farious confusion of cups and bowls and lamps, there

was a narrow shelf in front of a glazed recess. I think

that there were on this shelf ten or twelve little brass

bowls full of water, but there were no butter lamps.

The sight of glass in Tibet always attracted attention ;

it was rare enough to see a piece a foot square • this glass

was five times as large, and one wondered how it had

escaped safely across the passes to this sequestered spot.

Behind it a hard-featured Buddha scowled, a very

different representation of the Master from that placid

and kindly countenance which sanctifies him still to

many not of his own creed. Under the abbot’s guidance

we visited the rooms opening out from the temple.

There was nothing of great interest, nothing to distinguish

it from twenty other gompas. We then had

tea with our host, and afterwards we asked permission

to see one of the immured monks. Without any

hesitation the abbot led the way out into the sunshine,

which lay sweltering over the spring-teeming spaces

of the valley below, and venturesome little green plants

were poking up under our feet between the crevices

into the stone footway. We climbed about forty feet,

and the abbot led us into a small courtyard which had

blank walls all round it, over which a peach-tree reared

its transparent pink and white against the sky. Almost

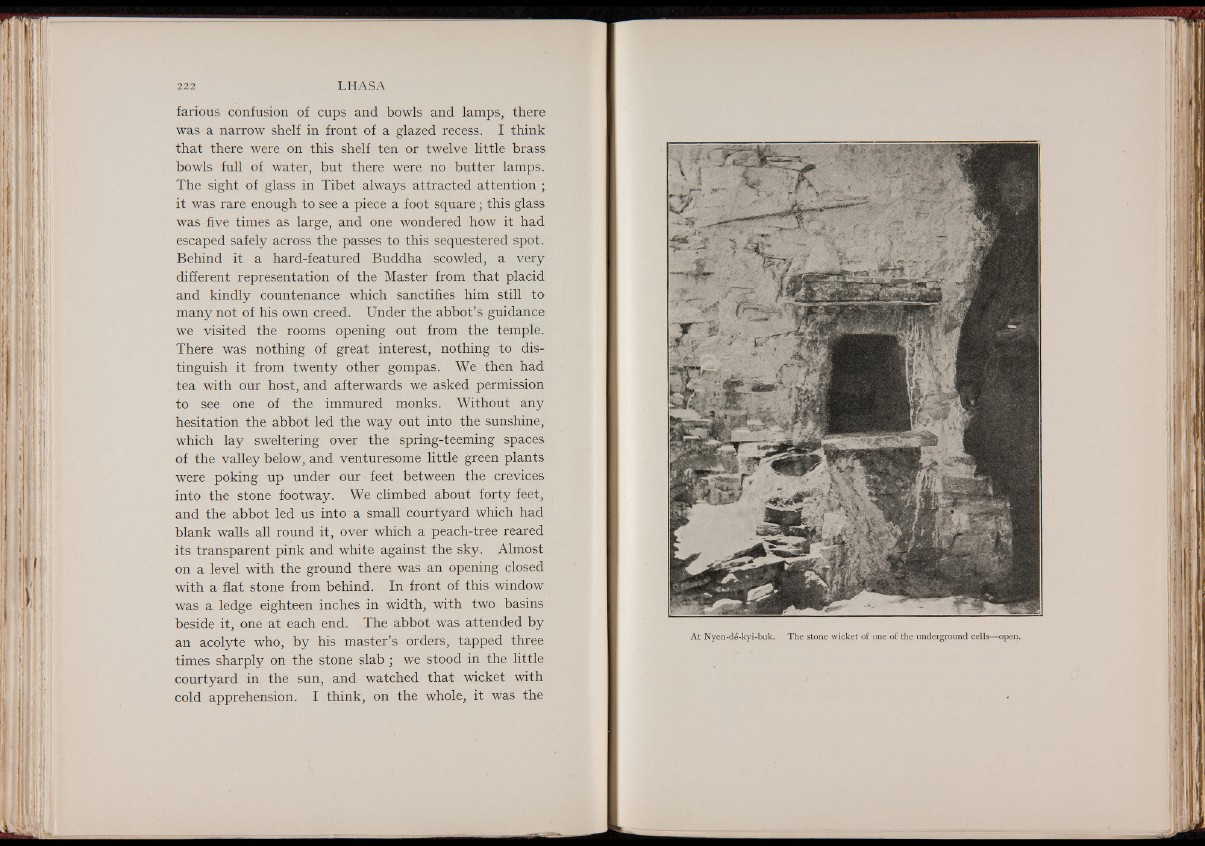

on a level with the ground there was an opening closed

with a flat stone from behind. In front of this window

was a ledge eighteen inches in width, with two basins

beside it, one at each end. The abbot was attended by

an acolyte who, by his master’s orders, tapped three

times sharply on the stone slab ; we stood in the little

courtyard in the sun, and watched that wicket with

cold apprehension. I think, on the whole, it was the

A t Nyen-dé-kyi-buk. The stone wicket of one of the underground cells— open.