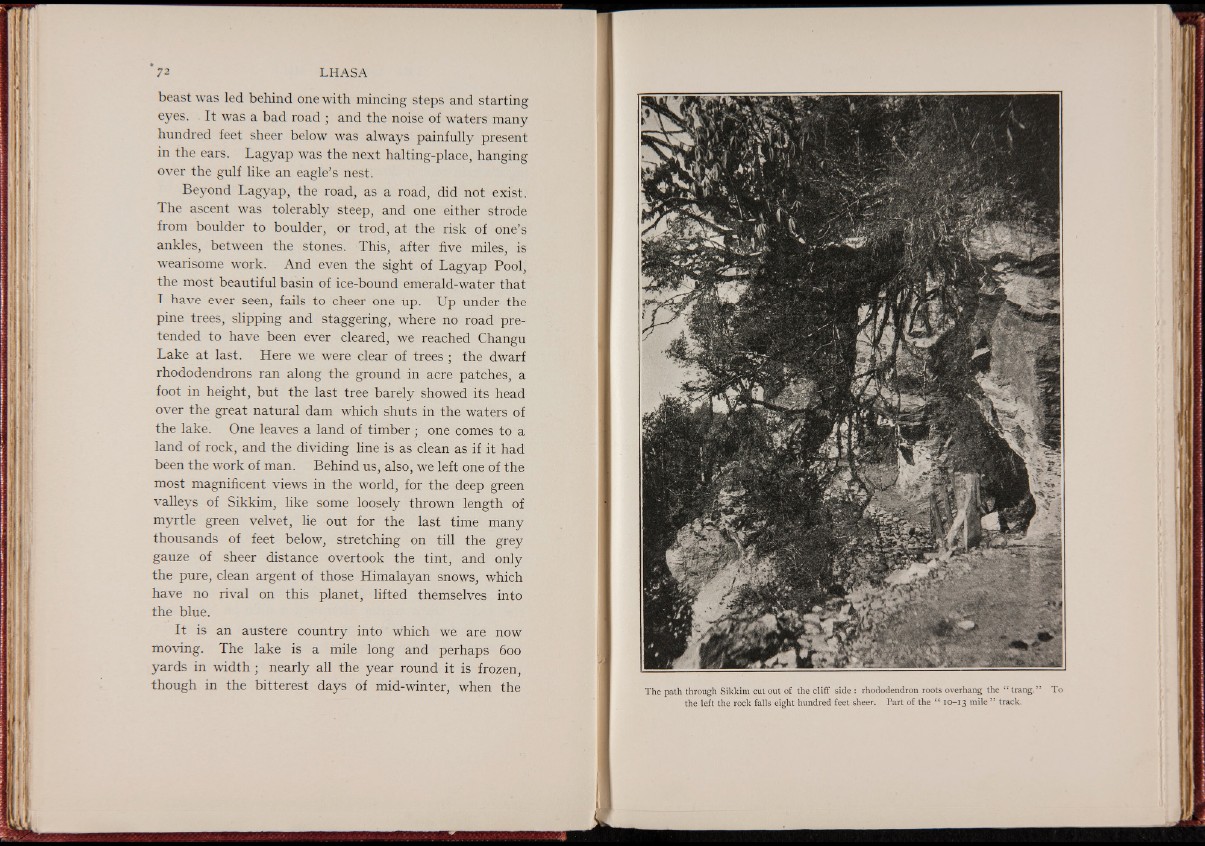

beast was led behind one with mincing steps and starting

eyes. It was a bad road ; and the noise of waters many

hundred feet sheer below was always painfully present

in the ears. Lagyap was the next halting-place, hanging

over the gulf like an eagle’s nest.

Beyond Lagyap, the road, as a road, did not exist.

The ascent was tolerably steep, and one either strode

from boulder to boulder, or trod, at the risk of one’s

ankles, between the stones. This, after five miles, is

wearisome work. And even the sight of Lagyap Pool,

the most beautiful basin of ice-bound emerald-water that

I have ever seen, fails to cheer one up. Up under the

pine trees, slipping and staggering, where no road pretended

to have been ever cleared, we reached Changu

Lake at last. Here we were clear of trees % the dwarf

rhododendrons ran along the ground in acre patches, a

foot in height, but the last tree barely showed its head

over the great natural dam which shuts in the waters of

the lake. One leaves a land of timber ; one comes to a

land of rock, and the dividing line is as clean as if it had

been the work of man. Behind us, also, we left one of the

most magnificent views in the world, for the deep green

valleys of Sikkim, like some loosely thrown length of

myrtle green velvet, he out for the last time many

thousands of feet below, stretching on till the grey

gauze of sheer distance overtook the tint, and only

the pure, clean argent of those Himalayan snows, which

have no rival on this planet, lifted themselves into

the blue.

It is an austere country into which we are now

moving. The lake is a mile long and perhaps 600

yards in width; nearly all the year round it is frozen,

though in the bitterest days of mid-winter, when the The path through Sikkim cut out of the cliff side : rhododendron roots overhang the “ trang.” To

the left the rock falls eight hundred feet sheer. Part of the “ 10-13 mile 55 track.