Other more public charms against evil are the

chortens or cairns which piety or terror has set up at

small intervals along the road to be a continual nuisance

to the impious traveller. Like the “ islands ” in Piccadilly

or the Strand, they may only be passed to the

left, and their position on the edge of a cliff often renders

this in one direction a hazardous proceeding. There

are, of course, no carts or wheeled vehicles of any kind

in Tibet, or this superstition would long ago have become

extinguished through sheer necessity. As it is, the

chorten remains till the cliff itself falls, but to the last

there is generally foothold on which to climb round the

outside of a cairn. It may be noted as a psychological

curiosity that, after living in the country for a few

months, the least thoughtful man in the force usually

adopted this superstition as he walked along, though,

of course, when riding it is not unnatural for Englishmen.

Here and there one finds long walls, composed for

the most part of inscribed stones ; these mendangs or

manis represent the accretions of many years, and some

in Tibet are reported to be half a mile in length. They

do not, however, assume the importance in the province

of U that they possess farther to the west. To other

pious memorials also the passer-by adds his contribution

of a stone. A few white pebbles of quartzite carefully

selected from the neighbouring stone-strewn field will

acquire for him no small merit if heaped together in a

little pyramid, or piled with careful balance one on the

top of another. Prayer-wheels offer their fluted axles to

the hand of the traveller in long rows, hung up conveniently

beside the wall of a house. The poorest may

thus accumulate merit. I have before referred to the

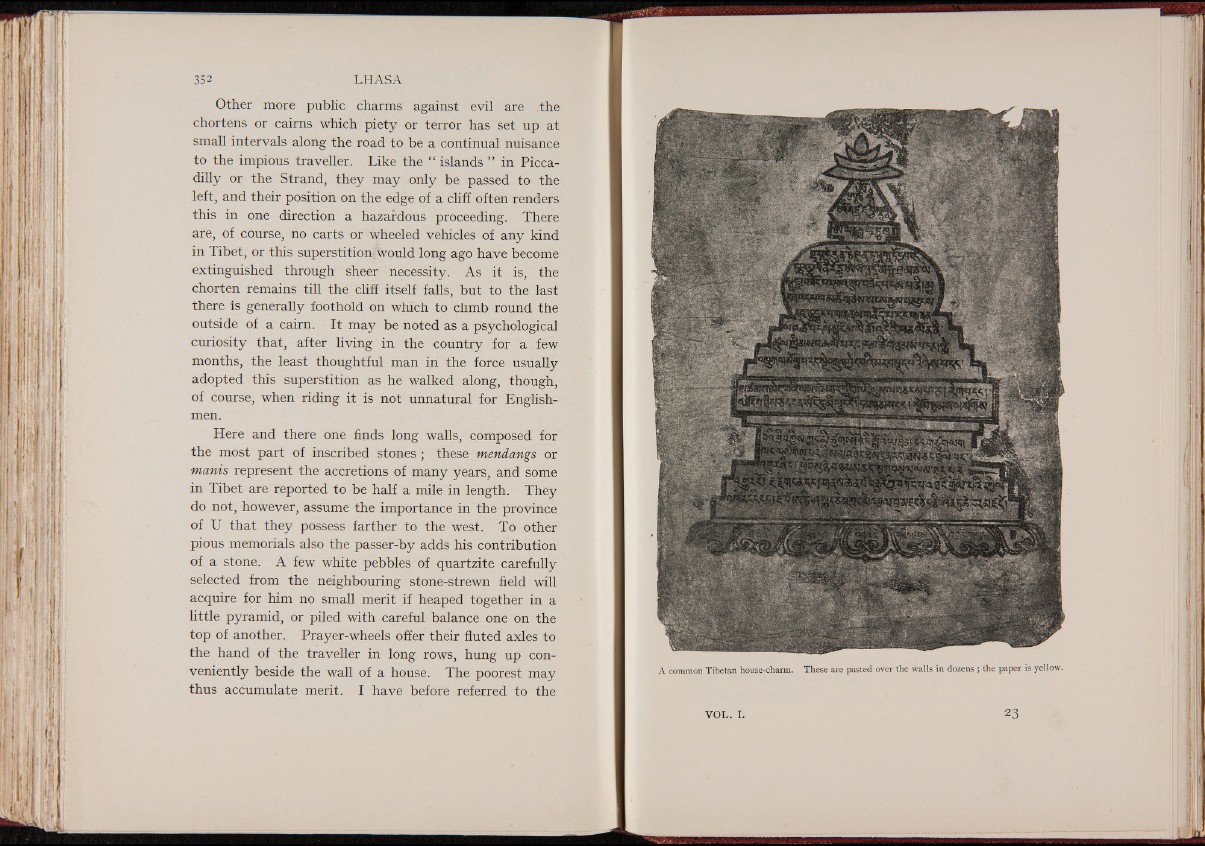

A common Tibetan house-charm. These are pasted over the walls in dozens ; the paper is yellow.

VO L. I. 23

¡U n i