and useless life. He takes no interest and no share

in the doings of the little village at his feet. Their

prosperity or their trouble, their sickness or their health,

are alike of no consequence to him. He does not even

pretend to pray for them. He only comes among them

for the purpose of silently collecting the pious offerings

of those whose charity is as meaningless as his own life.

From Rinchengong the road runs northward along

the right bank of the river, flat and straight to Chema.

Half a mile before Chema is reached, the new road

over the Natu la descends between two narrow, stone-

built walls. Chema (which is pronounced “ Pe-ma ” by

the people of Gangtok, to whom this little place is of

some repute because within its boundaries the two

roads from Gangtok to Chumbi and the north descend)

is a town as like Rinchengong as one pea is like another.

The presiding Kazi is Norzan, and his house is the first

that one meets coming down into the town by the

valley of the Yak la. Across a triangular market-place

is a shrine with a long row of small prayer wheels, framed

behind a palisade against the wall. These the pious

inhabitants turn idly as they walk past on their way to

the bridge, and the dirt of many generations of Tibetan

hands has almost clogged the flutings of the handles.

Under an overhanging balcony on the right was a huge

Tibetan mastiff with a red woollen collar, so chained up

to the rafters above that only immediately below the

knot can he place all four legs on the ground at once.

He is, of course, a bad-tempered, mangy brute. But

he is, perhaps, of interest as being, like the hermit’s cave,

the first of an interminable number of his fellows in

Tibet. There is a curiosity nailed up against a wooden

pillar over his head, in the shape of a six-pointed shao

horn.* Mr. Claude White has its fellow in the Residency

at Gangtok. Across the bridge are two or three chortens,

beneath towering prayer poles, attracting the eyes, and

distracting the path of the good people, who may only

pass round them from left to right.

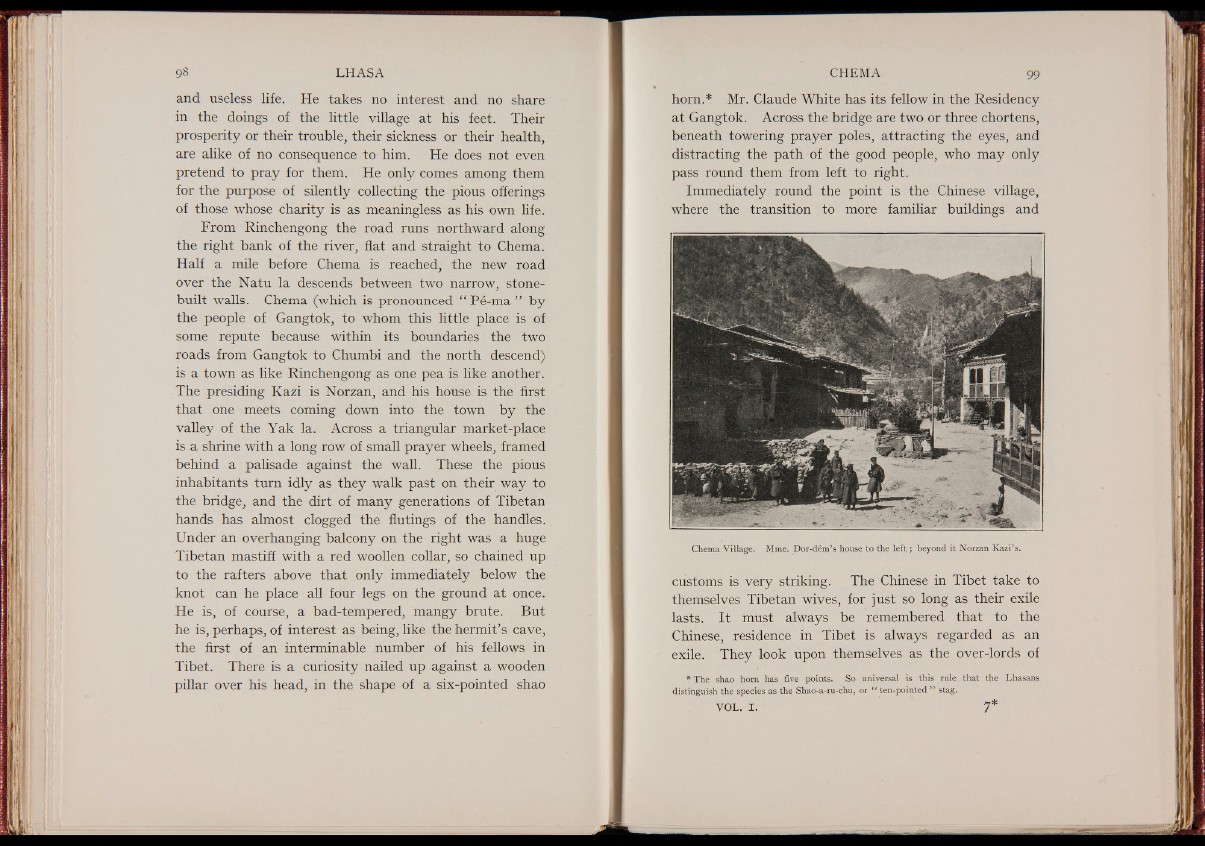

Immediately round the point is the Chinese village,

where the transition to more familiar buildings and

Chema Village. Mme. Dor-d&n’s house to the l e f t ; beyond it Norzan K a zi’s.

customs is very striking. The Chinese in Tibet take to

themselves Tibetan wives, for just so long as their exile

lasts. It must always be remembered that to the

Chinese, residence in Tibet is always regarded as an

exile. They look upon themselves as the over-lords of

* The shao horn has five points. So universal is this rule that the Lhasans

distinguish the species as the Shao-a-ru-chu, or “ ten-pointed ” stag.

VOL. I . 7 *