sight of Tibet from the crest of the Natu la. Chumolhari (24,000 ft.) in the

distance.

figures in a long line zigzag up the side of the pass,

swaying from side to side under their burdens as they

gain a bare foothold on the blunt rocks ; the sky is

overcast and this vivid cold searches through everything,

in spite of the thick winter clothing which has been

liberally supplied. Butterflies, birds and beasts are alike

fled. Only a lammergeier floats still in the air some