had encroached upon our territory in Sikkim, they

had established a customs post at Giao-gong, fifteen

miles inside the frontier, and had forbidden British

subjects to pass their outposts there ; they had thrown

down the boundary pillars which had been set up along

the undisputed water-shed between the Tista and the

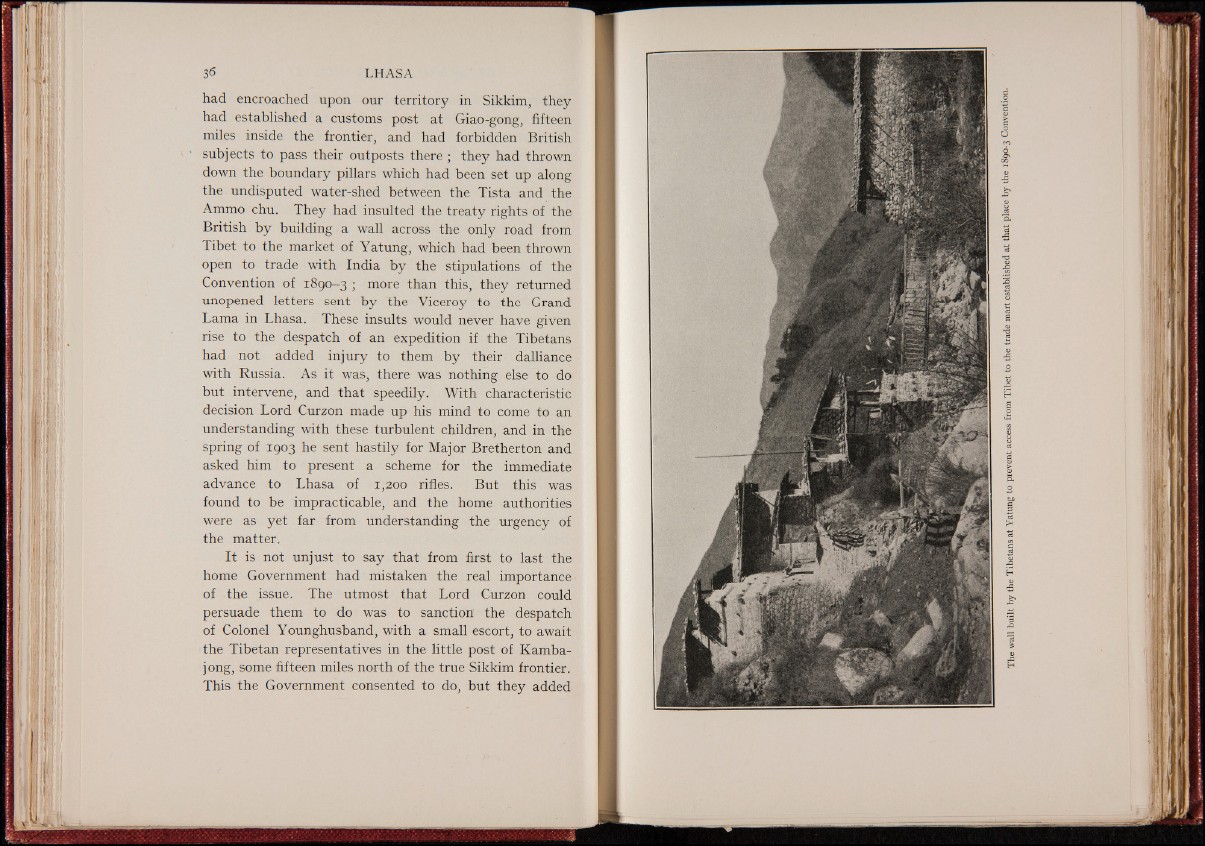

Ammo chu. They had insulted the treaty rights of the

British by building a wall across the only road from

Tibet to the market of Yatung, which had been thrown

open to trade with India by the stipulations of the

Convention of 1890—3 ; more than this, they returned

unopened letters sent by the Viceroy to the Grand

Lama in Lhasa. These insults would never have given

rise to the despatch of an expedition if the Tibetans

had not added injury to them by their dalliance

with Russia. As it was, there was nothing else to do

but intervene, and that speedily. With characteristic

decision Lord Curzon made up his mind to come to an

understanding with these turbulent children, and in the

spring of 1903 he sent hastily for Major Bretherton and

asked him to present a scheme for the immediate

advance to Lhasa of 1,200 rifles. But this was

found to be impracticable, and the home authorities

were as yet far from understanding the urgency of

the matter.

It is not unjust to say that from first to last the

home Government had mistaken the real importance

of the issue. The utmost that Lord Curzon could

persuade them to do was to sanction the despatch

of Colonel Younghusband, with a small escort, to await

the Tibetan representatives in the little post of Kamba-

j ong, some fifteen miles north of the true Sikkim frontier.

This the Government consented to do, but they added