the plains of India to that intense heaviness of both

himself and his accoutrements which, in these highlands,

is the most conspicuous sensation. I have elsewhere

referred in more detail to the physical experiences and

sufferings of the troops, and these circumstances of all

our work in Tibet should be borne in mind as an everpresent

environment, from the first climbing of the

heights of Changu or Ling-tu to the scaling of the little

ridge between Potala and Chagpo-ri.

Ra-lung is divided by a small stream into two parts.

The Tibetan village lies to the south, a mere cluster of

common adobe huts whitewashed or in ruins. On the

northern side of this affluent is the Chinese post-house,

set a hundred yards back from the edge of the river

cliff on the very spot where there is one of the curiously

marked out camping-grounds used by the two Grand

Lamas alone. The bridge over the Ra-lung chu is a

typical line of roughly-heaped stone piers, bridged across

with larger slabs of the same schistose limestone.

Crossing the river here the main road to Lhasa keeps

close beside it on the north-eastern bank for one or

two miles of a bad track. Small streams intersect its

progress, running in the wet weather in a plashy torrent

at the bottom of deep-cut ravines ; otherwise the steep

cliff wall comes down sharply on to the very path until

the last corner is turned and the broad valley of Gom-

tang is seen spreading out towards the north-west.

Here the track leaves the river-side and runs northward

over the gently sloping highlands beneath the snowy

backbone of this great spur of the Himalayas.

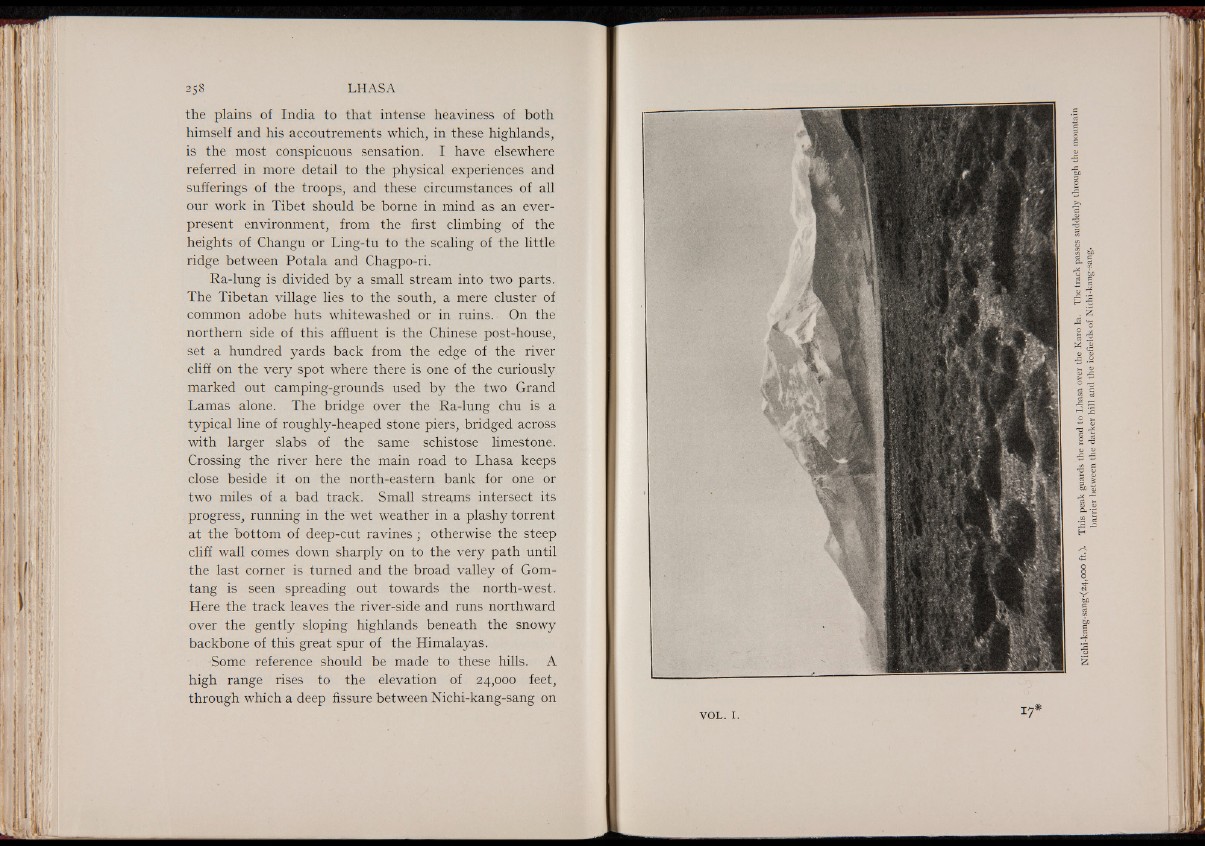

Some reference should be made to these hills. A

high range rises to the elevation of 24,000 feet,

through which a deep fissure between Nichi-kang-sang on

v o l . 1.