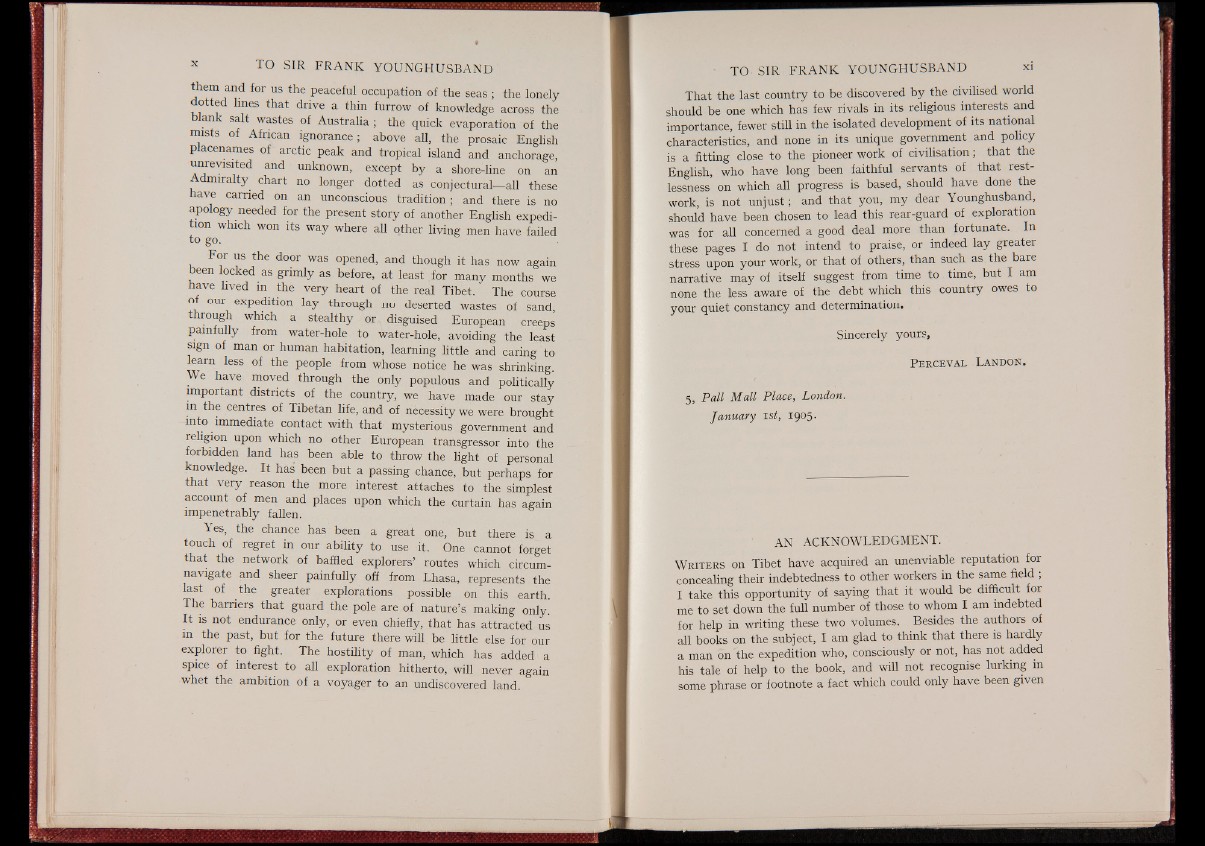

them and for us the peaceful occupation of the seas ; the lonely

dotted lines that drive a thin furrow of knowledge across the

an salt wastes of Australia ; the quick evaporation of the

mists of African ignorance; above all, the prosaic English

placenames of arctic peak and tropical island and anchorage,

unrevisited and unknown, except by a shore-line on an

Admiralty chart no longer dotted as conjectural— all these

have carried on an unconscious tradition; and there is no

apology needed for the present story of another English expedition

which won its way where ah other living men have failed

to go.

For us the door was opened, and though it has now again

been locked as grimly as before, at least for many months we

have lived m the very heart of the real Tibet. The course

of our expedition lay through no deserted wastes of sand,

through which a stealthy or disguised European creeps

painfully from water-hole to water-hole, avoiding the least

sign of man or human habitation, learning little and caring to

learn less of the people from whose notice he was shrinking.

We have moved through the only populous and politically

important districts of the country, we have made our stay

in the centres of Tibetan life, and of necessity we were brought

into immediate contact with that mysterious government and

religion upon which no other European transgressor into the

forbidden land has been able to throw the light of personal

knowledge. It has been but a passing chance, but perhaps for

that very reason the more interest attaches to the simplest

account of men and places upon which the curtain has again

impenetrably fallen.

le s , the chance has been a great one, but there is a

touch of regret in our ability to use it. One cannot forget

that the network of baffled explorers’ routes which circumnavigate

and sheer painfully off from Lhasa, represents the

last of the greater explorations possible on this earth.

The barriers that guard the pole are of nature’s making only.

It is not endurance only, or even chiefly, that has attracted us

m the past, but for the future there will be little else for our

explorer to fight. The hostility of man, which has added : a

spice of interest to all exploration hitherto, will never again

whet the ambition of a voyager to an undiscovered land.

That the last country to be discovered by the civilised world

should be one which has few rivals in its religious interests and

importance, fewer still in the isolated development of its national

characteristics, and none in its unique government and policy

is a fitting close to the pioneer work of civilisation; that the

English, who have long been faithful servants of that restlessness

on which all progress is based, should have done the

work, is not unjust; and that you, my dear Younghusband,

should have been chosen to lead this rear-guard of exploration

was for all concerned a good deal more than fortunate. In

these pages I do not intend to praise, or indeed lay greater

stress upon your work, or that of others, than such as the bare

narrative may of itself suggest from time to time, but I am

none the less aware of the debt which this country owes to

your quiet constancy and determination.

Sincerely yours,

P e r c e v a l L a n d o n .

5, Pall Mall Place, London.

January i st, i 9°5-

AN ACKNOWLEDGMENT.

W r i t e r s on Tibet have acquired an unenviable reputation for

concealing their indebtedness to other workers in the same field ;

I take this opportunity of saying that it would be difficult for

me to set down the full number of those to whom I am indebted

for help in writing these two volumes. Besides the authors of

all books on the subject, I am glad to think that there is hardly

a man on the expedition who, consciously or not, has not added

his tale of help to the book, and will not recognise lurking in

some phrase or footnote a fact which could only have been given