to be overcome. Corduroy itself is no luxurious floor.

Your beast will like it only a little better than the quagmire

he has scrambled through. The wood is slippery,

and though the ribbing of the road prevents a long slide

it ensures a short one at almost every step.

The path on the bare mountain-side, bad as it was,

is better than that which threads the close pine trunks

of Champi-tang. Torrential rain may wash a path

away, but nothing so entirely ruins a made track as the

drip from trees. There is something about the slow

persistence that does harm which even a water-spout

could not compass. And if by this time you have any

spirit of curiosity left in you, you may notice that the

corduroy work upon the road coincides with those very

parts, which at the first blush you might consider most

protected by foliage overhead. It is getting late now

in the afternoon, and you will thank your good fortune

in having as companions unfeeling men who made

you rise at five. The worst is over, and you can stumble

along at more than two miles an hour. The hill-sides

opposite become clothed with forestry, and after an

hour or two you will find yourself before the blazing

hearth of the luxurious bungalow at Champi-tang.

On the following day, you go down to Chumbi.

You make your way along a greasy path, now passing

underneath a lonely little shrine, half hidden by the

trees, now emerging among the bared, charred trunks

of the pine army which was burnt three years ago.

Doubling the spurs again and again, you make your

way at a fairly level altitude, until a Bhutia-tent marks

the division between the official main road by the

Kag-ue monastery, and the short cut over the hills

to Chema. Down the first you elect to go. The road

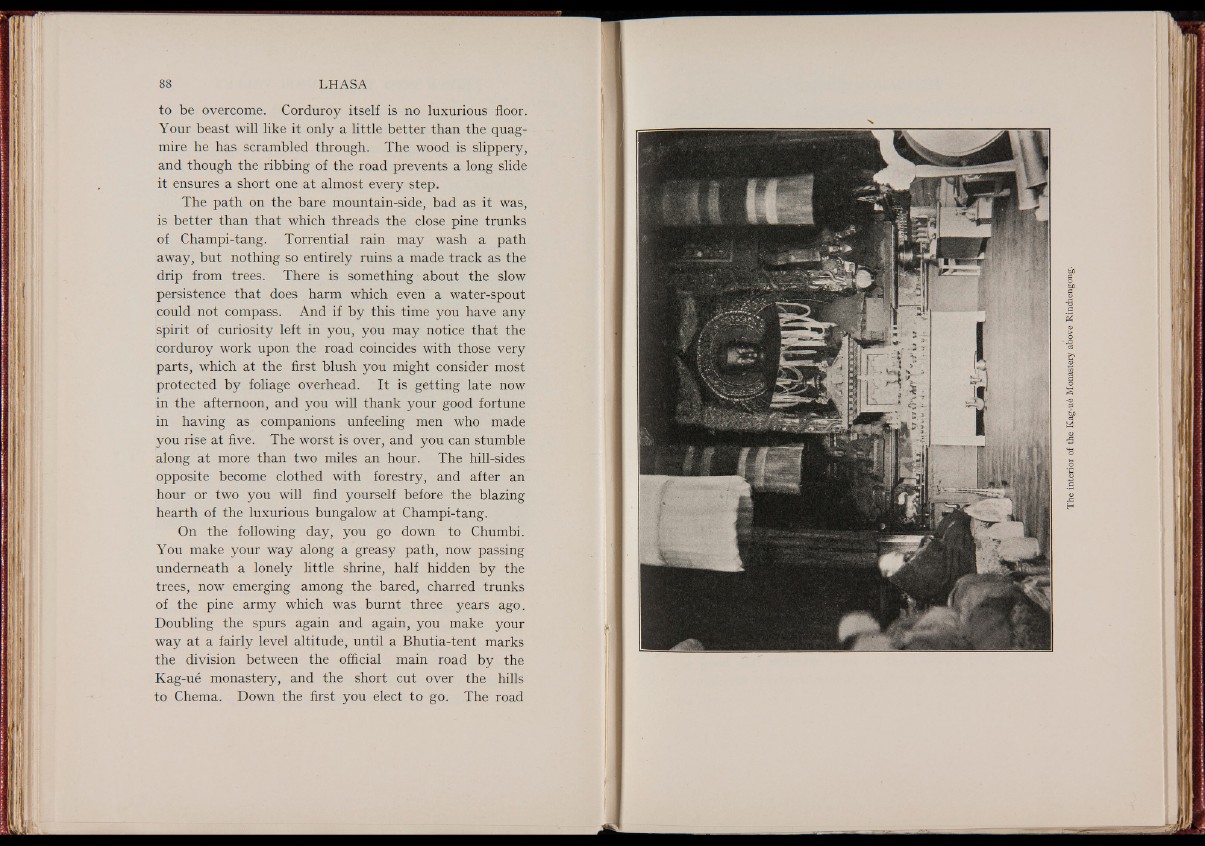

The interior of the Kag-u6 Monastery above Rinchengong.