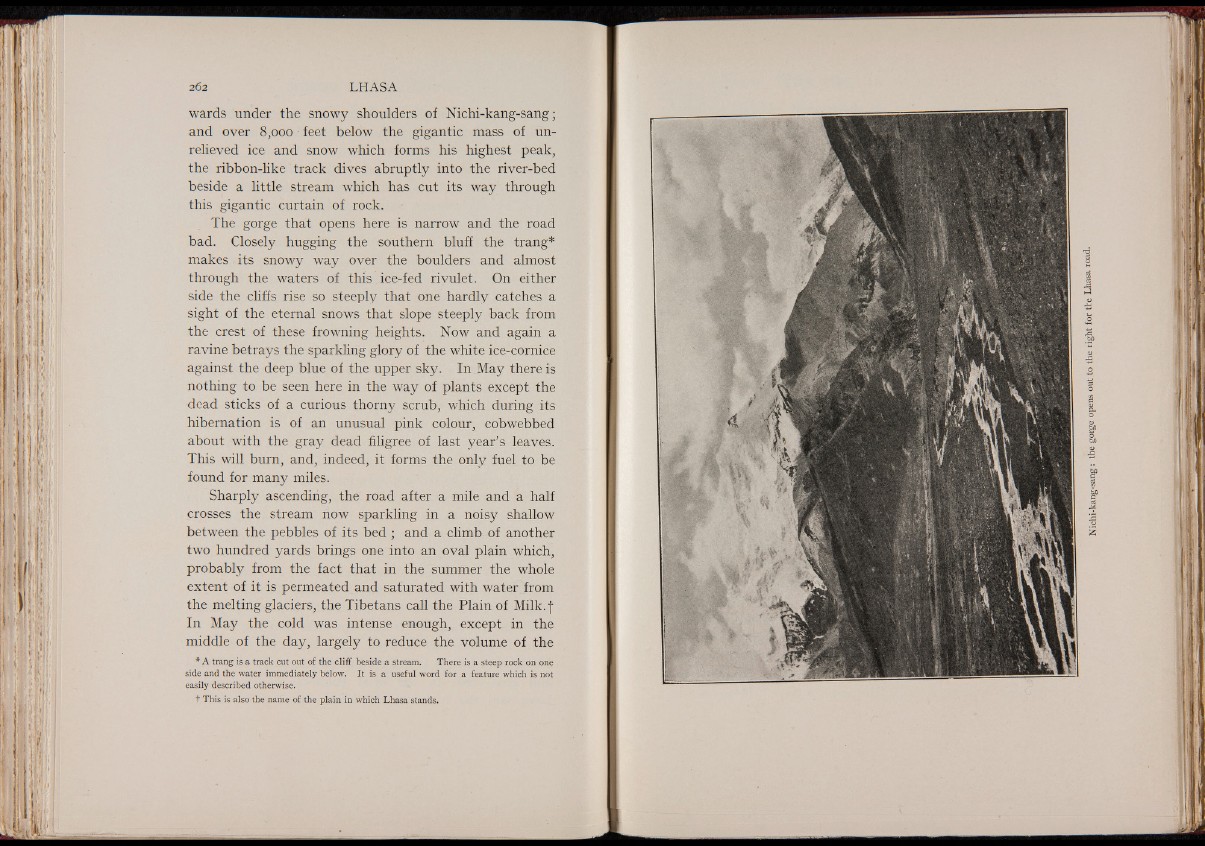

wards under the snowy shoulders of Nichi-kang-sang;

and over 8,000 feet below the gigantic mass of unrelieved

ice and snow which forms his highest peak,

the ribbon-like track dives abruptly into the river-bed

beside a little stream which has cut its way through

this gigantic curtain of rock.

The gorge that opens here is narrow and the road

bad. Closely hugging the southern bluff the trang*

makes its snowy way over the boulders and almost

through the waters of this ice-fed rivulet. On either

side the cliffs rise so steeply that one hardly catches a

sight of the eternal snows that slope steeply back from

the crest of these frowning heights. Now and again a

ravine betrays the sparkling glory of the white ice-cornice

against the deep blue of the upper sky. In May there is

nothing to be seen here in the way of plants except the

dead sticks of a curious thorny scrub, which during its

hibernation is of an unusual pink colour, cobwebbed

about with the gray dead filigree of last year’s leaves.

This will burn, and, indeed, it forms the only fuel to be

found for many miles.

Sharply ascending, the road after a mile and a half

crosses the stream now sparkling in a noisy shallow

between the pebbles of its b ed ; and a climb of another

two hundred yards brings one into an oval plain which,

probably from the fact that in the summer the whole

extent of it is permeated and saturated with water from

the melting glaciers, the Tibetans call the Plain of Milk.f

In May the cold was intense enough, except in the

middle of the day, largely to reduce the volume of the

* A trang is a track cut out of the c liff beside a stream. There is a steep rock on one -

side and the water immediately below. It is a useful word for a feature which is not

easily described otherwise.

t This is also the name of the plain in which Lhasa stands.