strength, recording from his birth, passage by passage,

the events of his momentous life. Now these were

painted in the happy days before Chandra Das came.

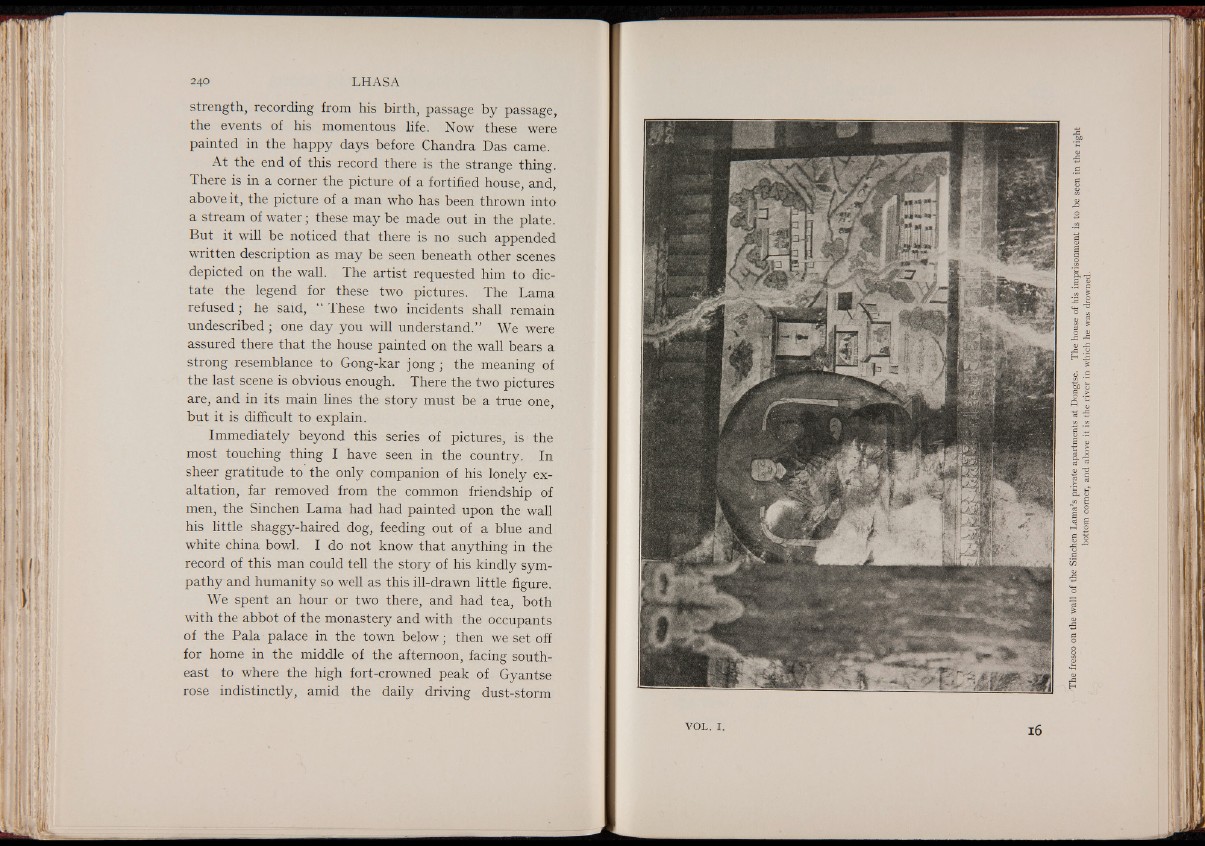

At the end of this record there is the strange thing.

There is in a corner the picture of a fortified house, and,

above it, the picture of a man who has been thrown into

a stream of water; these may be made out in the plate.

But it will be noticed that there is no such appended

written description as may be seen beneath other scenes

depicted on the wall. The artist requested him to dictate

the legend for these two pictures. The Lama

refused; he said, “ These two incidents shall remain

undescribed; one day you will understand.” We were

assured there that the house painted on the wall bears a

strong resemblance to Gong-kar jon g ; the meaning of

the last scene is obvious enough. There the two pictures

are, and in its main lines the story must be a true one,

but it is difficult to explain.

Immediately beyond this series of pictures, is the

most touching thing I have seen in the country. In

sheer gratitude to the only companion of his lonely exaltation,

far removed from the common friendship of

men, the Sinchen Lama had had painted upon the wall

his little shaggy-haired dog, feeding out of a blue and

white china bowl. I do not know that anything in the

record of this man could tell the story of his kindly sympathy

and humanity so well as this ill-drawn little figure.

We spent an hour or two there, and had tea, both

with the abbot of the monastery and with the occupants

of the Pala palace in the town below; then we set off

for home in the middle of the afternoon, facing southeast

to where the high fort-crowned peak of Gyantse

rose indistinctly, amid the daily driving dust-storm

v o l . I