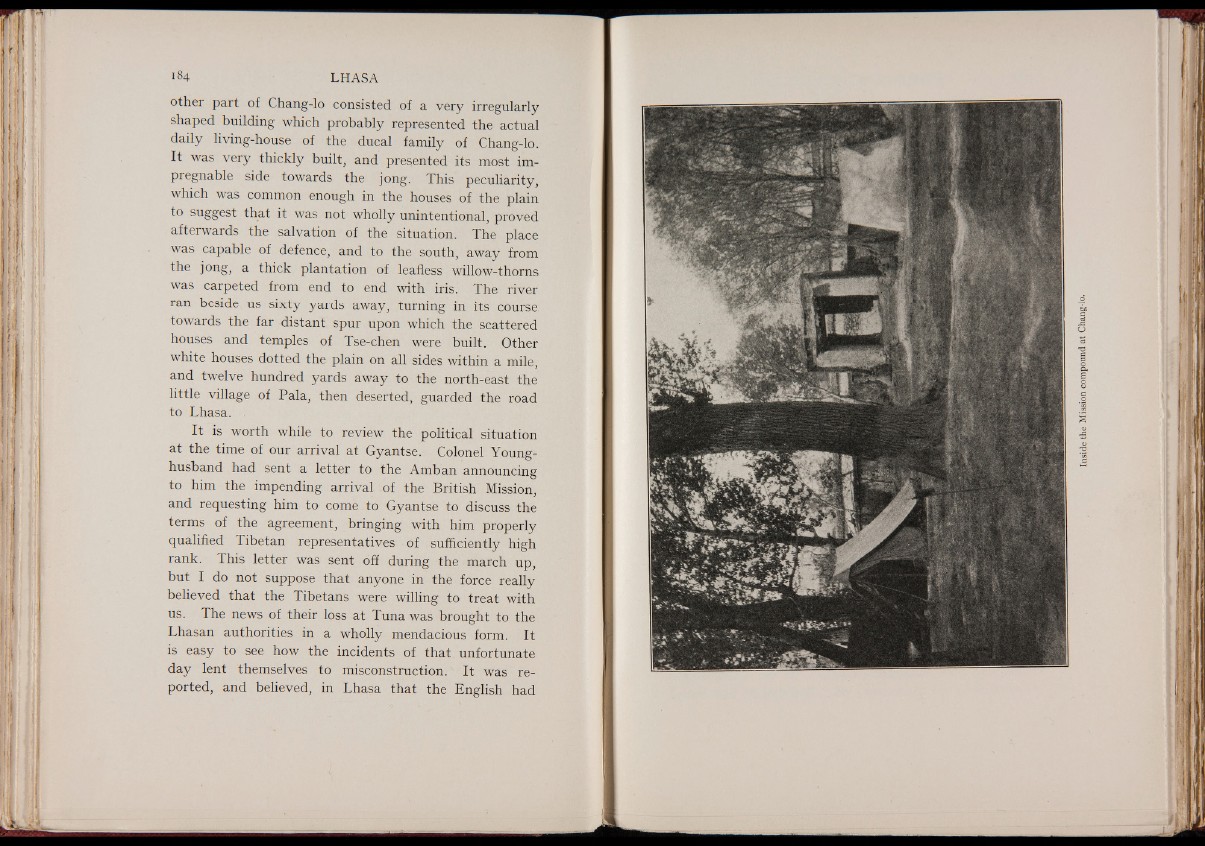

other part of Chang-lo consisted of a very irregularly

shaped building which probably represented the actual

daily living-house of the ducal family of Chang-lo.

It was very thickly built, and presented its most impregnable

side towards the jong. This peculiarity,

which was common enough in the houses of the plain

to suggest that it was not wholly unintentional, proved

afterwards the salvation of the situation. The place

was capable of defence, and to the south, away from

the jong, a thick plantation of leafless willow-thorns

was carpeted from end to end with iris. The river

ran beside us sixty yards away, turning in its course

towards the far distant spur upon which the scattered

houses and temples of Tse-chen were built. Other

white houses dotted the plain on all sides within a mile,

and twelve hundred yards away to the north-east the

little village of Pala, then deserted, guarded the road

to Lhasa. .

It is worth while to review the political situation

at the time of our arrival at Gyantse. Colonel Young-

husband had sent a letter to the Amban announcing

to him the impending arrival of the British Mission,

and requesting him to come to Gyantse to discuss the

terms of the agreement, bringing with him properly

qualified Tibetan representatives of sufficiently high

rank. This letter was sent off during the march up,

but I do not suppose that anyone in the force really

believed that the Tibetans were willing to treat with

us. The news of their loss at Tuna was brought to the

Lhasan authorities in a wholly mendacious form. It

is easy to see how the incidents of that unfortunate

day lent themselves to misconstruction. It was reported,

and believed, in Lhasa that the English had