into it as by mallet strokes at every pulsation of the

heart. Partial relief is secured by a violent fit of sickness

(which, however, is not always forthcoming), and

through all this you have still to go on, to go on, to go on.

Here, too, the wind exacts its toll, and drives a cold,

aching shaft into your liver. This is no slight matter,

for the toil of climbing is excessive, and the exertion of

covering half a mile will drench a man with perspiration.

He then sits down, and this strong wind plays

upon him to his own enjoyment, and to the destruction

of his lungs.*

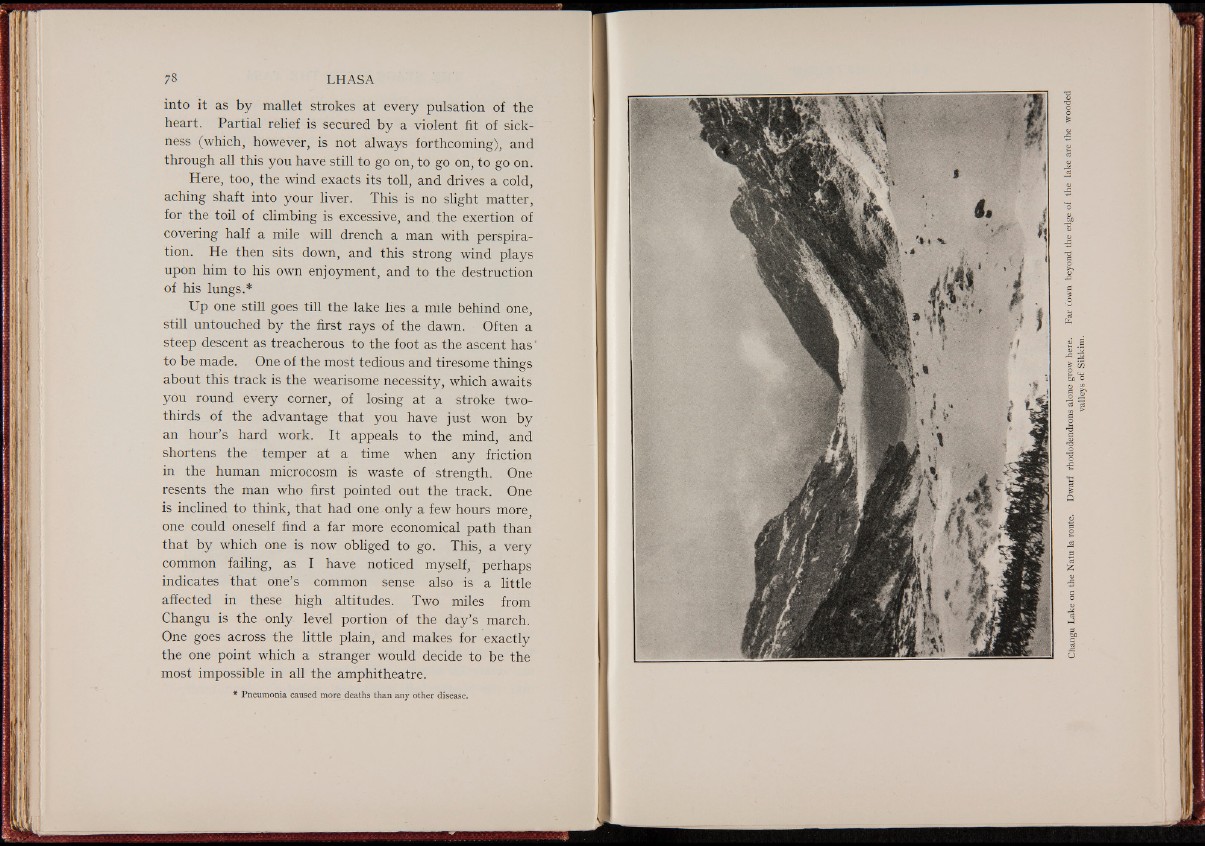

Up one still goes till the lake lies a mile behind one,

still untouched by the first rays of the dawn. Often a

steep descent as treacherous to the foot as the ascent has'

to be made. One of the most tedious and tiresome things

about this track is the wearisome necessity, which awaits

you round every corner, of losing at a stroke two-

thirds of the advantage that you have just won by

an hour’s hard work. It appeals to the mind, and

shortens the temper at a time when any friction

in the human microcosm is waste of strength. One

resents the man who first pointed out the track. One

is inclined to think, that had one only a few hours more,

one could oneself find a far more economical path than

that by which one is now obliged to go. This, a very

common failing, as I have noticed myself, perhaps

indicates that one’s common sense also is a little

affected in these high altitudes. Two miles from

Changu is the only level portion of the day’s march.

One goes across the little plain, and makes for exactly

the one point which a stranger would decide to be the

most impossible in all the amphitheatre.

* Pneumonia caused more deaths than any other disease.