strangely alike. Neither here nor elsewhere in Tibet

do the men grow moustaches or beards .; the utmost

that one ever sees is a thin fringe of scanty hair marking

the lips, or pointing the chin of a high official. It cannot

be claimed that Tibetan ladies look beautiful. It is

of course difficult to say what the effect would be if

some of them were thoroughly washed. As it is, they

exist from the cradle, or what corresponds to it, to the

stone slab on which their dead bodies are hacked to

pieces, without a bath or even a partial cleansing

of any kind. One could imagine that they were of a

tint almost as dark as a Gurkha, but this is by no means

the case. In spite of the dirt, wherever the bodies

are protected by clothes the skin remains of an ivory

whiteness, which is indistinguishable from that of

the so-called white races. At times also accident,

perhaps in the shape of rain, has the effect of removing

an outer film of dirtiness, and then it is quite

clear that Tibetan girls, until they are two or three

and twenty, have a complexion. Of course the habit

of the race, of besmearing the forehead, cheeks, and

nose with dark crimson kutch, which blackens as it

dries, militates against any display of beauty. The

origin of this strange custom is, like most facts and

theories about Tibet, the subject of hot dispute. Some

contend that it originally marked the married women

only : some will have it, and there seems some evidence

in their favour, that this disfigurement was intentionally

introduced in order to save the ladies of Tibet from the

sin of vanity, and incidentally, also, to reduce the chances

of_ young men’s infatuation. The third and more

prosaic explanation is that it is done to mitigate the

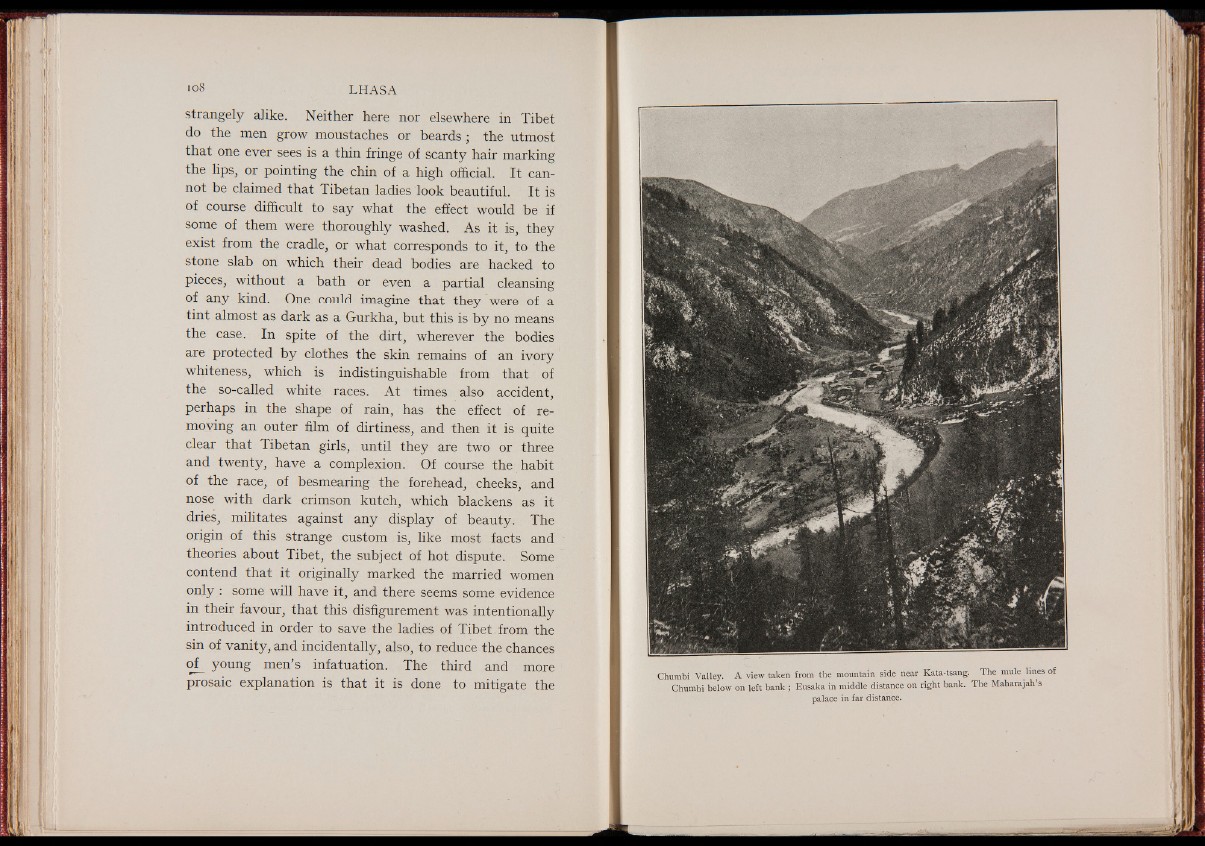

Chumbi Valley. A view taken from the mountain side near Kata-tsang. The mule lines of

Chumbi below on left bank ; Eusaka in middle distance on right bank. The Maharajah’ s

palace in far distance.